The Central California wildfire that Monday destroyed three homes and forced hundreds of evacuations is just the latest blaze to strain the nation’s overburdened federal firefighting system. By Monday evening, the Shirley Fire had consumed 2,600 acres near Sequoia National Forest and cost over $4 million, as more than 1,000 firefighters scrambled to contain it (it’s now 75 percent contained). Meanwhile, families on an Arizona Navajo reservation are being evacuated today in the face of an 11,000-acre blaze that as of Tuesday morning was 0 percent contained.

This year, in the midst of severe drought across the West, top wildfire managers in Washington knew they were going to break the bank, even before the fire season had really begun. In early May, officials at the U.S. Department of Agriculture (which oversees the Forest Service) and the Department of Interior announced that wildfire-fighting costs this summer are projected to run roughly $400 million over budget. Since then, wildfires on federal land have burned at least half a million acres, and the Forest Service has made plans to beef up its force of over 100 aircraft and 10,000 firefighters in preparation for what it said in a statement “is shaping up to be a catastrophic fire season.”

But the real catastrophe has been years in the making: Federal fire records and budget data show that the U.S. wildfire response system is chronically and severely underfunded, even as fires — especially the biggest “mega-fires” — grow larger and more expensive. In other words, the federal government is not keeping pace with America’s rapidly evolving wildfire landscape. This year’s projected budget shortfall is actually par for the course; in fact, since 2002, the U.S. has overspent its wildfire fighting budget every year except one — in three of those years by nearly a billion dollars.

Tim McDonnell

That sets up a vicious cycle: Excess money spent on fighting fires has to be pulled from other vital programs, including some of the very activities — clearing brush and conducting controlled burns — that are designed to keep the most destructive fires from occurring.

Jim Douglas, director of Interior’s Office of Wildland Fire, says both his agency and the Forest Service (which together are responsible for preparing for and fighting fires on federal land) are perpetually robbing Peter to pay Paul — and climate change is only making matters worse.

“It’s pretty clear that the physical environment in which we work is changing,” he says. “The underlying problem is that fire costs are increasing more often than not.”

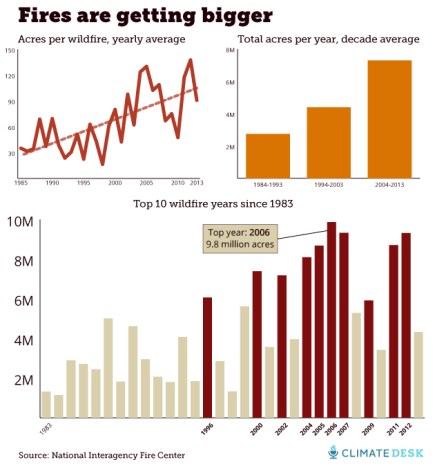

Douglas blames the rising costs on a toxic combination of urban development (“We’re spending a lot more time protecting communities and subdivisions than we did a generation ago,” he says), and a greater abundance of super-dry fuel, which leads to longer fire seasons and bigger fires. Since 1985, the size of an average fire on federal land has quadrupled, according to records kept by the National Interagency Fire Center. The total acres burned nationwide in an average year jumped from 2.7 million over the period 1984-1993, to 7.3 million in 2004-13. And of the top 10 biggest burn years on record, nine have happened since 2000.

Tim McDonnell

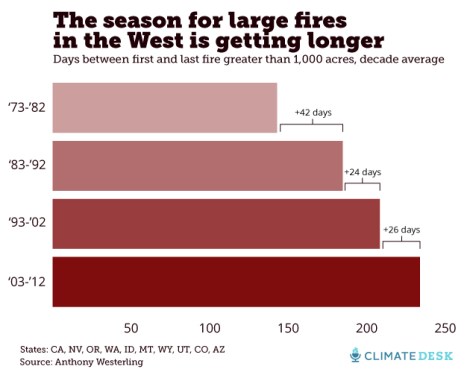

Meanwhile, dry conditions are also lengthening the season in which large fires occur, according to analysis by fire ecologist Anthony Westerling of the University of California-Merced. In 2006, Westerling counted instances of fires greater than 1,000 acres in Western states; the study, published in Science, found that “large wildfire activity increased suddenly and markedly in the mid-1980s.” Updated data provided by Westerling to Climate Desk shows that trend continued in the last decade:

Tim McDonnell

And the longer seasons mean even higher costs, explains Interior’s Douglas. That’s because seasonal firefighters must be kept on the payroll and seasonal facilities must be kept open longer.

Environmental change is complicating the work of fire managers who already had their work cut out for them restoring forests from the decades-long practice of suppressing all fires, which led to an unhealthy buildup of fuel that can turn a small fire into a mega-fire.

“Until the ’80s or so, it was easy to explain fires as consequence of fuel accumulation,” says Wally Covington, director of the Ecological Restoration Institute at Northern Arizona University. “Now, piled on that are the effects of climate change. We are seeing larger fires and more of them.”

Scientists like Covington are increasingly confident about the link between global warming and wildfires. In March, the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reported that more and bigger wildfires are expected to be among the most severe consequences of climate change in North America. And a report prepared by the Forest Service for last month’s National Climate Assessment predicts a doubling of burned area across the U.S. by mid-century.

Driving those trends are more sustained droughts that leave forests bone-dry and higher temperatures that melt snowpack earlier in the year. Both of those factors are at play this year, especially in the fire-prone West. California’s snowpack was at record lows this winter, and Covington says forest conditions across the region “are dominated by drought.”

Tim McDonnell

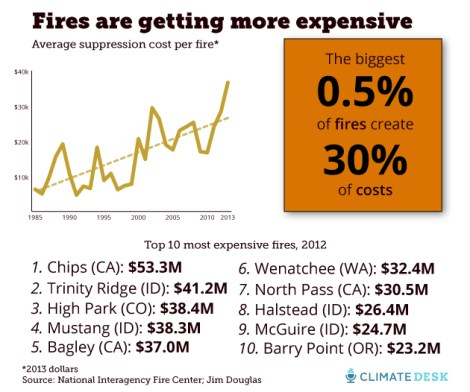

While climate conditions and urban development drive up the average cost of putting out a fire, Interior’s Douglas says his agency is still able to extinguish the majority of fires while they’re relatively small. The biggest concern, from a budgetary perspective, is the biggest 0.5 percent of fires, which according to Interior account for about 30 percent of total firefighting costs. While the average per-fire cost is now around $30,000, a handful of massive fires cost orders of magnitude more: In 2012 several dozen fires pushed into the multimillion-dollar range, with the year’s most expensive, the Chips Fire in California, reaching the stratospheric height of $53 million.

Tim McDonnell

All it takes is a few multimillion-dollar fires to drain the budget, Douglas says. Traditionally, the firefighting budget set by Congress is based on the rolling 10-year average of expenses, so that in theory the budget tracks changes in actual costs. But in practice, Douglas says, costs are rising too quickly for the budget to keep up, especially as the worst fires get worse. The result is the chronic shortfall shown in the first chart above.

In 2009, Congress attempted to patch the hole with the FLAME Act, which created a new reservoir of firefighting funds meant to “fully fund anticipated wildland fire suppression requirements in advance of fire season and prevent future borrowing” from other programs like forest management and land acquisition. Given that boost, the budget jumped into surplus the following year; but it soon dropped back into deep deficit during 2012’s devastating fire season, the third-worst in U.S. history. Last year, the situation was exacerbated by the budget sequester, which cut the Forest Service budget by 7.5 percent, eliminated 500 firefighting jobs, and left Western communities scrambling to pick up the tab.

Sen. Ron Wyden, the Oregon Democrat whose state is the second most-burned in the nation (see map above), is now pushing a new bill that he says has support from western Republicans (and, for what it’s worth, the National Rifle Association) to create an emergency fund for tackling the biggest fires that would exist outside the normal USDA/Interior budget, similar to the way FEMA currently pays for hurricane recovery. The bill is similar to a proposal by the White House, which would free up over a billion dollars in additional emergency firefighting funds.

The idea, Wyden says, is to keep officials from having to crack open the fire prevention piggy bank every time a bad fire season hits, a practice that ultimately drives up costs across the board.

“The way Washington, D.C., has fought fire in the last decade is bizarre even by Beltway standards,” Wyden says. “The bureaucracy steps in and takes a big chunk of money from the already-short prevention fund and uses it to put out the inferno, and then the problem gets worse because the prevention fund has been plundered.”

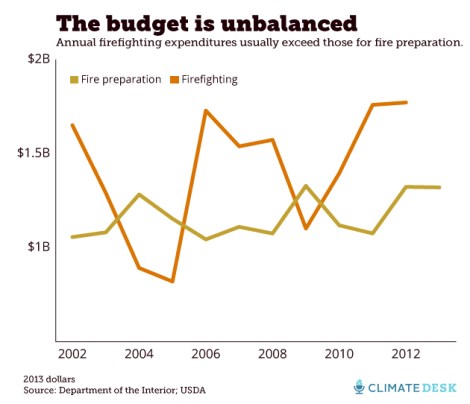

Indeed, firefighting expenditures have consistently outpaced fire preparation expenditures, even as experts like Covington and Douglas insist that, like the adage says, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. Since 2002, the average dollar spent on firefighting has been matched by only 80 cents in preparatory spending on things like clearing away hazardous fuels and putting firefighting resources in place:

Tim McDonnell

Wyden’s bill, which he calls “arguably one of the first bipartisan efforts that could make a real dent in climate change,” is still in committee, and the House version has already taken heat from fiscal conservatives like Paul Ryan (R-Wisc.). In any case, it wouldn’t take effect until next year. But Covington argues that the government needs to approach wildfires as natural disasters on par with hurricanes and earthquakes, and that we should plan for a future that is much more severe than the past.

“Earlier in the century, if they saw what’s been going on since the ’90s, it’s just inconceivable,” he says. “It alarms me that people don’t realize how much is being lost.”

This story was produced as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

This story was produced as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.