Trains — does anything else have cooler whistles? Does anything else have more impenetrable regulations?

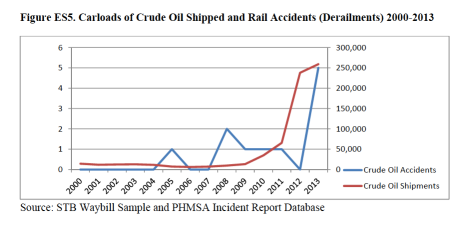

As someone whose childhood home was just a few blocks away from the freight line, I feel a personal connection to all this oil-by-rail, exploding/leaking train drama that our nation has been going through for the last two years. Just looking at this graph, I think, 2012, you were so innocent!

Last week I wrote about something that might end this disaster spike — the Department of Transportation’s (DOT) proposed new safety rules for oil-by-rail and disaster response. You could say that it took them long enough, but whatever. Let us live in the moment and be grateful they are doing this now.

But there is more. Part of the proposed rules involves the vehicle that is at the center of so much of this issue — the older-than-the-hills and puncture-prone DOT-111 tank car. These older tank cars, mostly intended for transporting non-hazardous liquids like corn syrup, have lately been drafted into ferrying volatile Bakken shale crude around the continent. Now the Transportation Department intends to phase them out. This looks like good news, and it is — but there is a wrinkle. The DOT-111s won’t be going away away. Instead, they’ll be given a new job: carrying tar sands crude from Alberta.

As Elana Schor, over at Energy & Environment Daily, writes:

DOT’s oil sands vision for older tank cars, outlined in an analysis published alongside its July 23 proposed rule, rests on the addition of thermal jackets and insulation to nearly 7,800 cars and the conversion of more than 15,000 cars to carry Canadian crude without retrofits. What the analysis leaves unaddressed, raising concerns among environmentalists, is the safety risks of filling spill-prone tank cars with crude that is less explosive but potentially more challenging to clean up.

Hell yeah, “more challenging to clean up.” Four years ago, a pipeline carrying diluted tar sands crude (aka diluted bitumen, or dilbit for short) spilled out of a pipeline and into the Kalamazoo River, and cleanup is still going on. It turns out that everything we think we know about oil spill cleanup doesn’t apply to dilbit. In the case of the Kalamazoo River, the bitumen didn’t float on the surface of the water where it could be contained and skimmed off like your more classic oil spill; instead,it separated from the solvent used to dilute it and sank to the bottom of the riverbed.

The DOT analysis assumes that the bitumen carried by the DOT-111s won’t be diluted — the word “dilbit” isn’t mentioned once. However, some tar sands crude is already being shipped by rail. Two years ago, when the State Department put TransCanada’s permit for the Keystone XL pipeline on hold, BNSF announced that the railroad was happy to start shipping tar sands crude for anyone stymied by the lack of pipeline. “Whatever people bring to us, we’re ready to haul,” a spokeswoman for the railroad told Bloomberg at the time.

According to the DOT anaylsis, BNSF expects the shipping of tar sands crude by rail to start growing in 2014 and then take off in 2016 and 2017. If you’re into that sort of thing, you can plot your own imaginary tar sands crude delivery using this neat tool from BNSF’s website.

The bitumen in a train car doesn’t have to be diluted the way that it would in a pipeline. It could just be shipped in its raw form. But if it’s loaded into a tanker car like the DOT-111, it would have to be made liquid somehow. Dilution is cheaper than the only other option: tricking out the tanker car with enough heating infrastructure to keep the cargo liquid.

These “safety vs. cost” tradeoffs play a big part in the whole crude-by-rail story. The standards are being rewritten because of accidents that have been made vastly worse because of frisky hydrocarbons in Bakken crude. It’s possible to strip that oil of its most flammable elements before it gets loaded onto a train. But doing that would have cost billions of dollars. The technology already existed in other parts of the country But there was no incentive to spend the money for it: once the crude was loaded onto a train, the liability for any accidents fell on the railroad, instead of the company that extracted it in the first place.

These new safety rules are the best chance we have right now of making sure that the risks involved in this new habit we have acquired of shipping oil around the country are shared evenly among the people who most benefit.

Is it going to be safer to use DOT-111s to ship tar sands crude than Bakken shale crude? Probably. But should we do it? Compared to shipping Bakken in a DOT-111, just about anything looks safer. That doesn’t make it a great idea.