Get ready, people. We’re about to make utility mergers sexy!

The short version: Exelon is a big, crappy utility company that’s in trouble because it’s saddled with a bunch of uneconomic nuclear plants. It wants to buy Pepco, a smaller, better utility, so Pepco’s ratepayers can help pay for those uneconomic nuclear plants. Ratepayers and activists in Pepco’s service territory — especially Washington, D.C. — rightly see this as a bad deal. Exelon has argued otherwise, but now a new independent think-tank report has pretty much destroyed the company’s case.

The long version: … hey, where are you going? Get back here. This is a hot political story, with scrappy grassroots activists fighting a corporate deal everyone said was invevitable! Also there are important lessons about contemporary electricity markets embedded in here. So stay with me. It’ll change the way you think about utility mergers!

—

Exelon is one of the biggest utility holding companies in the U.S. — “holding company” because it’s not really a utility itself so much as a company that owns a bunch of utilities. The utilities it owns mostly operate in the PJM area, on the mid-Atlantic Eastern seaboard, below New York and above North Carolina, plus parts of the Midwest. (As I explained in this post, the restructured areas of the U.S. grid are divided up into regions, each under the administration of a regional transmission organization, or RTO, that runs its wholesale power market.)

In a restructured power market like PJM’s, utilities are no longer “vertically integrated,” which is to say, they no longer own generation (power plants) and distribution (the grid). There are utilities that run distribution grids, delivering electricity to customers; they buy power from separate companies that own power plants (also sometimes confusingly called utilities). Exelon owns both: power generation, mainly in the form of Exelon Generation Company, and three distribution utilities, serving around 6.6 million people in Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Illinois.

(You may ask yourself, “If Exelon owns power generators and distribution utilities, how is it not a vertically integrated utility?” Good question! More on that later.)

Exelon Generation Company’s fleet is dominated by nuclear power — 81 percent of Exelon’s total electricity in 2013 was nuclear. As you may have heard, things are not going well for nuclear plants these days. They face competitive pressure from cheap natural gas, rising renewables, and stagnant electricity demand. Revenue from Exeleon’s nuclear fleet is declining (40 percent from pre-recession levels, by one estimate), and perhaps worse, it is unstable and unpredictable. That’s alarming for the kind of business that’s accustomed to high, steady returns.

Exelon Generation Company provides about 60 percent of Exelon’s revenue. Now that it’s going sideways, the parent company needs more stable revenue streams. And so, like many large U.S. utilities, Exelon is looking to shift resources from its merchant generators to its distribution utilities, where revenue, though smaller, is stable and predictable, because rates are established by public utility commissions (PUCs) for set periods of time.

Putting resources into regulated distribution utilities represents a kind of hedge against low wholesale power prices. Also, if wholesale power prices decline, owning distribution utilities allows holding companies like Exelon to raise rates on those customers to help cover the shortfall.

—

OK, so far so good. We know that Exelon wants more distribution utilities to shore up its sagging stock price and struggling nuke fleet.

So it has made an offer to buy Pepco Holdings, a company that owns three distribution utilities serving customers in Virginia, New Jersey, Maryland, Delaware, and the District of Columbia. In fact, Exelon has offered Pepco $6.8 billion, which, according to the aforementioned think-tank report, “represents a 20 percent mark-up over Pepco’s actual stock value just before the merger was announced, or a $1.1 billion windfall for the stockholders of Pepco. Pepco’s stock price was already inflated relative to the net book value of the assets of Pepco; Pepco’s assets are valued at only $4.3 billion.”

Offering more than $2 billion above what Pepco’s assets are worth might seem desperate — one might even suspect ulterior motives! — but Pepco’s stockholders aren’t asking questions. They love the deal, as it stands to dump giant buckets of money on their heads.

It’s not a fait accompli, though. The merger has to be approved by the PUCs of every state in which Pepco has customers (and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission). So far, it’s been approved by FERC, Virginia, and New Jersey. That leaves Delaware, D.C., and Maryland PUCs to go.

The deal would help stabilize Exelon’s revenue. It would enrich Pepco stockholders. The question before the court: Is the merger a good idea for Pepco ratepayers?

A group of consumer advocates in D.C., many now gathered under the banner of PowerDC, is arguing that it is not. You can read an excellent account of the background and the back-and-forth on UtilityDive (which by the way you should bookmark if you’re into utility geekery). As I was reading it, I have to say, every argument Exelon’s spokespeople offered in defense of the deal set off my bullshit detector.

But I’m just some schmo. Luckily, some qualified researchers have stepped in to offer deeper analysis. Their report, out of the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, argues that the merger is not in the long-term interests of D.C. ratepayers, for three reasons. (Some of the reasons also extend to Pepco ratepayers in other states, but for political reasons, the fight is focused on D.C.)

1. Exelon will inevitably raise rates on Pepco ratepayers to cover for its crap nuclear plants.

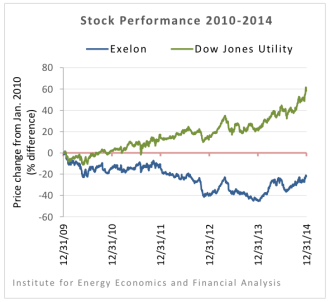

Exelon’s stock is not doing well (see chart to the right). It had to cut its dividend to stockholders by 40 percent in 2013 — the only big utility to do so between 2010 and 2013. The credit rating of its generation business has been downgraded by Moody’s. Its operating income has declined faster than the industry average.

All that — plus the enormous cash surplus it is offering to Pepco stockholders — will put enormous pressure on Exelon to get as much revenue out of Pepco as possible. And it is making no promises to the contrary:

In the proposed acquisition of Pepco, Exelon has made no promises regarding rates. Exelon has rejected a request from the District of Columbia Office of the People’s Counsel to avoid seeking a rate increase for five years after the acquisition.

Since Baltimore Gas & Electric’s parent company was bought by Exelon in 2012, its ratepayers have seen four proposed rate increases. There’s no reason to think Pepco ratepayers will escape the same fate.

2. D.C. has ambitious sustainability goals and Exelon is likely to impede them.

D.C. has big green plans. It has a renewable energy standard targeting 20 percent renewables by 2020, with 2.4 percent solar by 2023 (which would involve a huge expansion of rooftop solar). The city’s official Sustainable D.C. plan calls for 50 percent renewable energy, a 50 percent decline in energy use, and a five-fold expansion of green jobs by 2032. All those are stretch goals that will involve coordinated effort for decades.

Exelon, meanwhile, is among the worst utilities on sustainability. It opposes net metering for solar, opposes the federal tax credit for wind (which, remember, competes against its nuclear fleet), opposes various clean-energy initiatives in the Maryland state legislature, and supports guarantees and subsidies for its nuclear plants. Renewable energy reduces wholesale power prices and Exelon needs wholesale power prices to stay high to keep its nukes in business. That’s a fundamental tension that won’t go away, even if Exelon supports a few token renewable projects. (Note that every time Exelon is challenged on this, it cites the same Dunbar High School solar project — can’t it at least think of a second one?)

3. D.C. regulators would have much less control over Exelon than they do over Pepco.

Pepco hasn’t exactly been a champion of clean energy, but it has started moving in the right direction, pushed along by D.C., which represents a substantial chunk of its rate base. The D.C. PUC can impose penalties on Pepco that matter to the company.

But D.C. will represent a comparatively tiny chunk of Exelon’s rate base. D.C. consumer advocates and the D.C. PUC will have much less influence on the company’s overall direction than they do on Pepco. Exelon’s sheer size and complexity make it difficult for individual PUCs to even understand, much less effectively influence. There are several examples of big holding companies swallowing small ones and making subsequent hell for regulators (see the report for details).

—

Exelon has counter-arguments, of course. They just aren’t very convincing.

It has promised to keep employment at Pepco at least steady for two years, but it’s promised nothing after that. It has made commitments regarding reliability, but less than what D.C. law already requires. It has offered a “Customer Investment Fund” — i.e., a payoff to Pepco ratepayers — that would amount to a one-time bill credit of about $53 per customer (small beans relative to the bounty awaiting Pepco shareholders), but that’s unlikely to offset long-term rate increases.

And finally, it has promised to “ring fence” Pepco, which would allegedly protect the smaller company from any raid on its resources by the Exelon parent company. According to IEEFA, “no independent assessment of the ring fencing provisions has been made and no opinion by an independent party offered as to their integrity and ability to handle a hostile attack.” Plus the ring-fence provisions wouldn’t protect Pepco ratepayers from rate hikes, which, remember, Exelon has conspicuously not promised to avoid.

—

Pepco ratepayers can submit comments until the end of March. The whole thing will be over and decided by April 1.

—

OK, I’ve probably tested your patience enough, but let’s take a quick step back and look at some larger trends/lessons in this battle. I’ll just pick two.

One, electricity restructuring (which I discussed in my wildly popular cult classic utility series) was supposed to make power markets more competitive, by breaking apart power generation and distribution and having power generators battle it out in an open wholesale power market. And it did, to some extent.

But remember that question you asked earlier, about why Exelon itself doesn’t count as a vertically integrated utility? That was a good question! Exelon owns a bunch of nuclear plants and a bunch of distribution utilities. It thus has a built-in conflict of interest: It has every incentive to use the latter to pay for the former. Why is that legal?

It wasn’t always. The Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 prohibited that sort of thing. Here’s what PUHCA did, according to a primer from Public Citizen:

(1) limits the geographic spread (therefore, size) of utility holding companies, the kinds of business they may enter, the number of holding companies over a utility in a corporate heirarchy, and their capital structure; (2) controls the amount of debt (thus, cost of capital), dividends, loans and guarantees based on utility subsidiaries (so the parents can’t loot or bankrupt the utility subsidiary), and the securities that parent companies may issue; (3) regulates self-dealing among affiliate companies and cross-subsidies of unregulated businesses by regulated businesses; (4) controls acquisitions of other utilities and other businesses; and, (5) limits common ownership of both electric and natural gas utilities.

(Interestingly, FDR wanted to ban holding companies from owning public utilities at all — PUHCA was the compromise.)

Naturally, utility holding companies didn’t like this and in 2005 they persuaded a Republican Congress to repeal it, via the Energy Policy Act of 2005. Since then, the predicted consolidation in the utility industry has taken place right on schedule. Now the landscape is dominated by huge companies like Exelon that have these conflicts of interest baked in. FERC is supposed to apply extra scrutiny to “affiliate transactions” — i.e., a holding company’s various utilities selling power to one another — but that can’t fully counteract the built-in business-model tensions and the power these huge companies have over regulators.

Utility holding companies eating small distribution utilities is, in short, a lamentable trend that’s likely to stymie the greening of the U.S. power system. Occupy PUCs!

Second, what’s happening to Exelon is not unusual. As electricity demand stays flat, renewables get cheaper, and natural gas continues to flood the market, companies saddled with big, slow baseload plants, mainly coal and nuclear, are struggling. This trend is only going to accelerate, and as it does, these companies — which, remember, are getting bigger and more powerful — are going to be looking for any way possible to saddle taxpayers or ratepayers with the costs of propping up their share price. Expect the battle between Exelon and D.C. consumer advocates to replay itself many times over in coming years.