Just two years ago, Lake Oroville was so dry that submerged archaeological artifacts were starting to resurface. That was in the middle of California’s epic drought — the worst in more than a millennium.

And then the rains came. This winter is on track to become Northern California’s soggiest on record. A key precipitation index is running more than a month ahead of the previous record pace, set in the winter of 1982–1983 (records go back to 1895). Lake Oroville is so full that it spilled over for the first time, spurring evacuations downstream.

California’s climate has always been extreme (even before humans got seriously involved), but what’s happening right now is just ridiculous. We are witnessing the effects of climate change play out, in real time.

Lake Oroville is as full as it has ever been, and remains vulnerable: We’re still in the peak of the rainy season, and more rain is on the way. On Tuesday and Wednesday, crews at the beleaguered dam worked around the clock to stabilize and reinforce the emergency spillway in anticipation of a fresh torrent of rainfall. But the scale of action — truck after truck of giant boulders dumping 1,200 tons of rock per hour — was small in comparison to the immense scale of erosion that has already taken place. There’s a real risk that the lake could spill over the top a second time.

And it’s not just Oroville. Major reservoirs ring the Central Valley, and nearly every one is full, or nearly so, as the Sacramento Bee reported earlier this week. Several levees statewide are seeping, and workers intentionally breached one along the Mokelumne River in Northern California over the weekend to relieve pressure. The levee system was simply not designed to be this stressed for extended periods of time.

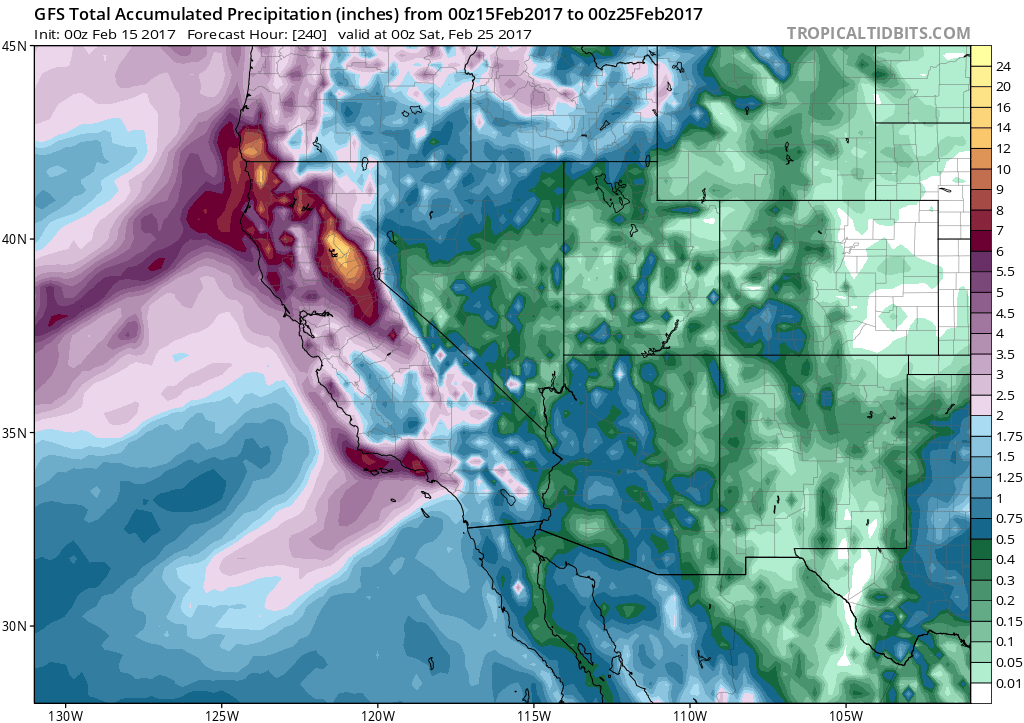

Five successive waves of storms in the coming week could bring another foot of rainfall. The graphic below shows the amount of rain (and liquid-equivalent snow) on the way over the next seven days — enough to prompt renewed warnings from the National Weather Service.

NOAA/GFS model/Tropicaltidbits.com

Climate science and basic physics suggest we are already seeing a shift in the delicate rainfall patterns of the West Coast. A key to understanding how California’s rainy season is changing lies in understanding what meteorologists call “atmospheric rivers,” thin, intense ribbons of moisture that stream northeastward from the tropical Pacific Ocean and provide California with up to half of its annual rainfall. Exactly how atmospheric rivers will change depends on greenhouse gas emissions and science that’s still being worked out.

Atmospheric rivers are already responsible for roughly 80 percent of California’s flooding events — including the one at Lake Oroville — and there’s reason to believe they are changing in character. Since warmer air can hold more water vapor, atmospheric rivers in a warming climate are expected to become more intense, bringing perhaps a doubling or tripling in frequency of heavy downpours. What’s more, as temperatures increase, more moisture will fall as rain instead of snow, increasing the pressure on dams and waterways during the peak of the rainy season. There’s even new evidence that especially warm atmospheric rivers can erode away existing snowpack.

Peter Gleick, chief scientist of the Pacific Institute and frequent visitor to the Oroville area, is clear about what the drama at Oroville represents. “We’re seeing evidence of more extremes,” he says. “To ignore that would be a mistake.”

We’ve built dams based on old weather patterns, not for the extremes we’re now seeing. A clear problem emerges when we manage society for how things were, not how things are. In many ways, we are planning for the future with the expectation that the weather will be more or less the same as in the past. It won’t be.

The acting director of the California Department of Water Resources, Bill Croyle, made a telling statement earlier this week when asked why the infrastructure at Oroville seemed so fragile. “I’m not sure anything went wrong,” Croyle said. “This was a new, never-happened-before event.”

If we don’t start imagining and preparing for more “new, never-happened-before events,” more people will be put in danger — like they are right now in Oroville.

The near-disaster at Oroville has prompted another broad discussion about our country’s decrepit infrastructure, which arrives in the context of the Trump Administration’s plans to boost infrastructure spending.

But this is about more than just spending money to fix up our aging dams. The entirety of our country’s infrastructure needs to be reevaluated with the understanding that we have a unique opportunity to reimagine our shared future. If things are rapidly changing anyway, we might as well build a future consistent with our new weather reality.

At a place like Lake Oroville, that might mean leaving more space in the reservoir for flooding than has been done in the past. That wouldn’t be popular, because it would reduce the reservoir’s capacity, even as rising temperatures spur demand for more water. It may also mean increased resources for counseling services in coastal and riverine communities, as flooding events become more frequent and families consider whether to relocate. The state is already on a good start: Earlier this week, the California Department of Water Resources released a draft resolution for a comprehensive response to climate change, including dam operation.

After the current storms pass, California will still have two months left in its rainy season. It seems likely that 2016–2017 will become the wettest rainy season in state history. That means the danger at Lake Oroville won’t completely pass until this summer.

“They’re going to have to run the main spillway all spring in order to prevent additional flooding,” Gleick said. “I think people are going to be a little nervous for the next few months.”