Brazil’s economy is teetering on the edge of collapse. The country’s political regime has been rocked by recent corruption scandals, and impeachment proceedings are encircling the nation’s leaders. And yet things couldn’t be much better for Brazil’s soybean farmers.

At the beginning of the last decade, Brazil emerged as a major soybean exporter. Today, Brazil produces about one-third of the global supply and earns more from soybean exports than from any other commodity.

Although soybean production is generating revenues for Brazil, it could spell trouble for the nation’s widely lauded environmental commitments.

Brazil is the first emerging economy that has pledged to make absolute reductions in its greenhouse gas emissions – that is, reductions from the level that it emitted at a specific point in time (2005), not from an estimate of what it will emit at some future time. Its climate plan calls for cutting emissions by more than 40 percent by 2030, with most of its emission reductions to come through avoiding deforestation. By 2030, Brazil has pledged to restore 12 million hectares of carbon-absorbing forest and eliminate illegal deforestation.

As social science researchers who study environmental change in the Amazon and the Brazilian savanna known as the Cerrado, we have seen the country’s agricultural sector grow rapidly in once-marginal regions. We believe that over the next several years, with Brazil’s soybean sector thriving and its political establishment in crisis, the nation’s commitment to slowing climate change will be severely tested.

Why economic downturns are good for soy farmers

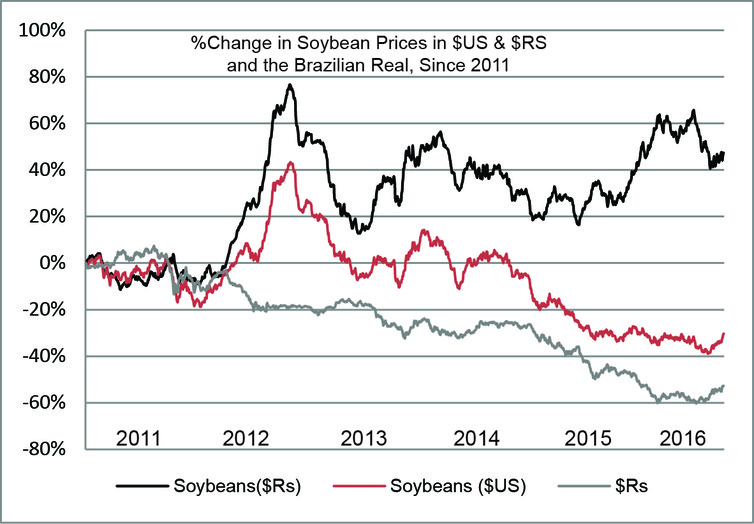

Tough economic times for Brazil can mean boom times for soybean farmers. Soybean prices in Brazil generally depend on two factors: the global price for soybeans, and the value of the local currency (the real) against the U.S. dollar.

Obviously, a high global price for soybeans means more money for farms. However, the importance of the local currency is even more critical for farmers’ bottom lines. Commodities like soybeans are priced in dollars but purchased in local currency, so when the Brazilian real is weak, farmers receive more value (in local terms) for their harvest and earn higher profits.

This dynamic creates a paradoxical relationship between Brazil’s agriculture sector and the national economy: When the economy struggles, farmers reap big profits. In the early 2000s, when the real fell to one-third of its value over a three-year period, soybean profits jumped to stratospheric levels.

In response, farmers converted an area equivalent to the size of Indiana to soybean production. In some areas cropland prices nearly tripled.

Brazil’s current economic collapse is once again creating windfall conditions for soybean farmers. Over the past year and a half, the cracks in the country’s economy have become rifts and the real has lost more than one-third of its value. The further the currency falls, the higher soybean prices rise. From 2011 to 2016, soybean prices increased by 70 percent, peaking in January 2016.

Percent change in soybean prices, and the value of Brazil’s currency, since 2011. Soybean prices in Brazil have surged to near-record levels, even as prices, in terms of U.S. dollars, have declined.ESALQ/USP

In local terms, we estimate that the value of this year’s harvest will be more than one-third larger than the harvest just two years ago. The U.S. Department of Agriculture projects that this year Brazil will produce nearly as many soybeans as the United States, an output that was unthinkable even just a few years ago.

Soybeans are generating valuable foreign exchange, new investment capital and high-wage jobs, all of which Brazil critically needs. As the farm sector’s economic clout increases, so does its political influence. Earlier this year during Carnival celebrations in Rio de Janeiro, in a procession seemingly transplanted from a U.S. state fair, dancers dressed as cotton, corn and soybeans paraded through the streets and were “harvested” by a giant float in the shape of an agricultural combine.

[protected-iframe id=”9a8f1f61b3d6f59011ff7b7026f9e871-5104299-94886244″ info=”https://player.vimeo.com/video/154817690″ width=”660″ height=”371″ frameborder=”0″ webkitallowfullscreen=”” mozallowfullscreen=”” allowfullscreen=””]

Brazil’s agriculture lobby is gaining ground as President Dilma Roussef’s Partido dos Trabalhadores (Workers Party) disintegrates in a wave of corruption scandals. We believe government support for enacting new environmental regulations and enforcing existing environmental laws is already fading.

Forests at risk

After the international community and Brazil’s domestic environmental groups denounced large-scale deforestation in the Amazon in the early 2000s, the government adopted a battery of reforms to reduce forest losses.

Enormous new forest reserves were created and indigenous reserves were expanded. New environmental regulations were enacted to inhibit clearings for cattle pastures and soybean farms. Private agribusinesses worked with environmental advocacy groups, intervening in the soybean and cattle supply chains to discourage land clearing, especially for soybean production.

Evidence suggests that these measures worked. Deforestation fell from nearly 30,000 square kilometers in 2004 to less than 5,000 square kilometers in 2012. But next year the incentive to clear land will be greater than it has been in a decade. Windfall profits from this year’s soybean harvest will give landowners both the incentive to purchase or clear land and the capital that they need to do so.

Early signs of a new wave of deforestation in the Amazon are already appearing. Late last year the Brazilian government released data that showed a 16 percent increase in tree destruction over 2014 levels. The largest increases in forest loss were recorded in Brazil’s leading soybean-producing state, Mato Grosso.

The next several years could well pose a breaking point for Brazil’s economy, which currently is being held together by the country’s booming agriculture sector. In turn, further expansion of agriculture could derail Brazil’s climate commitments.

For most of this decade Brazil has received tremendous acclaim for its environmental actions. Brazil also stands ready to sign the climate change agreement negotiated late last year in Paris. But the country’s ability and will to follow through on those commitments has never been in such doubt.![]()