This story is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

At last week’s Conservative Political Action Conference, GOP chair Reince Priebus had some strong words about how President Barack Obama prioritizes threats to national security.

“Democrats tell us they understand the world, but then they call climate change, not radical Islamic terrorism, the greatest threat to national security,” he said. “Look, I think we all care about our planet, but melting icebergs aren’t beheading Christians in the Middle East.”

The comment came after the president, in a lengthy interview with Vox, said that the media often overplays the danger of terrorism relative to climate change. It’s not the first time Obama has made a point along those lines. In his State of the Union address in January, he said that “no challenge poses a greater threat to future generations” than climate change. A few weeks later, in his 2015 national security strategy, the president referred to global warming as an “urgent and growing threat” to national security.

But while Priebus’ jab earned him a hearty round of applause at CPAC, new research indicates that his iceberg comment doesn’t hold water.

For the last couple years, Middle East experts have pointed to the ongoing civil war in Syria as a prime example of how climate change can contribute to violent conflict. The country’s worst drought on record arrived just as widespread outrage with President Bashar al-Assad’s dictatorial regime was reaching critical mass; as crops failed, an estimated 1.5 million people were driven off rural farms and into cities. While grievances with the Assad regime are many, from economic stagnation to violent crackdowns on protesters, the impacts of the drought were likely the final straw.

The narrative in Syria fit perfectly with what many top military leaders, including at the Pentagon, were beginning to project: In parts of the world where tensions are already high, the impacts of natural disasters and competition for resources are increasingly likely to ignite violence. A 2013 study by analysts at Princeton found that in some parts of the world, global warming could lead to a 50 percent increase in conflict by mid-century.

But in Syria, there was some uncertainty about whether that drought in particular was a product of human-made climate change. In other words, is the climate-driven conflict there merely representative of what might happen more often in the future, or is it an actual consequence of burning fossil fuels?

An answer to that question was published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Colin Kelley, a geographer at the University of California-Santa Barbara, found that a multiyear drought as severe as the one that hit Syria from 2007 to 2010 was made two to three times more likely because of climate change, compared to natural variability alone.

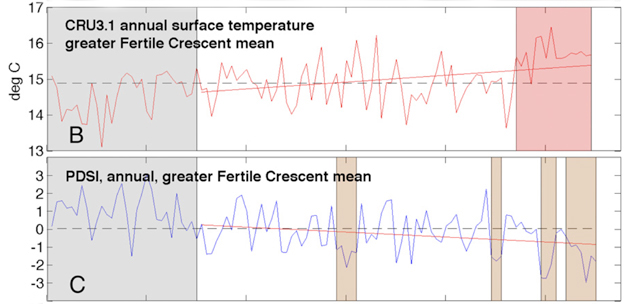

The study is the first to examine a century’s worth of precipitation and temperature data for the Fertile Crescent (the lush region surrounding the Tigris and Euphrates rivers that was hit hardest by the drought) for clues about a possible human fingerprint on the recent drought. Sure enough, the data shows that “three of the four most severe multiyear droughts have occurred in the last 25 years, the period during which external anthropogenic forcing has seen its largest increase.” Here’s the relevant data from the study:

Kelley et al, PNAS 2015

The lines in both charts proceed chronologically, starting at 1900, with a tick mark every 20 years. In the top chart, a regional warming trend is clearly visible, with the red box highlighting the recent period where temperatures were consistently above the long-term average. The bottom chart shows the Palmer Drought Severity Index, a standard metric for measuring drought in agricultural areas that combines temperature, precipitation, and soil moisture data (lower numbers are more severe). The brown boxes show droughts (where the PDSI is below the long-term trend) of at least three years.

The study also includes data from a model that compared two sets of projected temperatures in the Fertile Crescent, one with greenhouse gas influence and one without. The observed record matches closely with the greenhouse gas model, suggesting that climate change played a critical role in shaping conditions in the region.

“The bottom line is, what we’re trying to show is that these trends are due to the climate change signal,” Kelley said of the charts above. “There’s no natural signal for that.”

In other words, Kelley said, there’s a clear line of causation from human-caused greenhouse gas emissions to the deaths of 200,000 Syrians in the civil war.

With that said, Kelley added that there are a number of other factors at play here. The impact of the most recent drought was made worse by the fact that it came on the heels of two other severe droughts, so groundwater supplies were already low and farmers already struggling. Moreover, Assad’s predecessor and father, Hafez al-Assad, instituted a system of agricultural policies that encouraged farming in water-scarce areas, setting farmers there up to be highly vulnerable to future drought. And it’s impossible to know how the drought would have affected the political climate in the absence of Assad’s other unpopular practices; it’s possible that a more stable government would have been able to better weather the drought.

Still, the study carries important implications for the future of the region, said Francesco Femia, co-director of the Center for Climate and Security. The climate trends highlighted in this study indicate that replacing Assad won’t be enough to secure stability in the region.

“If or when the conflict in Syria comes to an end, will its farmers and herders be able to regain their livelihoods?” Femia said. “Given the continued instability and a forecast of increased drying in the region, this issue should be better integrated into the international security agenda.”