350.org volunteer Mark Schwaller on Tuesday before the Radiohead show. (Photo by Sam Parker.)

The amphitheater formerly known as Great Woods, at the edge of a large conservation area in Mansfield, Mass., is now called the Comcast Center. Given that the headliner there on Tuesday night was Radiohead — a band that famously dropped its major corporate label, once touted Naomi Klein’s No Logo, and is now teaming up with the grassroots climate activists of 350.org — the name dripped a fitting irony.

Not that Radiohead has ever had a problem with contradiction or cognitive dissonance. Arty, cerebral darlings of serious post-boomer, meta-critical rock, they’ve made a career and some pretty great music out of it — doing their best to subvert techno-consumer culture by its own devices for a good two decades.

So whatever else I may have felt, as a longtime Radiohead listener meeting up with a dozen fellow 350.org volunteers at the Comcast Center to help recruit concert-goers for the climate fight, the ironic dissonance of the setting made a certain sense. I mean, you have to admit: There’s something slightly dissonant about Radiohead as mood music for the climate movement. The band’s vibe — ethereal but intense, more than a little dark at times, even manic-depressive — may match many a climate activist’s state of mind more often than we’d like to admit. But it’s hardly an obvious fit with the bright, “Yes we can!” spirit of a 350 rally. Which is to say, don’t worry: There’s nothing wrong with you, you’re not missing some subtle coded message, if the 350 logo doesn’t pop into your head when you hear Thom Yorke sing.

But this leg of Radiohead’s King of Limbs tour — Tuesday’s concert was the first of at least 10 U.S. shows where 350 has been given prime real estate to set up its tent and make its pitch — may begin to change that. And I hope it does, for more reasons than may be obvious.

To begin with, it has to be said: The music industry, and the big-bucks live-music industry in particular, is a pretty good symbol of a civilization barreling its way toward the brink of climate catastrophe. The mega-wattage, the fossil-fueled mileage (both band’s and audience’s), the concessions and merchandise, the sheer size of a single large concert’s carbon footprint (despite any offsets or green LEDs) — all for a few fleeting hours of escape, the communal contact hit that only a mass of human bodies moving to the same beat, staring at the same light show, can deliver. And then the spectacle rolls (or flies) on.

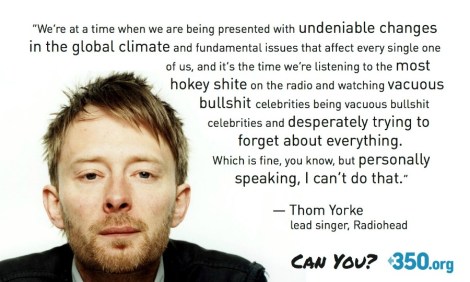

The guys in Radiohead are fully conscious of all this, of course. They’re nothing if not self-aware. And even as they’ve ventured now and then into political causes, they’ve avoided the kind of outsized (if sincere) do-goodism of some other rock stars. So when Stephen Colbert put the topic of climate change to Yorke and guitarist Ed O’Brien last fall, mischievously noting the fossil-fuel dependence of what they do (“Did you guys come here on an oxcart? … Are you living an oil-free lifestyle?”), they played it cool and didn’t take the bait or try to rationalize (though they have made real efforts to lower their tours’ footprint). Yorke talked about oil-industry campaign funding instead. Smart man, on message. He knows the climate fight isn’t simply about personal or corporate responsibility, it’s about large-scale politics.

Which shouldn’t be surprising. He’s not exactly a rookie. Yorke joined with Friends of the Earth in 2005 to help launch The Big Ask, the U.K. political campaign aimed at carbon emissions. In 2009, he went to Copenhagen. In 2010, he teamed up for the first time with 350.org on its 350 EARTH “global art project,” bringing more than 1,000 people together in Brighton to create an image of King Canute on the beach (he who attempted to hold back the tide). Now he’s bringing 350 on tour.

“Every successful movement has had music,” 350’s Jamie Henn says in an email, “and the climate movement is no different. We couldn’t be more excited for Radiohead to be providing part of the soundtrack.”

So, what about that part of the soundtrack? There’s still the question of the aesthetic and the mood of the music, and what it signifies.

Much, much (too much?) has been written about Radiohead’s music, and I make no claim to originality here. I’ve been drawn back recently to the astute, classical- and jazz-informed take on the band by The New Yorker‘s Alex Ross in a long (and brilliant) 2001 profile and to a brainy 2006 essay by Mark Greif, titled “Radiohead, Or the Philosophy of Pop,” in the Brooklyn-based journal n+1. To be sure, all the analysis can get tiring. “Really, we don’t want people twiddling their goatees over our stuff,” drummer Phil Selway told Ross. “What we do is pure escapism.” Or as Yorke added: “We’re fallible, this is fallible … We want to kind of mellow it all out a bit. Just chill the fuck out.”

Easier said than done, mates. In his essay, Greif pinpoints “the first notable quality” of Radiohead’s music: “the evocation … of unending low-level fear.” He goes on:

The dread in the songs is so detailed and so pervasive that it seems built into each line of lyrics and into the black or starry sky of music that domes it. It is environing fear, not antagonism emanating from a single object or authority. It is atmospheric rather than explosive …

Meanwhile, in the lyrics, and “in the musical counterpoint of chimes, strings, lullaby,” Greif hears “a desperate wish for small, safe spaces” — for “sanctuary.” But, he adds, “when the songs try to defend the small and safe, the effort comes hand-in-hand with grandiose assertions of power and violence,” as though from out of “our dread-filled contemporary universe.” And he quotes (from OK Computer‘s “Karma Police“):

This is what you get,

this is what you get,

this is what you get,

when you mess with us.

An atmospheric dread. A desperate wish for sanctuary. Power and violence of the contemporary universe (This is what you get when you mess with Mother Nature!). Step right up. “It is the 21st century,” York sings on “Bodysnatchers” (from 2007’s In Rainbows).

But soundtrack for the climate movement? Radiohead is what we listen to in our private, introspective, not to say despairing, moments — “alone, with earphones on,” as one young 350 volunteer named Jessica said to me. She has a hard time hearing it as pump-up music for a climate rally. There at the Comcast Center before the show, holding clever signs (“Karbon Police”) and making earnest, upbeat conversation with concertgoers who drifted over, I knew what she meant.

And yet, the more I think about it, maybe the climate movement can stand to take on a little more of the stark, honest emotion found in Radiohead’s songs. And I don’t just mean in private, with earphones on; I mean out in the open and into the mix.

Because it seems to me, as well as to a lot of climate activists I know, that we’ve reached the point where intellectual honesty about climate change requires not only an understanding of what science is telling us, but just as much, a kind of emotional honesty about the situation we’re in — about what a world of greater than 2 degrees C warming this century will likely mean. It may also require embracing the contradictions that arise when you build a truly broad-based, mass movement that transcends old categories (“environmentalism,” “conservation”) and ideological orthodoxies — and that uses the tools and arts of the techno-consumer culture to subvert and transform the culture from within.

OK, so you still don’t think Radiohead and the climate movement go together? You’re right. They don’t. Which is what might make them a paradoxically perfect fit for this dread-filled, dissonant moment of ours.

Radiohead closed the show on Tuesday night with the scarily beautiful “Reckoner” from In Rainbows. Call it mood music for a moment of reckoning, but with more grace and beauty than dread.

Reckoner

You can’t take it with you

Dancing for your pleasure …Reckoner

Take me with you

Dedicated to all you

All human beings

“Something about Radiohead inspires a disorienting kind of hope,” Ross wrote in 2001. Something about that assessment still rings true.