This story was originally published by Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Earthquakes are synonymous with California to most Americans, but West Coasters might be surprised to learn they’re far from the new center of the seismic landscape in the United States.

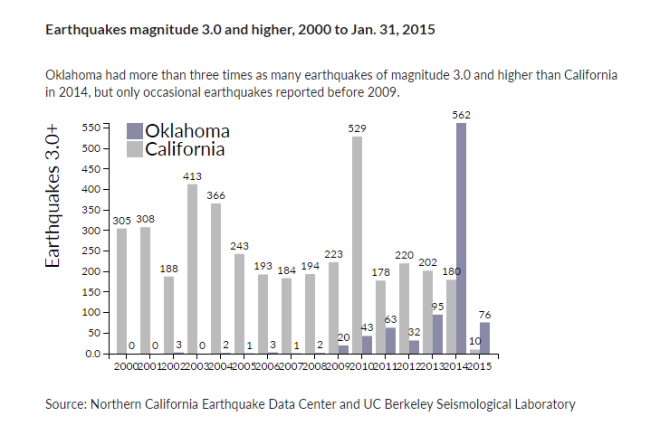

Oklahoma recorded more than three times as many earthquakes as California in 2014 and remains well ahead in 2015. Data from the U.S. Geological Survey shows that Oklahoma had 562 earthquakes of magnitude 3.0 or greater in 2014; California had 180. As of Jan. 31, Oklahoma recorded 76 earthquakes of that magnitude, compared with California’s 10.

According to the Advanced National Seismic System global catalog, in 2014, Oklahoma even beat Alaska, the nation’s perennial leader in total earthquakes, though many small events in remote areas go unrecorded there.

In California, earthquakes always have been relatively common, but in Oklahoma, they were much more rare — at least until 2009.

And though Oklahoma has had the most dramatic increase in earthquakes, other states such as Kansas, Texas, Ohio, and Colorado also are seeing more “induced seismicity” — earthquakes likely triggered by human activity.

So far, earthquakes have proven much more deadly on the West Coast. In California, 63 people were killed in the 1989 Loma Prieta quake, and about 60 died during the Northridge event in 1994. None of the recent Midwest quakes have resulted in deaths. But the changes in the Midwest are so significant that the country’s top experts are being forced to fundamentally rethink their approach to seismic risk.

“A fundamental assumption of the old maps was that everything stays the same. Now we’re challenged with the earthquakes rates varying with time,” said William Ellsworth, a seismologist for the U.S. Geological Survey who is part of a group studying new ways to understand the hazards of induced earthquakes. “Everybody realized that this was an appropriate thing to do because they didn’t know what to do.”

Numerous studies agree that wastewater disposal from hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, is a major factor in increasing seismic activity.

Massive amounts of water, along with other fluids, are used in the fracking process to break rocks, release natural gas and push it to the surface. That water, along with brine pulled from those rocks, comes back to the surface and has to go somewhere. So drillers inject it into underground disposal wells. In Oklahoma, more than 50 billion gallons of wastewater went into disposal wells in 2013 alone, according to the Oklahoma Geological Survey. The fracking process itself also has been linked to earthquakes, though those generally have been smaller than those associated with wastewater disposal.

The areas facing new earthquakes share a significant burst of drilling activity and pre-existing geologic faults. Heavily drilled areas such as North Dakota’s Bakken formation, which aren’t located near faults, have not seen the same increase in earthquakes.

The largest Midwest quake in recent years — a magnitude 5.7 — was centered near Prague, Okla., on Nov. 5, 2011. The city of 2,400 people is about two miles east of the Wilzetta fault system, and in 2011, it had several active wastewater disposal wells nearby.

A 2013 article published in the journal Geology linked the Prague earthquake with wastewater injection wells. According to state records, six homes were destroyed and 20 sustained major damage. A chimney collapsed through the roof of one house, injuring the woman inside. (She’s now suing two oil companies for her injuries. Both companies deny responsibility for triggering earthquakes.)

The Oklahoma Geological Survey said in a 2013 statement that the Prague earthquake sequence was most likely a natural occurrence. The agency’s interim director, Richard Andrews, and top seismologist, Austin Holland, could not be reached for comment despite repeated attempts.

Although most people are familiar with earthquake magnitudes, seismologists pay more attention to the intensity of ground shaking in assessing and predicting the damage an earthquake might cause. The Prague earthquake generated shaking up to intensity VIII, which the U.S. Geological Survey says includes “considerable damage in ordinary substantial buildings with partial collapse. Damage great in poorly built structures.”

That means that similar ground shaking near an urban area such as Oklahoma City or the state’s two major universities in Norman and Stillwater could cause extensive damage.

And seismologists say larger quakes in Oklahoma are certainly possible, though Ellsworth said there is more risk associated with frequent smaller earthquakes than rarer large ones.

“A 6 would surprise no one,” Ellsworth said. “You wouldn’t be shocked if a magnitude 7 were to occur.”

The U.S. Geological Survey’s current maps of seismic hazards intentionally ignore earthquakes believed to be influenced by human activities because the agency hasn’t known how to quantify the risk.

Now scientists and engineers are trying to find a way assess the potential hazard of these new earthquakes.

Building codes and insurance companies nationwide look to the geological survey to estimate the probability that a certain area will experience dangerous ground shaking as the result of earthquakes. Buildings can be designed to withstand even heavy shaking, but the costs to do so make it impractical in places that don’t have a history of earthquakes.

To determine which areas must meet that higher construction standard, a consortium of engineers, architects, construction manufacturers and other experts called the Building Seismic Safety Council uses the geological survey’s hazard models to develop recommended maps that eventually make their way into the building codes used by almost all local jurisdictions.

For decades, the risk for a given area was based on a 50-year period. But the latest wave of quakes challenges that thinking. As gas exploration and wastewater injection migrate into new areas, the earthquakes move as well. How should a building be insured that might be at risk for earthquakes for the next five years, but never after that? Or where there is currently no earthquake risk, but there might be in the future?

A U.S. Geological Survey team led by seismologist Mark Petersen is working on significant changes to the national hazard model to begin to address those questions. The team will propose several options for how to model earthquake risk in the next year, rather than over 50 years.

“It changes so rapidly that by the time it’s implemented, the seismicity patterns and rates have changed,” Petersen said.

But changes to local building codes won’t happen anytime soon. The seismic recommendations for building codes are updated every five years, and the Building Seismic Safety Council is poised to close the latest cycle at the end of February, using older geological survey data that doesn’t take into account the rash of new earthquakes. The soonest the new hazard models could be incorporated into the International Building Code is 2024, said Nico Luco, who represents the U.S. Geological Survey on the seismic council.

“It’s a very dynamic problem. It’s something that doesn’t fit well with the standard building code approach,” Luco said.

And changing the building code won’t address the biggest potential problem with induced earthquakes: the existing stock of buildings in areas that have never considered seismic risk.

“Your main issue is that you’re elevating the risk for everything that’s already there, and building codes don’t really do as much for that,” Luco said.

David Bonneville, a San Francisco architect and chair of a Building Seismic Safety Council committee on building code recommendations, said he doesn’t expect local governments to mandate changes on their own “unless something really bad happens.” If a larger quake “affected some small city in Oklahoma that has no seismic resistance at all, you can bet that will get people’s attention.”

Jim Greff, Prague’s city manager, said he and many other residents still haven’t gotten around to fixing all the cracks in their drywall, but the city isn’t yet considering action on its own to change its building codes.

“I still think it’s a low-risk hazard compared to a tornado coming through and doing a lot of damage compared to a big earthquake,” he said.

Greff said he’s not sure whether wastewater injection near the faults is responsible for the earthquakes. He’s looking to the state’s Corporation Commission and geological survey to make that determination.

“They’ve been injecting wastewater for way more many years than we’ve had earthquakes. Why is it all starting now, I don’t know,” he said.

In fact, injection at one of the wells near Prague had been going on for 17 years before the 2011 earthquake, the Geology article noted. Although most cases of induced seismicity begin soon after wastewater injection starts, the authors theorized that the cumulative injection over time finally crossed a critical pressure threshold that caused the nearby fault to slip.

The Oklahoma Corporation Commission regulates oil and gas production and wastewater disposal in the state and has shut down 19 disposal wells since 2013 due to concerns about earthquakes, said Matt Skinner, the commission’s spokesperson.

The commission has not officially acknowledged that disposal wells have caused specific earthquakes in Oklahoma.

Skinner said his agency is aware that induced seismicity in general is real and accepts that seismologists agree that wastewater disposal is the primary concern. So the agency is working with the Oklahoma Geological Survey to regulate well operators in new ways to address the increase in earthquakes.

New wastewater wells that are within a six mile radius of the epicenter of an earthquake magnitude 4.0 or higher must operate under a “yellow light” permit that allows the commission to immediately stop injection if more earthquakes occur. One such “yellow light” well near the Kansas border was shut down Tuesday after a magnitude 4.1 quake, the Tulsa World reported.

“This is a constantly evolving program,” Skinner said. “None of this is to be viewed in any way as, ‘Oh, look, we have an answer.’ It’s not.”