As Hurricane Katrina approached, many Americans for the first time learned about New Orleans’ precarious, below-sea-level orientation. The city is described as “bowl-like,” rimmed by levees and natural structures that might not hold back surging storm water — and might make drying out nearly impossible. It turned out that the analogy was imperfect. New Orleans is more like a TV dinner tray, and only the Ninth Ward ended up flooded.

After Katrina, anyway — a category 3 storm when it hit. But as sea levels continue to rise, and warming promises bigger storms, New Orleans’ complete submersion may be inevitable. From The Lens:

Stunning new data not yet publicly released shows Louisiana losing its battle with rising seas much more quickly than even the most pessimistic studies have predicted to date. …

Southeast Louisiana — with an average elevation just three feet above sea level — has long been considered one of the landscapes most threatened by global warming. That’s because the delta it’s built on — starved of river sediment and sliced by canals — is sinking at the same time that oceans are rising. The combination of those two forces is called relative sea-level rise, and its impact can be dramatic.

Scientists have come up with four scenarios of sea-level rise, ranging from .2 meters (8 inches) to 2 meters (about 6.5 feet). They’re using the mid-range figure, about 4.5 feet, to make local projections of relative sea-level rise.

For example, tide-gauge measurements at Grand Isle, about 50 miles south of New Orleans, have shown an average annual sea-level rise over the past few decades of 9.24 millimeters (about one-third of an inch) while those at Key West, which has very little subsidence, read only 2.24 millimeters.

For decades coastal planners used that Grand Isle gauge as the benchmark for the worst case of local sea-level rise because it was one of the highest in the world. But as surveying crews began using more advanced instruments, they made a troubling discovery.

Readings at a distance inland were even worse than at Grand Isle. “For example,” Osborne said, “we have rates of 11.2 millimeters along the south shore of Lake Pontchartrain — the metro New Orleans area. And inside the city we have places with almost [a half-inch] per year.

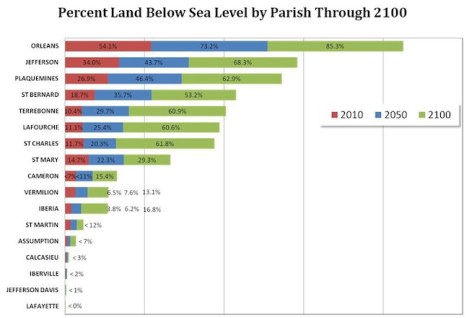

The Lens article includes this graph from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration:

The Lens/NOAAClick to embiggen.

Orleans parish, the one expected to be 85.3 percent under sea level by 2100, is home to the city of New Orleans.

Of course, as noted above, New Orleans is also more than half below sea level already. It’s like taking one of those cafeteria trays with the separate triangular sections and pushing it down into a bathtub. The more you push — or the more the water in the tub rises — the more it encroaches around the rim, surface tension holding it back. Eventually, as happened in 2005, it will give.

The only way to prevent that from happening is to build a larger lip around the outside, requiring a generous outlay of money and a great deal of urgency.

[NOAA’s Tim Osborne said,] “Based on the frequency of storms over the last century, we know we can expect 30 to 40 hurricanes or tropical storms to hit this area by the end of this century. Think of Isaac — not of Katrina — and add up the cost of that kind of destruction 30 or 40 times.

“During Isaac, Louisiana [Highway] 1 to Grand Isle was almost impassable. It will be impassable in a few decades unless something is done. Look at what happened to Plaquemines Parish from Category 1 Isaac. More and worse will happen in the next few decades.”

Osborne stressed the new figures mean the state’s Master Plan should be adjusted to meet the larger, faster-approaching threat.

“People are already questioning the wisdom of spending huge sums to protect Louisiana,” he said. “The state needs to make sure they’re proposing plans that will last more than a few decades, that they aren’t asking for billions to build things that might be ineffective before they are even finished being built.”

In 2009, Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal (R) openly opposed efforts to curb climate change. By 2100, of course, he’ll no longer be in office and his name will likely be forgotten. After all, can you name the governor of Atlantis?