My brother Michael and I stayed in the house for a day and a half after they declared the mandatory evacuation. We watched the fire on the mountains, watched it get closer. We both had come to expect this day. After all, this house had burned before.

Santa Barbara is an affluent town, and our house — a two-bedroom with a downstairs in-law apartment — is tucked into one of its nicest neighborhoods, in a canyon just outside the city limits.

But ours wasn’t the first house to stand in this spot. The original one, which belonged to my grandmother, burned to the foundation in the 1977 Sycamore Canyon blaze. Sparked by a guy and his girlfriend whose kite struck a power line, a raging late July firestorm whipped through the canyon, burning more than 200 homes. It took only about seven hours.

My father was living with my grandmother at the time. They got out safely but lost everything, except some family photos and the dog.

My grandmother rebuilt, and after she died in 2001 and left my father the house, he moved back in. But on Nov. 13, 2008, a fire in the same hills looked ready to take this house out, too.

Michael was 18 and home alone.

“I got home from school and I went into the house, and I remember two things being very out of place,” he tells me now, years later. “There was kind of this faint smell of burning wood. And then the other one was a lady running down the street screaming, ‘Fire!'”

Michael remembers thinking about that 1977 conflagration as he watched the the Tea Fire, as they called it, sizzle toward the house a little more than 31 years later.

The Santa Barbara Independent said the Tea Fire “spread quickly in an eerie similarity” to the ’77 blaze. My brother called my dad and they filled the car with art from the walls and a box of photos and then fled. When I talked to my dad on the phone that night, he seemed resigned to seeing a pile of char when they returned the next day.

The house didn’t burn. It was spared, while the fire burned over nearly 2,000 acres, destroying 210 nearby homes. When then-governor Arnold Schwarzenegger toured the destruction later, he said it looked “like hell.”

Now, six months after escaping the Tea Fire, Michael and I were watching the third fire to threaten our house in as many decades, tracking the flames on the hill, brushing the ash off the deck.

This one, the Jesusita Fire (“Jesus it’s a–nother fire?”) raged for nearly a week, took out 80 homes, injured 28 people, and charred most of the city’s botanical gardens. But as it lingered on the hillside, my brother, now jaded, played video games and read comic books. I packed the car and then watched from the deck, convinced that one of the flames might dart down into the canyon.

I called my dad, who was out of town, for advice. He said, “Do your best.”

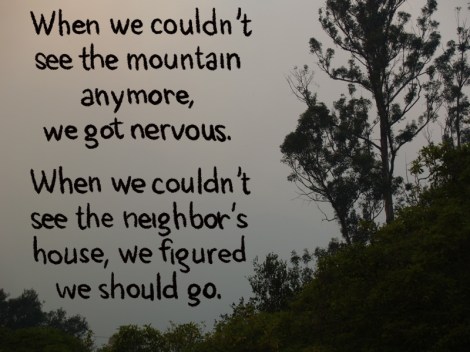

It was the smoke that finally drove us out. When we couldn’t see the mountain anymore, we got nervous. When we couldn’t see the neighbor’s house, we figured we should go.

This year, the first couple weeks of May were especially harrowing for Southern California fire country. A blaze in Ventura county, the next county south of Santa Barbara, reduced 44 square miles to ash, threatening thousands of homes and shutting down the highway — and my brother’s college, Cal State Channel Islands.

Smaller brush fires sparked up on hillsides and in neighborhoods throughout the state. I’m writing this while watching an 1,800 acre fire move through the Los Padres National Forest in Santa Barbara County on a cold, damp day. Thousands have been evacuated. Officials expect they’ll gain control of the blaze some time next week.

Over and over again, I hear people say “fire season came early this year.” But it doesn’t seem like there is a “fire season” anymore — it’s just a constant state of being.

U.S. wildfires are making a bigger impact than ever on our environment and on our lives. A lot of that is our own damn fault: We’ve built our houses in places prone to burning. The Santa Barbara foothills have traditionally burned around every 10 years — thousands, even tens of thousands of acres at a time.

This is how Southern California’s ecology works: Shrubby chaparral has evolved here over millions of years, periodically going up in flames. In turn, the chemical reactions from wildfires make the soil impervious to water, which leads to flooding, “raveling” erosion, and landslides.

It’s kind of a binge-purge thing.

“This is not random disorder, but a hugely complicated system of feedback loops that channels powerful pulses of climatic or tectonic energy (disasters) into environmental work,” Mike Davis writes of Southern California in his 1998 book, Ecology of Fear: Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disaster.

Besides having chosen poor locations to build their houses, the pioneering Californians who decided to live here more than 150 years ago made things even harder on generations to come. Deforestation and attempts to head it off in the mid-1800s actually set the state up for epic fiery disasters to come. New laws encouraged residents and developers to plant more trees, which they did — millions of non-native ones, like oily Blue Gum eucalyptus, the botanical equivalent of napalm.

In Berkeley now, there’s federal funding to support cutting down 22,000 non-native trees in order to reduce fire risk. Some local conservationists call it clear-cutting. But the people who live in the hills with those trees just don’t want to get burned again. The Oakland firestorm of 1991 that destroyed upwards of 3,500 homes and killed 25 people was blamed in no small part on those damn eucalyptus.

The eucalyptus is still here, but a lot has changed since the 1977 fire that took out my family’s house.

Climate change, for starters, is speeding up the natural binge-and-purge, fire-and-flood process. A new normal of higher temperatures and decreased rainfall has contributed to drought across much of the western and middle parts of the country. Rainfall and snowpack in California are at about half of normal levels, and almost the entire state is in moderate to severe drought right now.

My dad and other residents find some reassurance in a more active local fire department that promotes community-based preventative measures. “They have people walking neighborhoods, checking everything, and talking to every homeowner about what they should do,” he says.

The community and fire district aggressively trim the brush and plan evacuation routes. If you make a habit of not cleaning your gutters, letting them fill up with dry kindling, you’ll get a stern talking-to.

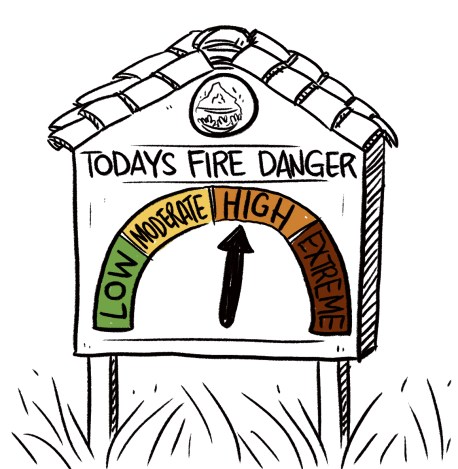

On the windy drive up to the house — through groves upon groves of that oily, flammable, alien eucalyptus — you pass the fire department, and a helpful sign warning of the day’s fire danger level. It hits “low” for a few weeks in January and February still, but Santa Barbara no longer has a fire season — there’s fire season, and “high fire season.” A phone app may next, like the one that just debuted in Alberta for their fire season.

This is life in fire country: Looking forward to an app that will warn you when your house might be burning down.

It’s a life that my dad could’ve escaped after the 1977 fire, but chose not to.

All these years later, he’s still bitter about the way the ’77 fire was treated in the media.

“Jimmy Carter didn’t declare it a disaster area I think because the news media took their spin on it to be rich people saving their horses,” he says. No federal disaster designation meant residents didn’t qualify for additional FEMA aid, and had to fend for themselves. My grandmother was a schoolteacher, my father a college student living at home — not exactly a picture of wealth.

Nonetheless, they rebuilt. “I think everybody wanted to rebuild because it was our homes,” he says. “And we thought that we could rebuild more fire-safe and we wouldn’t make the same mistakes as before.”

The main mistake my dad points to is having a wood-shingled roof.

“The wood roofs in the area contributed to the fire’s intensity and made it the disaster it was,” County Fire Marshall Don Oaks said at the time. Afterwards, the city altered the building code to require new structures be built with non-combustible materials, but many of the old houses still have their old roofs.

My dad is confident in his new one — “nice, big, cement” he tells me. The house is surrounded by concrete on all sides.

It is still made of wood, however, with a large deck that extends out in front. As the 2008 Tea Fire approached the house, my brother tried to work with it.

The 2009 Jesusita Fire that Michael and I watched from the deck drove a third of Santa Barbara’s residents from their homes. Happily, our house survived again, though many of our neighbors were not so lucky.

The intensity of the Tea and Jesusita was the first major indication of a new hotter paradigm here. Scientists now predict that the biggest climate change for California will be an “alarming, increasing trend” in these major fires over the next decades burning more intensely and spreading faster and wider, especially where there’s a lot of fuel to burn.

Gov. Jerry Brown — who reassured my young, angry, houseless dad at a Santa Barbara town hall meeting in 1977 — says we’ll have to roll with it.

With fire risk on the rise everywhere, some places are instituting new approaches to fire prevention. On the cuter side of things, goats and sheep are grazing the hills, chewing up flammable grasses. The less cute: pouring herbicide all over those non-native plants.

But once a fire is burning, options are limited. Residents here pay a fee to the fire district for additional protections, but sequestration in Congress has cut into federal funding for wildfire suppression nationwide. More aggressive and affluent homeowners go further, installing expensive systems like FoamSafe, that coat your house in non-flammable goo. Most just cut their trees and hope for the best.

The eucalyptus in Santa Barbara smells like fresh danger. What is it about people who know that danger so well, and still choose to stay? I figure it’s one part rationalization, one part Southern California disaster fatigue, two parts stubbornness.

“We do the fire safety and we clear the brush and we built the house with a cement roof and the house is surrounded by cement and we have fire insurance and we pay our extra fire district fee, and … we worry about it,” says my dad. “But it’s my home. If I lived somewhere else I’d have a tornado or a hurricane.”

And ironically, with each fire the new house survives, it builds its immunity to the fire next time. I saw it when we returned to the house a week after the Jesusita Fire and found everything fine, if covered in ash: With all the crispy chaparral burnt up, there’s no fuel to carry a blaze to our doorstep — for a while, at least.

It still feels like it’s only a matter of time until the house catches fire and burns to the ground, until my family loses all of it. Again. It’s always felt that way.

But when I press my dad on the subject, his response is, essentially: Would that really be so bad?

“To have an event where it just clears out all your stuff and you’ve got nothing left, that’s somehow psychologically liberating,” he says. “I didn’t fall in love with things like I think I would have if I didn’t have the experience of being cleaned out like that. We got the family photos and the dog out. We were fine … And now I’ve got a better life philosophy.”

In the end, I think people like my dad stay because they love it there. And who can blame them? The coastal weather is balmy, the bike lanes plentiful, and the burritos delicious — even in an inferno.

For decades people have been trying to engineer California to be less disastrous. They have not done a good job. But I don’t think those who choose to live here are really drawn to disaster like so many flitting moths.

Faced with the hot history of the place and its even hotter future, they still have a kind of pioneer pride. They’re stickers. Hell, this is their home, and they’re not giving it up for anything.

I almost admire it. But I also don’t live in Santa Barbara anymore.

I’ve opted for earthquake country instead.