So, how’s humanity doing?

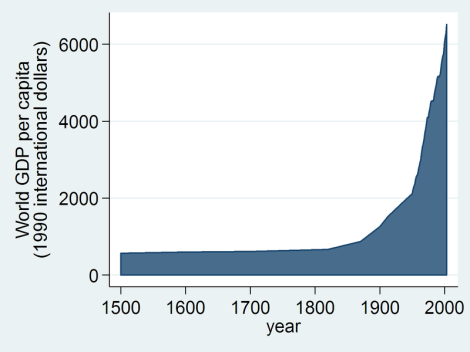

Good question. One way of answering is to look at global per-capita GDP — that is, the average amount of economic activity per person in the world. From that perspective, humanity is kicking ass:

WikipediaClick to embiggen.

We’re getting richer!

Here’s the thing, though: While GDP has come to serve as a stand-in for human welfare, it was not originally developed for that purpose. What’s more, it kind of sucks for that purpose. Objections to GDP as a measure of human welfare are as old as GDP itself; I’ve written about them before. It doesn’t distinguish between welfare-enhancing economic activity and the welfare-degrading kind. It doesn’t value natural capital. It doesn’t incorporate life satisfaction or economic inequality. And so on. Any true measure of human welfare should be far more nuanced.

So what to use instead? One alternative measure is the Genuine Progress Indicator, or GPI, an attempt to combine personal consumption expenditures (what GDP captures) with a few dozen other positive and negative indicators, including crime, pollution, inequality, the loss of ecosystem services, the value of domestic labor, self-reported happiness, and so forth.

(There is a long, involved, and contentious literature on GPI and other alternative metrics. Needless to say, no aggregate measure of welfare is precise; all reflect their own contestable assumptions; all have their shortcomings. But it seems to me that almost any of them, including GPI, are preferable to simple GDP, which after all includes contestable assumptions of its own.)

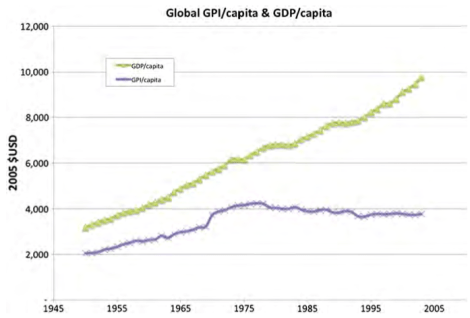

In a new paper in the journal Ecological Economics, a team of researchers attempts something novel: to aggregate all the available GPI data in various countries into a global per-capita GPI.

Their top-line finding is pretty astonishing: Global per-capita GPI peaked in 1978 and has declined since. Put another way: Some time around 1978, the rise in aggregate global economic activity ceased enhancing global economic welfare — GDP and GPI parted ways.

Ecological EconomicsClick to embiggen.

Why do they split? The critical difference between the two is that GPI incorporates the spending down of natural capital as an economic cost — it’s no coincidence, the authors note, that 1978 is also about when “global Ecological Footprint exceeded global Biocapacity” for the first time.

What’s more, the researchers found that GDP/capita and GPI/capita rose together until the former hit about $7,000; at that point, GPI stops rising alongside it:

Ecological EconomicsClick to embiggen.

It’s important to be careful with conclusions here. It’s not necessarily that making more money than $7,000 makes people less happy. I know I’d be happier with $700,000 than $7,000. Rather, at that level of global economic growth, the cumulative cost of negative indicators like lost natural capital, inequality, and pollution start to cancel out the welfare gains of growth.

Just as a thought experiment, let’s say we capped global per-capita GDP at $7,000 (none of us reading this would like that much, I suspect) and total global GDP at its current level, $67 trillion. How many people could the earth support at that level? “No more than 9.6 billion” (for reference, we are at 7.1 billion, headed to 9.6 billion by 2050, so it’ll be a tight fit). The authors note, rather wryly I thought, that to reach this exalted state, “variations in income would need to exist between and within nations, however these disparities should be much smaller than they are today.” Yes. Much.

This is the radically egalitarian message of this kind of research: maximizing global economic welfare from this point forward will involve more redistribution than growth. The simple, headlong, unequal growth on the 20th century is no longer working.

Of course each country has it’s own GDP/GPI story to tell. There’s lots of good stuff in the paper about individual countries, and also how GPI stacks up against other indicators like ecological footprint, the Human Development Index, life satisfaction, the Gini coefficient, and so on. Dig in if you like that kind of stuff.

——

By way of discussion, it’s worth noting that this paper’s results tack somewhat against a good bit of current research showing that the correlation between rising income and rising happiness holds pretty much forever, though it loses strength higher up. This is the new hip stance in these matters: “Yes, money really can buy happiness.” (Or put another way: that there may be no Easterlin Paradox.)

What explains the disparity? Can we increase our welfare by growing more, or can’t we? Again, I think the key difference is that GPI is scoring the loss of natural capital as a cost. As the authors put it:

Economic activity, it should be recognized, is undertaken to generate a level of economic welfare greater than what can be provided by natural capital alone. For the GPI to properly reflect this reality, it is necessary to subtract the permanent loss of natural capital services.

This explains the apparent contradiction. As finite resources are consumed, the welfare (and happiness) of current people rises, while the natural capital necessary to sustain economic activity declines. GDP will only pick up on the former; GPI incorporates the latter.

It ends up, as so many things do, coming down to how much value one places on the welfare of future generations. Is the “humanity” whose welfare we are attempting to maximize currently alive humans, or the species in its whole great arc on this planet?

To some folks, the unsustainability of running faster and faster through finite resources seems self-evident. Others, however, hate this sort of thinking. They believe that market forces will push human beings to discover new or more sustainable natural resources, or squeeze more out of current ones (as we are doing now with oil). They believe that economic growth, not necessarily defined as material throughput but simply as increases in welfare brought about by mutual trade, has no limit because human ingenuity has no limit. There is no petri dish for humanity — or rather, there’s no reason our petri dish can’t go on expanding, forever. Man Will Overcome.

The way I think about the question is: Are we a biological species or an economic species? Set aside an hour or two some day and read Charles C. Mann’s magnificent “State of the Species.” It frames the question in the clearest possible terms.

It would be no surprise at all for a biological species to expand its population into overshoot, destroy its habitat, and go extinct. It’s what you would expect of an organism with few competitors. Mann discusses the work of scientist Georgii Gause, working in the 1920s. Gause’s original experiment was simple but brilliant: five test tubes, each with a few drops of broth, each containing five single-celled protozoans of a single species. After a week’s observations, here’s what he found:

What Gause saw in his test tubes is often depicted in a graph, time on the horizontal axis, the number of protozoa on the vertical. The line on the graph is a distorted bell curve, with its left side twisted and stretched into a kind of flattened S. At first the number of protozoans grows slowly, and the graph line slowly ascends to the right. But then the line hits an inflection point, and suddenly rockets upward—a frenzy of exponential growth. [See: global GDP graph at the top of this post.] The mad rise continues until the organism begins to run out of food, at which point there is a second inflection point, and the growth curve levels off again as bacteria begin to die. Eventually the line descends, and the population falls toward zero.

In nature, as Darwin so perspicaciously noted, natural selection keeps this process in check. Organisms have competitors and limited ecosystems. But in a petri dish or test tube, free of competitors, a species will race to the limit and shoot past it. It is the nature of life, to propagate itself. Mann writes:

By luck or superior adaptation, a few species manage to escape their limits, at least for a while. Nature’s success stories, they are like Gause’s protozoans; the world is their petri dish. Their populations grow exponentially; they take over large areas, overwhelming their environment as if no force opposed them. Then they annihilate themselves, drowning in their own wastes or starving from lack of food.

In short, a biological species as dominant as ours, largely free of competitors and still with large stocks of natural capital to burn through, should be expected to hit limits and suffer catastrophes. And it won’t be pretty:

If we follow Gause’s pattern, growth will continue at a delirious speed until we hit the second inflection point. At that time we will have exhausted the resources of the global petri dish, or effectively made the atmosphere toxic with our carbon-dioxide waste, or both. After that, human life will be, briefly, a Hobbesian nightmare, the living overwhelmed by the dead. When the king falls, so do his minions; it is possible that our fall might also take down most mammals and many plants. Possibly sooner, quite likely later, in this scenario, the earth will again be a choir of bacteria, fungi, and insects, as it has been through most of its history.

Whee!

However. If we are an economic species — a welfare-maximizing species, a rational species — we will look ahead, anticipate problems, and innovate solutions. We will decouple economic growth from material throughput and grow without limit, eventually into space, bounded only by our own imaginations. “To seek out new life and new civilizations / To boldly go where no man has gone before.”

So which is it, collapse or transcendence? Kunstler or Kurzweil?

I’ll admit to being somewhat schizophrenic on this question. I’m very much attracted to the notion of boundless ingenuity. But the raw truth is that we are not, in fact, looking ahead, anticipating problems, and innovating solutions — not on a broad scale. We are not taking the kind of drastic action necessary to shift to long-term sustainability. In fact, it’s proving difficult for us even to talk about it sensibly or govern in the right direction. Mann again:

Not only is the task daunting, it’s strange. In the name of nature, we are asking human beings to do something deeply unnatural, something no other species has ever done or could ever do: constrain its own growth (at least in some ways). Zebra mussels in the Great Lakes, brown tree snakes in Guam, water hyacinth in African rivers, gypsy moths in the northeastern U.S., rabbits in Australia, Burmese pythons in Florida—all these successful species have overrun their environments, heedlessly wiping out other creatures. Like Gause’s protozoans, they are racing to find the edges of their petri dish. Not one has voluntarily turned back. Now we are asking Homo sapiens to fence itself in.

What a peculiar thing to ask! Economists like to talk about the “discount rate,” which is their term for preferring a bird in hand today over two in the bush tomorrow. The term sums up part of our human nature as well. Evolving in small, constantly moving bands, we are as hard-wired to focus on the immediate and local over the long-term and faraway as we are to prefer parklike savannas to deep dark forests. Thus, we care more about the broken stoplight up the street today than conditions next year in Croatia, Cambodia, or the Congo. Rightly so, evolutionists point out: Americans are far more likely to be killed at that stoplight today than in the Congo next year. Yet here we are asking governments to focus on potential planetary boundaries that may not be reached for decades. Given the discount rate, nothing could be more understandable than the U.S. Congress’s failure to grapple with, say, climate change. From this perspective, is there any reason to imagine that Homo sapiens, unlike mussels, snakes, and moths, can exempt itself from the natural fate of all successful species?

In his conclusion, Mann compares what’s necessary to a species-wide form of what the Japanese call hara hachi bu: “belly 80 percent full.” The brain receives the body’s signal of satiety long after it is sent; during its transmission, we eat to excess. So the way to stay healthy, to eat the appropriate amount, is to stop eating before feeling entirely full. One way of looking at these new results on GPI is that they are an early indicator: we are hara hachi bu. We have enough, if we would share it more equitably. But GDP shows that we’re still eating furiously.

Can a successful species stop before it is stuffed and sick? It’s never been done before, but humans have done lots of things that have never been done before. Maybe human intellect and imagination are something truly new in the world. After all, concludes Mann …

… it is terrible to suppose that we could get so many other things right and get this one wrong. To have the imagination to see our potential end, but not have the imagination to avoid it. To send humankind to the moon but fail to pay attention to the earth. To have the potential but to be unable to use it—to be, in the end, no different from the protozoa in the petri dish.