So, you’ve been watching the protests and unrest unfold around the grand juries’ non-indictments of the police who killed Michael Brown and Eric Garner. You’re appalled that the criminal justice system would allow those who are supposed to serve and protect us to take someone’s life and not be held criminally accountable. You’ve witnessed the battle slogans “Black Lives Matter” and “I Can’t Breathe” proliferate from a few protest signs in the street to NBA players wearing them during televised games, to the police themselves carrying the sign in solidarity.

You’re sympathetic to the cause, ready to lay down in the streets for it if need be. But you’re not sure if that’s the appropriate response, or what an adequate response looks like. After all, you’re an environmentalist — a tree-hugger, not necessarily a race-hugger, or at least you’re not used to embracing protests around racism. Or maybe you lead an organization or a company that doesn’t count racial justice as part of its core mission. You’re worried about alienating certain constituents, colleagues, family members, or of being accused of straying from your organization’s central cause.

Bottom line: You believe in the Black Lives Matter movement, and you want to show your support, but you don’t know how to do it without offending others who matter to you as well. What should you do?

My answer: I don’t know. But I have spoken with quite a few people who are either grappling with this question, or have found ways to answer it. Here’s some of what I learned that hopefully can be of use.

First, know that you’re not alone. You’re not the only person with anxiety about how to support the Black Lives Matter movement, and that goes for whether you’re white, black, Latino, Asian, Catholic, agnostic, environmentalist, or fossil fuel lover. Consider that the national Alpha Kappa Alpha and Delta Sigma Theta sororities recently put out guidelines for their members on how not to engage with the Black Lives Matter protests … and these are black sororities. But there are organizations and companies that have found ways to show support even if it looks like an unnatural alliance.

The question of how to engage came up at Triple Pundit, a news site that covers businesses invested in environmental responsibility. Editor-in-chief Jen Boynton spoke with Cecily Joseph, vice president of corporate responsibility for the anti-virus computer company Symantec, who said that addressing issues like Ferguson is “where brave companies demonstrate leadership.” Boynton struggled with whether it was appropriate to write the piece at all, though. Triple Pundit rarely covers protests, and when they have it has been when business interests were at stake, as with Occupy.

Boynton told me she personally supports Black Lives Matter, even as it’s entangled her in some messy arguments about it on social media. “To me, Black Lives Matter isn’t anti-police. It’s anti-police brutality, which I think we can all be in favor of,” she said. “My awkwardness is more about how to talk about it. But I decided to say something anyway because the alternative of staying silent is worse.”

It’s not just the corporate world. Plenty of people involved in social and environmental activism are struggling with how to engage. The Sierra Club caught so much shit from members for supporting the protests that the group’s president, Michael Brune, had to write a public letter explaining its position.

It can be trickier for green advocates on the ground, as Caitlin Johnson, lead organizer for the Ohio-based Communities United for Responsible Energy, told me. Johnson works mainly with people in Appalachia, helping them resist fracking operations that have been encroaching on their homes. The demographics of these areas — low-income, mostly white Republicans — aren’t exactly the kind that dance neatly with racial justice campaigns.

And yet, Johnson lives in Cleveland, where the U.S. Justice Department just handed a smackdown to the police department for its patterned history of discrimination and violence. Her mother’s family lived in the neighborhood where 12-year-old African-American Tamir Rice was recently murdered by Cleveland police. In August, John Crawford III, 22, was shot dead by police in a Walmart in Beavercreek, Ohio, though posing no threat. As with the police who killed Michael Brown and Eric Garner, Crawford’s killer was not indicted.

How does one focus on fracking in Appalachia when police are fracturing communities by killing black men and boys?

“I’ve been thinking a lot about Black Lives Matter and how we’re fighting the same battle,” said Johnson, who is white. “At the end of the day, the same corporate interests that are behind these private prisons and mass incarceration are also behind poisoning our air and water.”

Johnson said her goal “is to one day show poor and working-class white folks in Appalachia how they are victimized by the same institutions that victimize black folks who live in urban areas.”

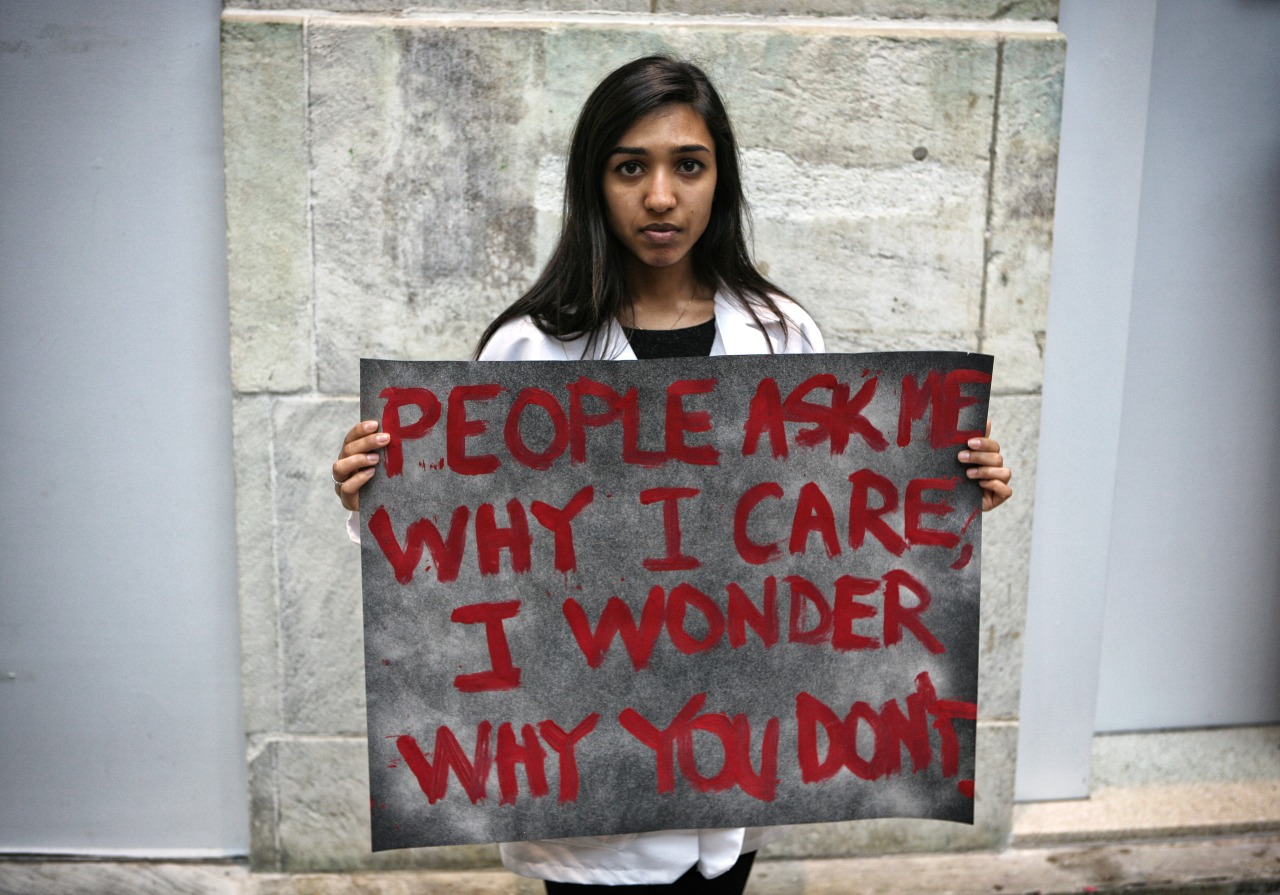

Other groups are finding ways to speak boldly on this issue, even if their mission appears to have little to do with anti-black racism. Wednesday, future physicians and surgeons from over 70 medical schools, including Harvard, Duke, and Yale, staged a die-in to support the Black Lives Matter movement. One of the students involved who I spoke with, Tamara Rodriguez Reichberg of Harvard, said her support also extended to the environmental justices that played a role in Eric Garner’s death.

“Racial and environmental injustice are linked to the same systemic problems of our society,” said Reichberg. “Both manifest in disease, and both are concerns to public health. Racial injustice as we know it is expressed through institutional racism and structural violence that affect the health of Black and Latino patients. Environmental injustice, too, disproportionately impacts Black and Latino patients. The role of medicine is to alleviate human suffering. As practitioners of medicine, we must treat not only the symptoms of suffering, but also its causes.”

Similarly, students from Harvard’s Graduate School of Design have gotten involved, launching a hackathon last month in response to Brown’s killing in Ferguson, Mo. The architecture students’ goal is to create “a national map that visualizes how these killings are related to institutionalized racism in the 21st century … and show how nuanced racism … exists in the fields of housing, food, transportation, education, prison justice, employment/economic justice.”

One thing worth noting in these student-led initiatives is the sheer diversity of those involved. I can imagine it might be tough finding an entrance ramp into the Black Lives Matter foray if your organization has a predominantly white staff or all-white leadership. That kind of homogeneity can make it difficult to discuss these matters even internally without a panoply of racial backgrounds and experiences at the table.

This is why diversity matters, especially in the environmental world, said Patrice Simms, who teaches environmental policy at Howard University Law School in D.C. Before that, he served as an attorney for both the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Department of Justice, as well as senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council. He’s also a member of Green 2.0 working group, which has been advancing action on helping environmental groups diversify their staffs and leadership.

“If the organizations were more diverse and working on issues in a broader way, then they would immediately see how the issues raised by the Black Lives Matter movement intersects with concerns that the environmental movement faces,” said Simms. “In a world where environmental organizations, corporations, and other institutions were truly diverse, it would be unthinkable for them to remain silent about these fundamental issues of bias and fairness and justice. Absent that kind of diversity, they have the luxury to ignore these kinds of issues.”

The original mission of the environmental movement, in fact, was deeply rooted in broader social justice and civil rights movements, said Simms — something I’ve written a bunch about here at Grist. Somewhere along the line, these issues all got separated, to the point that many well-meaning environmentalists want to support the Black Lives Matter movement, but fear reprisal from colleagues or accusations of mission drift. I have no concrete solution for those who are grappling with this, but a starting point might be to remind their colleagues what the environmental movement was truly about to begin with: justice.