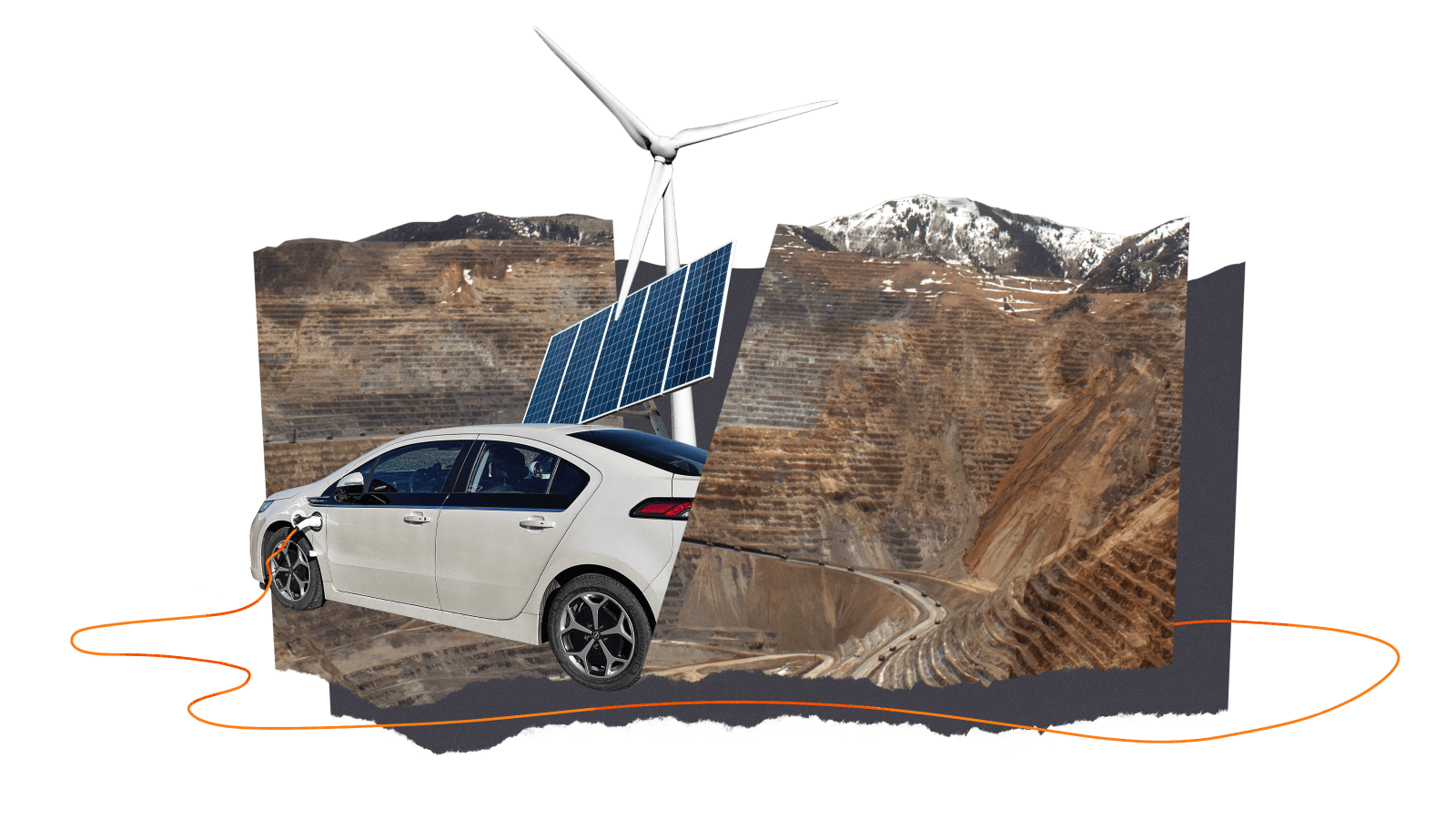

To get the United States running on clean energy will require a lot of metal: A single electric vehicle battery pack could contain around 8 kilograms of lithium, 14 kilograms of cobalt, and 35 kilograms of nickel. A wind turbine can contain more than 4 tons of copper.

Over the next several decades, global demand for these “critical minerals,” a group that includes lithium, cobalt, nickel, and copper, is projected to increase by 400-600 percent driven by a surge in manufacturing of renewable technologies. For some metals like lithium and graphite, it could skyrocket by as much as 4,000 percent.

China dominates this global market, processing 50-70 percent of the world’s lithium and cobalt. But the Biden administration has taken a hard line against providing tax breaks to manufacturers who source metals from countries without free trade agreements with the U.S. That means that developers of technologies like electric vehicles and wind turbines need to find new supply streams – and fast.

But the process of extracting metal and mineral deposits from the earth, known as hardrock mining, has a reputation for contaminating local watersheds and causing irreparable environmental damage. That’s why domestic mining projects often encounter legal challenges and protests when they are initially proposed.

“It’s very hard to open up a mine in the United States. No one wants a mine in their backyard,” said Jordy Lee, a program manager at the Payne Institute for Public Policy at the Colorado School of Mines. “It’s not clear how the U.S. is supposed to mine and produce all these minerals when there’s so much pushback against the industry.”

Domestic mining is governed by a 150-year old law that critics characterize as a relic of the Wild West Era. Unlike laws regulating other extractive industries like oil and gas, the General Mining Law of 1872 doesn’t require companies to pay federal royalties on the resources they extract from public lands. A patchwork of more recent legislation regulates the environmental impacts of mining, but since it is distributed across multiple federal agencies, it can take years before a project gets approved. The Biden administration has recently passed a batch of bills to incentivize the buildout of a domestic supply chain to mine and process the minerals necessary for weaning the country off fossil fuels.

Now, Senator Joe Manchin, Democrat of West Virginia, is proposing legislation that would speed up permitting for major energy and infrastructure projects, including mining. The National Mining Association has said that the bill would help hardrock mining companies meet rising demand by providing some certainty that their projects will get greenlighted.

Environmental advocates and community groups whose land risks destruction from proposed projects see it differently. Mining activity has left deep scars across the American West, where the Environmental Protection Agency estimates that 40 percent of watersheds have been contaminated by hardrock mines. This environmental degradation has had particularly severe consequences for indigenous communities because many live close to the country’s largest deposits of nickel, lithium, cobalt, and copper.

The history of mining in the United States is inextricably linked to the history of westward expansion. The General Mining Law of 1872, inked 150 years ago by President Ulysses S. Grant, proclaimed mineral extraction to be the highest and best use of U.S. public lands, and encouraged waves of settlers to move West, displacing indigenous people from their native lands.

A century later, the Cold War spawned another mining boom, as uranium was needed for nuclear weapons. Government incentives helped develop mining from an industry of pickaxes and shovels to one that employed massive machinery to blast through mountaintops and scrape the surface of the earth. At the time, the only law governing mining was the one Grant had signed in 1872, and companies were allowed to abandon sites without cleaning up the toxic by-products they left behind. The consequences of this unregulated activity were disastrous: More than 22,000 abandoned hardrock mines around the country still pose an environmental hazard to the surrounding area.

After a national environmental movement swept through the nation in the 1960s, President Richard Nixon signed a series of laws that changed how the mining industry is regulated, including the Clean Water Act, the National Environmental Policy Act, and the Endangered Species Act. Regulations passed in the 1970s mandated that companies clean up project sites after they finished. But by the time these measures were implemented, demand for critical minerals had waned as the Cold War came to a close. When the tech boom started in the late 1990s, companies needing lithium and other metals for cell phone batteries and high-speed cables sourced them from other parts of the world. As countries like China and Chile built out their hardrock mining industries, the U.S. focused on developing other industries, like oil and gas.

“We used to be the largest lithium producer in the world and now we’re one percent of it,” said Ben Steinberg, a former Department of Energy official who represents the mining industry at the public relations firm Venn Strategies in Washington, D.C.. “So the knowledge about how mining operates, and what its value is to the country, is largely lost.” This is all the more challenging, Steinberg said, because many of the people who live near new extraction projects are against mining at the very moment when the country suddenly needs a lot more of it.

“It’s a big threat,” said Joe Kennedy, a Western Shoshone activist who spoke to Grist after a day of lobbying against the mining industry in Washington, D.C. Western Shoshone lands, which stretch across parts of Nevada, California, Idaho, and Utah, have been contaminated by uranium extraction and open pit gold mining. Today, numerous companies are looking to open new gold and lithium mines in the region. “We’re playing with fire, and we’re probably going to get burned.”

The question of how much the U.S. should develop its hardrock mining sector is hotly contested. The impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on the European economy has highlighted the risk of relying too heavily on foreign nations for critical resources. Numerous environmental organizations have pointed out that the development of a circular economy in which critical minerals are recycled rather than continually extracted could decrease the country’s need for mining. The environmental watchdog Earthworks estimates that recycling has the potential to reduce demand by approximately 25 percent for lithium, 35 percent for cobalt and nickel, and 55 percent for copper by 2040. But more recycling isn’t likely to meet the demands for critical minerals anytime soon.

“This isn’t the choice of yes or no for the need for minerals that come from the ground,” said Steinberg. “This should be a conversation about how.”

Both Lee and Steinberg think it’s possible to mine for critical metals sustainably with the consent of locals, and also avoid repeating the mistakes of the twentieth century. But doing so will require Congress to pass stronger laws and standards.

That’s why the Biden administration recently convened an interagency working group on mining reform, which has been directed to come up with recommendations for creating new environmental standards and defining procedures for incorporating local recommendations.

But some people living near proposed project sites have argued that certain parts of the country are simply too culturally precious to mine. Take Chi’chil Biłdagoteel (known in English as Oak Flat), a forested region of southeast Arizona where mining giants Rio Tinto and BHP want to build a copper mine on land sacred to members of Western Apache and Yavapai tribes. The companies hope to extract the metal material by blasting through underground ore deposits, a method that could create a crater up to two miles wide and 1,000 feet deep. Tribal members and their allies have been fighting the project for nearly two years in federal court.

“There are different types of sustainable mining, and one of those is the actual process of choosing where,” said Blaine Miller-McFeeley, a senior legislative representative at Earthjustice. “That is just as important as choosing how.” He called the bill Manchin is pushing in Congress “a sellout to industry” because it would enable mining companies to force through a project without taking concerns of the community into account, undermining the administration’s purported goal of giving locals a say in the permitting process.

Kennedy said that after witnessing decades of biodiversity loss and water contamination on Western Shoshone land at the hands of mining companies, he is skeptical that domestic hardrock mining will become a truly sustainable industry.

“There would have to be a lot of built trust,” Kennedy said. “I mean, the Western Shoshone should be the ones to say yes or no to this type of project because it is Western Shoshone territory. It is Shoshone land, and that really is the bottom line.”

To Steinberg, Manchin’s bill is a “step in the right direction,” because it would streamline an outdated permitting process, but he agreed that there are certain places that should be off limits.

“We have the Grand Canyon. Probably shouldn’t mine in the Grand Canyon,” Steinberg said. “But we can’t plan millions of years of geology, and earth’s deposits are where they are, so we need a process and place for the industry and governments and the public to come together to make this vision about where to mine.”