This story was originally published by Mother Jones and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Jennifer Gill got pregnant with her first child when she was in eighth grade. She didn’t finish high school, but she got her GED during a stint in prison for forgery. For most of her working life she was a waitress in and around the town of Oildale, a suburb of Bakersfield in the southern tip of California’s Central Valley. “We come from backgrounds where minimum wage is the best we can hope for,” she says. Then, four years ago, Gill happened to see a television commercial for a solar-panel installation course at a local community college.

Within a few weeks, the 46-year-old was out in the field, helping install photovoltaic panels for the engineering behemoth Bechtel and making more than $14 an hour. She quickly got another job installing panels for another solar farm, this time for over $15 an hour. Now she’s in an apprenticeship program with the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, and for the first time in her life she has retirement benefits. At her urging, her younger sister, who had lost her job at a local Dollar Tree, signed up to become a solar-panel installer. Other friends followed suit. “Some of these folks have bought houses now,” Gill says.

Ivanpah Solar under construction, near the Mojave Desert and the border of Nevada.Jamey Stillings

This past fall, Gill was working at Springbok 1, a solar field on about 700 acres of abandoned Kern County farmland. In a neighboring field, workers recently broke ground on Springbok 2. A few months earlier, 35 miles south on the flat, high-desert scrubland of the Antelope Valley, workers locked into place the last of 1.7 million panels for the Solar Star Projects, owned by Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway. The panels are arrayed in neat rows across 3,200 acres, an area nearly four times the size of New York’s Central Park. In June, Solar Star began sending 579 megawatts of electricity — making it the most powerful solar farm in the world — across Southern California, where it powers the equivalent of more than a quarter of a million homes.

For over a century, Kern County made much of its money from gushing oil fields. The town of Taft still crowns an oil queen for its anniversary parade. But with the oil economy down, unemployment stands at 9.2 percent — far above the national average. Local politics remain deeply conservative. Merle Haggard, who was from Oildale, wrote his all-time biggest hit, “Okie From Muskogee,” about the place (“We don’t burn no draft cards down on Main Street”). Today, the region is represented in Congress by Republican Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy, a cheerleader for the oil industry.

Nature, however, sculpted this landscape for solar and wind. The sun bears down almost every day, and as the valley floor heats up, it pulls air across the Tehachapi Mountains, driving the blades on towering wind turbines. For nearly eight years, money for renewable energy has been pouring in. About seven miles north of Solar Star, where sand-colored hills rise out of the desert, Spanish energy giant Iberdrola has built 126 wind turbines. French power company EDF has 330 turbines nestled in the same hills. Farther north, the Alta Wind Energy Center has an estimated 600 turbines. Together, these and other companies have spent more than $28 billion on land, equipment, and the thousands of workers needed to construct renewable-energy plants in Kern County. This new economy has created more than 1,300 permanent jobs in the region. It has also created a bonanza of more than $50 million in additional property taxes a year — about 11 percent of Kern County’s total tax haul. Lorelei Oviatt, the director of planning and community development, says, “This is money we never expected.”

But the sun and wind were not the most important forces in the transformation of the region’s economy. The biggest factor was the state government in Sacramento, where for many decades power players — Republicans and Democrats — have been marching toward a carbon-neutral existence.

Today, California can claim first place in just about every renewable-energy category: It is home to the nation’s largest wind farm and the world’s largest solar thermal plant. It has the largest operating photovoltaic solar installation on Earth and more rooftop solar than any other state. (It helps to have a lot of roofs.) This new industry has been an economic boon as well. Solar companies now employ an estimated 64,000 people in the state, surpassing the number of people working for all the major utilities. California has attracted more venture capital investment for clean-energy technologies than the European Union and China combined. Even the state’s manufacturing base is experiencing a boost; one of California’s largest factories is Tesla Motors’ sprawling electric-vehicle assembly plant in the Bay Area.

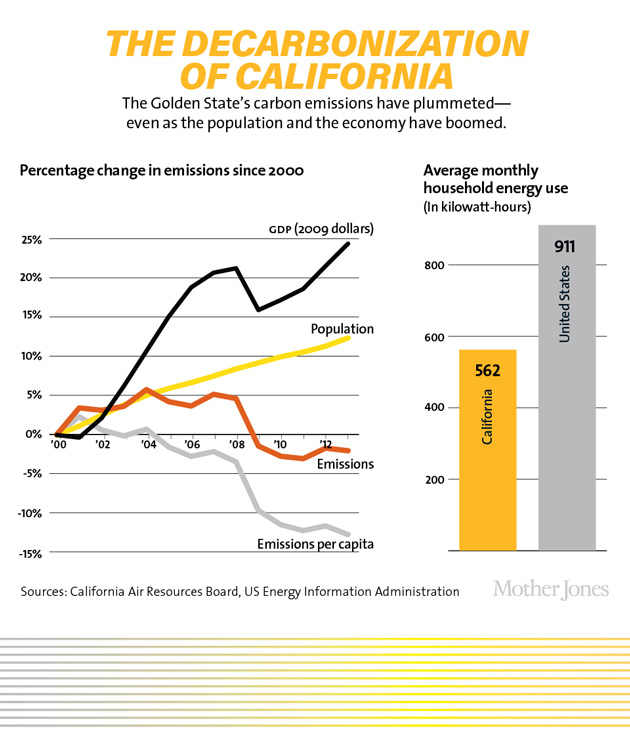

All of these advances have undercut a fundamental tenet of economics: that more growth equals more emissions. Between 2003 and 2013 (the most recent data), the Golden State decreased its greenhouse gas emissions by 5.5 percent while increasing its gross domestic product by 17 percent — and it did so under the thumb of the nation’s most stringent energy regulations.

That achievement has made California the envy of other governments. At the climate change summit in Paris last December, Gov. Jerry Brown floated about like an A-list celebrity. Reporters trailed after him, foreign delegations sought his advice, audiences applauded wherever he spoke. And Brown, reveling in the attention, readily offered up California as a blueprint for the world.

When his term ends in two years, Brown will have been in elective office in California for 34 years, including 16 as governor, a job he first took on in 1975 and reclaimed in 2011. At 77, Brown, whose long résumé includes a stint at seminary, is the rare American politician who muses openly about whether humanity has already “gone over the edge,” calls climate change deniers “troglodytes,” and blames global warming for every natural calamity that befalls California, from drought to wildfires, even when he’s criticized for taking the connection too far.

In what is likely to be the last chapter of his elective career, Brown is now embarking on a bold social experiment that will define his legacy. This past October, he reset California’s goalposts by adopting some of the most ambitious carbon-reducing rules in the world. SB 350, the Clean Energy and Pollution Reduction Act, says that by 2030, California must get half its electricity from renewables and it must double the energy efficiency of its buildings. These measures are intended to push the state to its ultimate goal: by 2050, cutting greenhouse gas emissions to 80 percent below the level it produced in 1990 (the baseline much of the world — but not the United States — agreed to pursue in the 1997 Kyoto climate treaty). It is this last measure that makes California’s global warming mission far more sweeping than any nation’s, because while countries with ambitious targets like Germany and Japan have shrinking populations, California will be home to 50 million people in 2050, two-thirds more than in 1990.

During his inaugural address last year, Brown detoured from the usual platitudes to launch into a lecture on his environmental policies, from new vehicle and fuel standards to plans for better managing rangelands and forests. “California, as it does in many areas, must show the way,” he told his audience. “We must demonstrate that reducing carbon is compatible with an abundant economy and human well-being. So far, we have been able to do that.”

But the state’s current achievements look easy compared with the new mandates. That’s because a lot of low-hanging fruit has already been picked: The best wind power sites are already chock-full of turbines, and complex land use rules make it difficult to find more locations for massive solar installations. What’s more, scientists and businesspeople will have to come up with new technologies, such as batteries that can hold enough power for a house at a price most homeowners can afford. And there is no clear understanding of how much it will cost: Californians may pay higher electricity and fuel prices; carbon-emitting industries may have to pay more for production. Even then, the gains are fragile and can be undermined by changes in consumption patterns, the economy or, as took place this past winter in Los Angeles, industrial accidents. There, a methane leak from a gas facility which went unplugged for months doubled the annual emissions for the Los Angeles basin.

Robert Stavins is a professor of environmental economics at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School and has written extensively on California’s approach to climate change. The state’s new targets are “very aggressive, very ambitious,” he says. “The more you try to do, the more your marginal costs go up. It doesn’t come for free.”

To his credit, Brown doesn’t make it out to be easy. Speaking during the climate talks at the Petit Palais, an ornate museum built for the 1900 World Fair, he was particularly blunt about what his plan requires. “You need the coercive power of government,” he told the crowd. One of the reasons why California’s utilities already get so much of their power from renewables, he said, was because “they have no choice. The government said, ‘Do it, or you’re going to pay huge fines.'” Brown likes to upend the standard argument about government regulation gumming up innovation. To him, it’s the opposite: Regulations push businesses to try new things.

Few American politicians would have the pluck to declare this publicly. Yet Brown has a lot of advantages: He is free from the burden of reelection and for a long time had a supermajority in the Legislature, allowing him to shove through regulations that would have been dead in the water in any other state.

Brown also has the support of Mary Nichols, who sits at the helm of California’s Air Resources Board. No other agency has quite the same breadth of authority to craft policy — or the same extensive toolbox to enforce it — and that gives her sway over entire industries. In 2013, Time named Nichols one of the world’s 100 most influential people. In her many years at the Air Resources Board, she’s wielded her power to help usher in everything from three-way catalytic converters and smog tests to cleaner fuels and electric cars.

When I meet Nichols at a café in Los Angeles, she exhibits none of the swagger you often find in a powerful official. With close-cropped gray hair and wearing a turtleneck sweater, she orders a cup of tea and speaks so softly that I struggle to hear her over clinking dishes. Despite her unimposing presence, Nichols is supremely confident about the righteousness of her and Brown’s mission. “We made these arguments for a long time, but we weren’t too effective because there weren’t many economists on our side. Traditional economic models view all forms of regulation as costs without benefits.” She adds, “I think we’ve demonstrated that you can grow your economy and seriously slash global warming.” I ask if she looks to any other state or country as a model. “No, unfortunately, no,” she says. “We’re it.”

The Ocotillo Wind Farm is in Imperial Valley, near the Mexico border.Jamey Stillings

To understand how California came to stand alone, you have to look back more than a half century. Back then, long before “climate change” was a household term, California was choking on smog. A biochemist at Caltech, Arie Jan Haagen-Smit, had discovered that the problem stemmed from a reaction between vehicle exhaust and sunlight. Oil and car companies fought Haagen-Smit’s findings bitterly, but the smog problem became so dire that in 1967 Gov. Ronald Reagan signed the bill that created the Air Resources Board, and he appointed Haagen-Smit to head it. The same year, Congress passed the federal Air Quality Act, which gave California the power to set its own automobile emissions standards that could exceed those of the federal government.

But when the Clean Air Act in 1970 required every state to meet pollution standards within five years, California didn’t get a plan in place to do so. In 1972, Nichols, then a young environmental lawyer, sued the new Environmental Protection Agency to force it to hold California accountable. After Jerry Brown took office in 1975, he appointed Nichols to the Air Resources Board and made her its chief four years later.

As Nichols began fighting air pollution, Middle Eastern nations, angered at U.S. involvement in the Yom Kippur War, slapped an embargo on exports of oil and sent prices skyrocketing. Americans waited in long lines to fill their gas tanks, and shock waves rippled through the economy. Meanwhile, California’s population was burgeoning. In one study from the mid-’70s, the RAND Corporation estimated that the state would have to add at least 10 new nuclear reactors over the next 25 years to keep pace with the growing demand for energy.

Mother Jones

A physicist named Arthur Rosenfeld at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory became curious about how much energy people really consumed. To some of his colleagues, this seemed like a pedestrian topic for someone who’d studied under Enrico Fermi and distinguished himself in the field of particle physics. But Rosenfeld soon made a series of calculations that quieted them, recalls Ashok Gadgil, who was then a young graduate student of Rosenfeld’s and is now a senior scientist at the lab. Thanks to lax building codes, California used about as much energy to heat homes as Minnesota did, despite a 28-degree difference in average low temperatures, Gadgil says. Rosenfeld was the first to do the math showing how much you could slow electricity usage by setting in place energy standards for buildings and appliances. “It was a revelation,” says Gadgil.

Part of the problem was that the utilities — Pacific Gas & Electric, Southern California Edison, San Diego Gas & Electric — made more money if they sold people more electricity. PG&E “had people standing on street corners giving out 200-watt lightbulbs,” says Gadgil. Californians would take them home thinking they had just scored a freebie, screw them in, and double or triple the amount of power those lights were consuming.

To address the energy crisis, Reagan established the California Energy Commission in 1974. Soon after, Rosenfeld began to push the agency to create tighter building standards, and then to raise them every few years. He took on everything from the glazing of windows to the type of insulation used between the rafters. This enraged the utilities, which feared dwindling revenue. At one point a executive called the head of the lab to demand that Rosenfeld be fired.

But when Jerry Brown succeeded Reagan, he was captivated by Rosenfeld’s findings. So Rosenfeld, who would later sit on the Energy Commission, helped expand its purview to require that dishwashers, refrigerators, dryers, heaters, spa equipment — nearly everything in a Californian’s life — meet the toughest efficiency standards in the country. In 1999, Rosenfeld estimated that the changes the commission had set forth were saving $10 billion a year nationwide.

The agency has now said that by 2020, all new houses shall meet an exacting code called zero net energy — this means having features like thick insulation, tightly sealed windows and doors, and the capacity to generate all the power they need in a year via the sun or even wind. By 2030, all new commercial buildings will need to do the same.

These energy-saving requirements are just one indicator of how regulators have been able to leverage California’s huge market — 38 million customers — to influence national supply and manufacturing lines. Three years ago, the Energy Commission required that battery-charging systems, like the ones inside smartphones and laptops, be designed to suck less juice. Manufacturers balked because they didn’t want to bear the additional costs — about 50 cents per laptop. But the state insisted. The extra 50 cents, it turns out, saves the purchaser 18 times that cost in energy over the life of the product. That one change alone is estimated to save Californians $300 million a year in electricity bills. The Energy Commission figures that all its efficiency measures have slashed electric bills in California by $74 billion over the past 40 years.

As scientists saw increasing evidence of a warming planet, the focus on cutting smog and increasing efficiency shifted to curbing greenhouse gases. In 2002, Gov. Gray Davis signed the state’s first “renewables portfolio standard,” requiring utilities to get 20 percent of their power from renewable sources within 15 years. The standard sparked the development of a first generation of large solar installations, or “grid-scale” solar, the kind that now dot Kern County. But the rooftop solar business had stalled. “The market was backwoods hippies and Malibu millionaires,” recalls Bernadette Del Chiaro, now the executive director of the California Solar Energy Industries Association. In 2000, fewer than 400 California roofs were outfitted with solar panels.

“We had this chicken-and-egg problem,” says Del Chiaro. “Prices were high because demand was low. Demand was low because prices were high.” Arnold Schwarzenegger, during his bid to oust Davis via a recall, promised to jump-start the use of solar power. Schwarzenegger made it to office, but he couldn’t get his advisers to agree on a solar policy. To keep up the pressure, solar advocates crafted life-size cardboard cutouts of the governor from his Terminator movies and set them up across the state, so voters could pose for pictures next to them while holding signs that read, “Go Solar.”

Still, nothing budged. Schwarzenegger grew frustrated. At one point he convened his staff in the Ronald Reagan conference room, where he kept his Conan the Barbarian sword. When his advisers again began to bicker over details, Schwarzenegger’s face turned red and veins bulged from his neck. He pounded his fist on the long wood table and bellowed, “Don’t you understand? I want to get this fucking thing done.”

That thing turned out to be a carrot in the form of a $3.3 billion rebate program, which, as boring as that sounds, was monumental. At first, anyone who got rooftop solar received a handsome rebate — as much as $2.50 per watt. Combined with a federal tax credit, the rebate cut the cost of a typical home system in half. But the program was designed so that as more solar panels were installed across the state, the rebate money would be a little less generous.

This wasn’t meant to penalize future homeowners, but to incentivize industry. Jigar Shah was the founder of SunEdison, one of the early solar-installation companies. The rebate program, he explains, was really a social compact between the government and the industry. “It was, ‘We gave you money, now you go create jobs and bring down costs,'” he says. Solar installers began popping up all over the state, hiring more workers. The time it took to install a solar system went from four days to two, and sometimes just a few hours. And prices fell. Churches, schools, and even prisons started to go solar. Factories in China began ramping up their production of panels, creating an economy of scale — panel prices have dropped about 45 percent over the past decade. By the time the subsidies dried up, costs had fallen so much that it didn’t matter. “We turned solar into a real business. This was man-on-the-moon stuff,” says Shah.

The way California priced electricity helped too. Remember how used to hand out free high-wattage lightbulbs to get people to use more power? Now utilities are required to use a tiered electricity-pricing system. The more power you consume, the higher your rate. This can mean that for people who live in the desert and need to run an air conditioner half the year, affordable solar can be a godsend. Bakersfield, where summertime temperatures often climb past 100 degrees, has twice as many solar rooftops as San Francisco, despite being less than half the size.

But what the $3 billion really did was give the state a new industry — and a lot of new jobs.

In 2006, the release of the documentary An Inconvenient Truth planted the issue of global warming firmly in the California consciousness. With that momentum, the head of the Assembly, Fabian Nuñez, was able to pass the sweeping Global Warming Solutions Act that mandated the state shrink its greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by 2020. Republican New York Gov. George Pataki flew in to attend the ceremony (the term “climate change” wasn’t yet anathema in Republican politics) and Britain’s prime minister, Tony Blair, was patched in via a video link. Schwarzenegger boasted, “We will begin a bold new era of environmental protection here in California that will change the course of history.”

The act handed the Air Resources Board an arsenal of new powers, and Schwarzenegger wanted an ace to run the organization. Mary Nichols had been out of that job for 24 years, and she was a Democrat, but Schwarzenegger was adamant: “Mary was quite simply the best person for the job,” he told Bloomberg Business.

Her agency was charged with drawing the map for how the state would decarbonize its economy. It hired new staff to create an inventory of where all the emissions in the state were coming from. It wrote rules for everything from hair spray to methane escaping from landfills. It levied fines for businesses that didn’t comply and established new regulations for those that did. And most importantly, it set up a cap-and-trade carbon market, through which California’s major industrial players all buy or sell carbon credits — generating $3.5 billion in revenue for the state so far. In January last year, cap and trade expanded to include emissions from automobiles, which means companies that refine and sell gasoline must account for those emissions as well, making the system the most comprehensive of its kind in the world.

No business has felt the force of Nichols’ power as much as the automobile industry. The board has steadily ratcheted up fuel efficiency standards, surpassing federal standards, for cars and trucks. Around 2007, Nichols began to tell automakers that gasoline efficiency wasn’t enough — they would have to roll out new, fully electric models or other zero-emission vehicles. Manufacturers from Japan to Detroit rushed to build the cars Nichols demanded. And she upped the ante again: By 2025, fully 16 percent of all new vehicles sold in the state would have to be zero-emission. Not long ago, though, the board noticed that gas-powered cars coming off the assembly lines are pretty durable, which means they could be on the road longer. That, of course, would make it tougher for California to meet its emissions targets, so Nichols has made noise about hitting an even more ambitious mark: In 15 years, she wants new car buyers to only be able to shop for zero-emission vehicles.

That seems ambitious, crazy even. After all, the first time California tried to put electric cars on the roads, in the ’90s, manufacturers balked at the high cost of the technology, and the Air Resources Board had to back off its goals. But this time around, the technology has improved, and Nichols isn’t backing down. Today, every major manufacturer builds an electric car. Some, like Nissan, which builds the Leaf, hail them as a cornerstone of their brand. “You could say Mary largely created the market for zero-emission vehicles,” says professor Daniel Sperling, director of the University of California-Davis’ Institute of Transportation Studies and a member of the Air Resources Board.

In 2009, Matthew E. Kahn, who teaches environmental economics at the University of Southern California, was one of several economists who claimed California’s cap-and-trade program could cause energy-intensive industries to flee. Those that couldn’t bolt, such as food processors tied to local farms, would be forced to raise prices on citrus, nuts, or tomatoes, he predicted. Today, Kahn admits the costs for businesses were lower than he ever imagined. He now believes the impact on jobs was minimal, in part because heavy polluters, like steelmakers, had already left the state. But he also credits Nichols with having crafted the carbon market so it achieved the state’s goals with minimal costs. “The optimists have won the day,” he says.

Along with big rebate programs, the “coercive power of government” helped push cash into the development of new energy sources, so the utilities found themselves ahead of the deadline to get 20 percent of their power from renewables. But that created a problem. One very sunny Sunday in April 2014, officials had to cut off more than 1,100 megawatts’ worth of solar and wind power — almost enough to supply all the houses in the city of Fresno — for about 90 minutes because the grid was overflowing with electricity. Naysayers worried the state had reached its absorption limits for renewables and that the grid could fry. As a fix, the state expanded the utilities’ ability to trade power with neighboring states on what is called the energy imbalance market. When California generates too much solar power, the utilities can now sell it at 15-minute or even five-minute increments to Washington or Oregon right away (or buy power when the supply has an unexpected dip).

A number of tech companies, however, started looking at better matching supply to demand. First they turned to “demand response” systems, whereby major energy customers can ratchet down their use as needed. Johnson Controls Inc., a Fortune 500 maker of thermostats, batteries, and other products, runs a demand response program in California with more than 100 customers. When a utility realizes it won’t have enough power — when air conditioners are cranking — it sends a signal to Johnson Controls, which figures out which customers can scale back. That may mean cutting the power to a field of oil wells, or getting the city of Fullerton to dial back on its lighting at city hall. Companies love it because they get paid by the utility when they turn the power off. “I literally send customers checks,” says Johnson Control’s Terrill Laughton. Architects are now designing office buildings with built-in controls that can automatically turn off a bank of elevators or a cooling system when a utility calls.

“We can really transform the grid for the 21st century,” says Raghu Belur, the cofounder of Enphase, based in Petaluma, north of San Francisco. His company is connecting solar panels, software, and a powerful in-home battery to create, he says, “an energy management system.” If the panels produce power the home doesn’t need, the software detects whether it’s better to sell the excess to the grid or store it for use later. “It turbocharges the solar system,” explains Belur. His company will soon sell the system in Australia. But the hurdle is the price of the battery, which is still too expensive to make it practical for most homeowners.

Peter Rive, a cofounder of SolarCity, one of the nation’s largest installers of solar panels, insists battery prices are about to tumble — and transform California’s energy market. Rive’s certainty stems in part from the massive investment that Elon Musk (who happens to be Rive’s cousin and SolarCity’s chair) is making in batteries for cars and homes. Right now Musk’s company Tesla advertises one battery, the Powerwall, that’s big enough to handle the energy needs of a standard home during the evening. But it can still cost more than $4,000, including installation. Tesla claims it can fix that problem via economies of scale when it completes a battery-making “gigafactory” in Nevada.

Rive believes that in a few years home batteries will be commonplace and electricity will be part of the sharing economy, like Uber and Airbnb. When a utility needs extra electricity, it will be able to call on the battery in your home to power your neighbor’s washing machine, and it will pay you for the power you’re providing. According to Rive, this setup “looks somewhat imminent.” He gives it three years. It’s a neat and tidy solution, and full of the usual hubris of Silicon Valley. It is also the kind of innovation Brown is banking on to achieve his goals.

Almost every week a foreign delegation passes through Sacramento to meet California’s energy leaders. Recently, officials from China, India, South Africa, Mexico, and even Germany have all visited. Tatiana Molina was part of a delegation of Chilean officials and businesspeople who came last October. They met with utilities, toured the Tesla headquarters, and listened to presentations from government administrators. She was impressed. Then again, she was also skeptical. “You cannot take a California model and paste it in Chile,” she said.

Others warn that California will have trouble keeping up the pace without inflicting damage on its economy. “What [California] can certainly not do,” says Stavins, the Harvard economist, “is ramp up its policies at no cost. To think that it can, that’s just naive.” Gino DiCaro of the California Manufacturers and Technology Association says, “Everyone knows it’s going to be more costly to operate in California — that’s just a given. But the costs are mounting and no one knows where they will end.”

It is also sobering that the world’s other great experiment in greenhouse gas reduction, Germany, has stumbled recently. In the early 2000s, Germany began a massive effort called Energiewende, or “energy transition.” The country guaranteed that anyone who installed solar or wind panels could sell the power at a high fixed rate, and investors piled in. But the rate was so generous that Germany had to pass the costs onto its consumers, raising bills by about $220 a year per household. When the country also began to shutter its nuclear plants, utilities turned to the cheapest source of new power available: carbon-heavy lignite coal. Germany is now burning more coal than it did five years ago, and during 2012 and 2013 its greenhouse gas emissions actually increased. (They are now falling again.)

To make matters worse, Europe’s cap-and-trade system, responsible for limiting emissions across the continent, has been beset by fraud, as phony carbon credits from Russia and Ukraine have flooded the market. That has helped drive down the cost of carbon. For much of the last year it hovered around 7 euros, or about 35 percent cheaper than the price of carbon in California, almost wiping out incentives not to pollute.

Brown also has strong forces arrayed against him. The utilities have started to flex their muscles, pushing back against the rates they pay solar customers for the power they send to the grid. And last year, the oil industry lobby led an unprecedented $11 million campaign against measures including a component of SB 350, the landmark law that requires California to get half its electricity from renewables in the next 15 years. The lobby singled out the Air Resources Board and its “unelected bureaucrats,” warning that the bill’s provisions for cutting petroleum use in half by 2030 would lead to sky-high gas prices. The bill passed, but the oil companies got the petroleum mandate stripped out at the last minute by aiming hard at legislators from the Central Valley.

Brown admitted partial defeat during a press conference at the state Capitol: “Oil has won the skirmish. But they’ve lost the bigger battle because I am more determined than ever.” He made that quite clear when he stated that the Air Resources Board has all the power that it needs to cut petroleum use, and “it will continue to exercise that power, certainly as long as I’m governor.” He added, “Through the regulations on low-carbon fuel, we’ll take another step, and we’ll continue to take steps.”

“Who opposes any of our work on climate? There is no question that everywhere you turn it all goes back to the oil industry,” says Nichols.

The oil industry does loom large over her biggest task ahead. The transportation sector accounts for 37 percent of California’s greenhouse gas emissions. Just overhauling the freight rail system, she says, “will require massive new investment, and no one really knows where it is going to come from.” Despite a $2,500 rebate that has been dangling out there for six years, only about 175,000 cars in the state are electric — which means that to reach her ultimate goal, Nichols has to get close to 1.5 million zero-emission cars on the road in the next decade. She concedes that the carrots she’s had in place for some time, such as allowing electric vehicles to cruise carpool lanes, won’t be as effective going forward because those “lanes are not infinitely stuffable.” Like Brown, though, she continues to optimistically push ahead: “The only clash is over how much of an incentive it’s going to take to get these [electric vehicles] into consumers’ hands.”

At the Paris climate summit, Brown and Schwarzenegger jaunted around together, available for photo ops. It was as if to say: Here are a Democrat and a Republican (with a face recognizable around the world), hand in hand, dedicated to the cause. Even Kern County’s Rep. Kevin McCarthy — a tireless advocate for the oil business — has become a booster for the solar industry.

But here’s a key bit of context for all of the state’s efforts. Even if the state succeeds in slashing carbon levels, it would still only result in a blip in combating climate change. California is the world’s eighth-largest economy but accounts for only about 1 percent of global emissions. That, says Nichols, is exactly the point: to set an example. “We never thought that what we did in California was actually going to solve the problem of global warming,” she says. “But we thought we could demonstrate that you could.”