This story was originally published by Mother Jones and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

On Wednesday afternoon at the massive global climate summit in Paris, diplomats unveiled a new draft of the document they hope will save the world from global warming. After a week and a half of chipping away at the agreement, it’s considerably shorter — in fact, it’s about half the length it was just a couple of days ago. That’s a good sign that some points of contention are getting resolved, and that the prospects for an agreed-upon final draft are better than ever. Word around the campfire here is that the conference could wrap up on time — by the end of Friday — which would be virtually unprecedented in the 20-year history of global climate talks.

Apparently the latest draft of #COP21 agreement, just released, has ~75% fewer brackets (i.e., undecided questions). Progress!

— Tim McDonnell (@timmcdonnell) December 9, 2015

The new draft dropped just minutes after Secretary of State John Kerry gave his strongest speech in Paris so far, telling world leaders that the United States wants to get even more ambitious over the next couple of days. He said that the United States would join the European Union and dozens of developing nations in the “High Ambition Coalition,” a group that has emerged since the weekend and hopes to achieve many of the key goals sought by climate activists.

To that end, Kerry also said the United States will double the amount of cash it makes available to vulnerable countries that are already hit hard by climate change impacts. The number is still pretty small — just $861 million by 2020 — but it’s likely to be the last olive branch the United States extends as the talks approach their conclusion and Republicans in Congress continue to hammer President Barack Obama’s climate agenda.

“The situation demands — and this moment demands — that we do not leave Paris without an ambitious, inclusive, and durable global climate agreement,” Kerry said. “Our aim can be nothing less than a steady transformation of the global economy.”

Whether the Paris accord will actually make that happen is still far from certain. Everyone here acknowledges that there’s no chance the agreement will limit global warming to 2 degrees C (3.6 degrees F), the threshold that world leaders agreed to at the last major summit in 2009. (Some players here, especially the small island nations, are adamant that even that amount is far too high.) Instead, the object of this document is to require countries to ramp up their climate goals over time, most likely every five years. That appears to be the best chance we have of staving off the worst impacts of climate change.

“Everything that happens in Paris should be an enabling mechanism for future ambition,” said Derek Walker, associate vice president of global climate at the Environmental Defense Fund. “Paris has to be a catalyst. It’s in no way, shape, or form a final chapter.”

At this stage, it seems highly likely that that kind of periodic review will take place. But there’s still a lot of ambiguity about what exactly that will look like. How will the international community actually enforce its climate goals? Could there be sanctions, independent investigative review boards, or some other system? In his statement, Kerry’s view on these questions was muddled.

“No one is forced to do more than what is possible,” he said. “There’s no punishment, no penalty, but there has to be oversight.” Even though each country’s individual greenhouse gas reduction targets won’t be legally binding, “that doesn’t mean a country can get away with doing nothing or next to nothing.”

Huh.

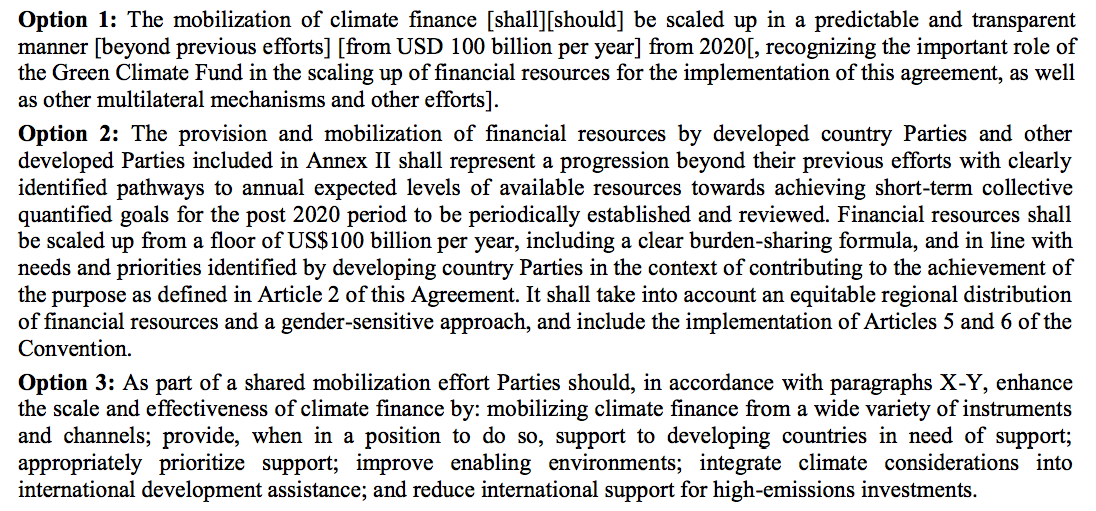

That’s just one of perhaps a dozen major questions that remain on the table for Kerry and his peers, said Jake Schmidt, director of the international program at the Natural Resources Defense Council. One of the most significant is climate finance, i.e., how wealthy countries will help poorer countries pay for climate change adaptation and clean energy development. Most negotiators agree that there needs to be an annual minimum of $100 billion raised collectively toward this end. But should that specific number be in the legally binding agreement? The U.S. delegation doesn’t want it to be, Schmidt said, because of the added pressure that could create on the country to cough up more cash. How, exactly, should the figure be increased over time, if at all? How, exactly, should it be divided between the United States, the European Union, and other wealthy players? Those questions remain on the table.

Three options for climate finance in the latest draft agreement.

Still, the atmosphere here is decidedly optimistic (if a bit bleary-eyed and frazzled). There appear to be no fights about basic negotiation procedure questions, which have bogged down previous summits. There appear to be no negotiators who think the whole document is totally unnecessary or a total sham. All the highest-ranking officials seem doggedly committed to not leaving Paris without some kind of agreement to take home.

Now they just have about 36 hours to finally agree on what it should say. This afternoon, French officials said negotiators should be prepared for consecutive all-nighters. The conference center is sprinkled with nap couches and is liberally stocked with baguette sandwiches, coffee, and wine.

Gotta love that the #COP21 cafeteria has both glasses and whole bottles of wine. Vive la France! pic.twitter.com/rS2kPouSqm

— Tim McDonnell (@timmcdonnell) December 9, 2015

“I think our sense is that almost everything we need for an ambitious agreement is still in play,” said Jennifer Morgan, director of global climate programs at the World Resources Institute. “But there is an immense amount of work to be done in the coming hours.”