Lakes of the Hudson Bay Lowlands, in northeast Canada, are showing evidence of abrupt change in one of the last Arctic regions of the world to have experienced global warming, according to Canadian research published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B journal.

The research team consisting of Kathleen Rühland, John Smol, and Neal Michelutti from Queen’s University Ontario, Andrew Paterson of Ontario’s Ministry of the Environment, and Bill Keller from the Laurentian University Ontario, retrieved sediment cores from lakes around the western shoreline of Hudson Bay and looked for changes in the microscopic algae that settle at the lake bottom after death.

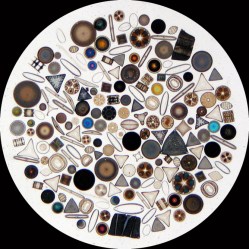

These algae, known as diatoms, are at the base of the food chain and are an important component of lake ecosystems. When they die and fall to the lake bed, they leave behind an environmental archive in the sediment layers that continually accumulate year after year. By examining the changes through time, researchers can trace the environmental history of the region.

WipeterDiatoms, tiny phytoplankton that hold clues to the climate of the past.

The Hudson Bay Lowlands were one of the last holdouts against the trend of global warming in the Arctic, but has in a very short period succumbed. In contrast to most of the Arctic, the lowlands maintained relatively stable temperatures until at least the mid-1990s. The region has been an Arctic refugium from warming due to the persistence of sea ice on Hudson Bay, the largest northern inland sea, that provides natural cooling.

Previous paleolimnological work (the study of lake histories) in the region found that the biological communities of lakes around Hudson Bay had remained stable for hundreds of years — unlike the dramatic shifts in aquatic biota that were observed throughout most of the Arctic in response to warming.

But in only a couple of decades, air temperatures in the region have increased at a pace and magnitude that are exceptional — even by Arctic standards. Recent studies by climate researchers on Hudson Bay have been reporting reductions in sea ice that have seen the open-water period lengthen by about three weeks compared to the 1990s. The melting sea ice has accelerated the warming trend of the region, quickly creating a positive feedback response that has increased the warming yet further.

We found that, for the first time in over 200 years, the lakes are showing signs of climate change. The diatom records showed relatively stable and simple assemblages consisting of benthic (bottom dwelling) species throughout the record until the last two decades. At that point, there was a distinct shift to more diverse assemblages that now include open water diatoms. These diatom changes are very similar to those we have found in lakes and ponds throughout circumpolar regions in response to rising air temperatures and less ice. But despite arriving much later in the Hudson Bay Lowlands, the speed and magnitude of the warming taking place here is extraordinary.

Jason SheathPolar bears living without ice: not a happy bear.

The response of freshwater ecosystems to this very rapid and pronounced warming carries many implications for the future of this Arctic ecosystem.

It is home to the world’s southernmost population of polar bears, who depend upon permafrost and on sea ice on the bay for survival. In just two decades, the response to warming can be detected at both ends of the food chain, among primary producers at the bottom and polar bears at the top. The effects are felt even among humans, with extreme and unpredictable weather conditions now commonplace in the region making it more difficult for First Nations people follow their traditional fishing and hunting routes.

Our findings suggest that ecological tipping points have been crossed and that, sadly, we are witnessing the loss of Arctic ecosystems as we know them. The Hudson Bay Lowlands are the southern-most Arctic region in the world, and therefore on the front lines of rising temperatures. One of the world’s largest peatland areas, the lowlands are a significant reservoir of the world’s carbon. If global warming were to increase the release of that carbon into the atmosphere, the repercussions would be of worldwide importance.

![]()