As a summer pastime, griping about rising gas prices ranks right up there with backyard grilling. Summer 2012 was slated to be a nonstop kvetching session: In spring, experts were predicting we’d pay $4 a gallon by season’s end.

Instead, in a repeat of a now common summer experience, prices dropped. Americans were left to grouse about a jump to a national average of just $3.42 for the month of July.

Why do we get this so wrong so often? To answer that, you have to learn how gas prices really work.

Where’s the beef?

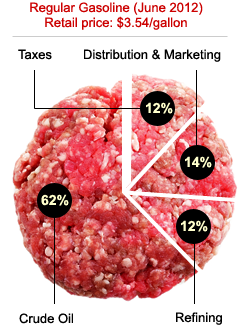

Think of gasoline as the burgers you might buy to toss on the grill at a backyard barbecue. Just as the cost of meat plays a huge role in determining how much you have to pay for patties at the market, the price of crude oil largely dictates what we pay at the pump.

Crude oil accounts fro roughly two-thirds of the price of gasoline. (Photo by Shutterstock.)

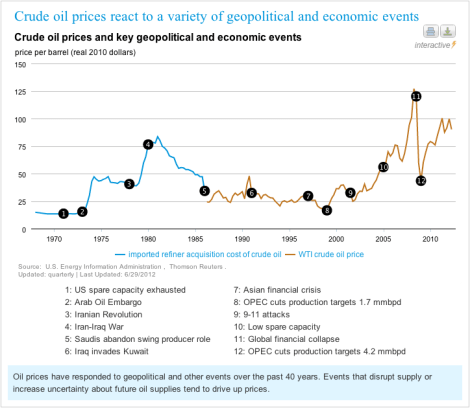

And here’s the thing: Crude oil, which is traded on global markets, roller-coasters along with the world economy. Global events knock prices around: wars and elections, economic crises like the one in the Euro zone, sanctions imposed on Iran’s oil exports, natural disasters like Hurricane Katrina.

As a result, “There’s no silver-bullet solution to immediately lower prices,” says Avery Ash, manager of regulatory affairs for AAA, which has tracked retail gas prices since 2000.

Here’s a handy chart that shows how crude oil prices have spiked and dipped in response to all kinds of disturbances in the force. (Note that “the president waved his magic wand” is not among them.)

Supply and dehammed

Much of what influences crude oil and gasoline prices is simple supply and demand. To return to our backyard barbecue analogy, if you have hordes of hungry guests and an inadequate supply of burgers, you can imagine people valuing them much more highly — even, heaven forbid, fighting over them. Cook up too many burgers, and the value goes down.

In terms of oil supply, production here at home doesn’t have much of an impact. Historical data does not support the notion that increased U.S. domestic oil production begets lower gas prices. It’s not like we get to keep all the oil we pump here – again, it’s a global market. And although it is conceivable that U.S. production could bump up the global oil supply, and thereby contribute to lower prices, “The amount of oil we’re producing is limited when you start talking about it at a global level,” Ash says.

In 2010, members of OPEC had more than 70 percent of the world’s proven oil preserves and produced more than 40 percent of the global oil supply.

If anyone has an oil spigot ready to turn, it’s the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, commonly known as OPEC. Member countries export 60 percent of all petroleum traded internationally. OPEC’s decisions about how much to supply, and the member countries’ ability and willingness to deliver (unhindered by trade embargoes, warfare, terrorist acts, political instability, and so on) are key factors influencing the price of oil on world markets.

So our barbecue is more like a potluck. But what began as a small family gathering is starting to look like a block party. That Chinese family that just moved in down the street just arrived, and they’re really hungry. Meanwhile, some of the diehard guests are trying to slim down.

Translation: Although the United States is still the largest consumer of oil, efficiency improvements are helping to reduce overall consumption. Meanwhile, nearly half of the growth in oil demand worldwide over the next five years is expected to come from China.

The meat grinder

Of course, many other factors can upend the picnic table, as it were. Burgers don’t come ready to eat; you have to grill them. And if your grill is anything like an oil refinery (where crude oil becomes gasoline), it requires a lot of maintenance. That can disrupt supply, and unless you’ve stockpiled a bunch of pre-cooked burgers in advance or can have a fresh batch delivered, it’s possible you’ll have a shortage.

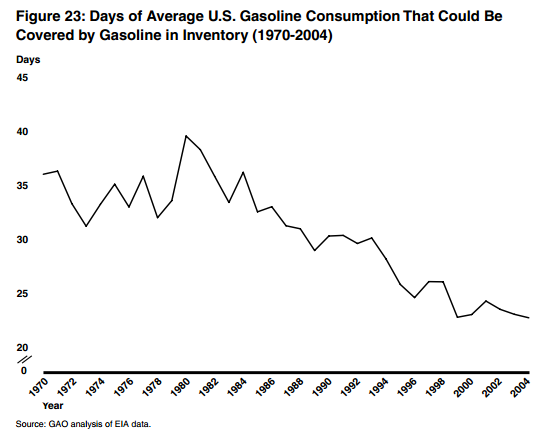

Fuel stockpiles have declined steadily in recent years. (From the GAO report “Motor Fuels: Understanding the Factors that Influence the Retail Price of Gasoline.”) Click to embiggen.

Similarly, to meet gasoline demand, U.S. refiners can draw from fuel stockpiles or import more from abroad. Imports can take weeks to arrive, however, and maintaining stockpiles is costly, so U.S. oil companies have opted to keep less and less gas on hand over the last 30 years, leaving little cushion against price spikes in the event of an outage.

There are other reserves, of course. In response to the 1970s oil embargo, the United States government set up a stockpile of crude oil called the Strategic Petroleum Reserve — and in times of crisis, someone’s always demanding that the federal government ease the oil shortage, and maybe cushion a gas price hike, by selling some of the reserved oil, which it has done on several occasions now. The reserve is relatively small, however — with a total capacity of 727 million barrels, enough to last only about three months if uncorked.

Complicating matters further is the fact that there are many types of gasoline. Some states require a special summer-grade gas to help with smog-fighting efforts, and not every refinery produces the stuff. Inventories fall especially low in the springtime as these refineries prepare to switch from winter-grade to more-expensive summer-grade fuel.

And hovering around this whole shindig is a group of poker players who place bets on the wholesale prices for the meat and the burgers and sides like corn. (Ethanol typically makes up 10 percent of gasoline sold in U.S. gas stations, and most of it is made from corn, so go with us on this one.) As a result of these “futures” gamblers, who trade in markets like the New York Mercantile Exchange and the International Petroleum Exchange of London, “even a rumor” about an extended refinery outage “can trigger higher prices … because of fears of a potential supply shortage,” according to a 2005 report [PDF] from the Government Accountability Office.

Even drought can influence gas prices by way of financial markets. Recent droughts in the Midwest have driven up corn futures and ethanol prices such that four or five cents of the 17-cent hike seen in gas prices in July 2012 could be attributed to ethanol, according to AAA.

In any event, oil production everywhere is going to drop off, sooner or later. Experts disagree when we might reach “peak oil,” or the point at which we hit the maximum possible annual production rate for crude oil. But oil is a finite, non-renewable resource — it too shall pass.

Git along little dogies

So what can we expect for our great neighborhood barbecue? Relatively pricey burgers, occasional bickering between neighbors, hunger and difficult choices for the poorest guests, and grumbling from stick-in-the-mud uncles who always had plenty of cheap burgers and dammit, they expect a cheap burger.

Of course, forecasters have been wrong, time and again, about the direction and pacing of gas prices. An act of war or infrastructure failure or natural disaster can always pull the rug out from under the most well-founded predictions, at least in the short term. But there is some writing on the wall.

“We’ve maintained a national average between that three and four [dollar-per-gallon] mark since the end of 2010,” says Ash. “Even if we come down for a little while, $3 per gallon has really become the new normal.”

In both the short- and long-term, trends point to continued volatility, which can be particularly problematic for commuters. Our drives to work do not suddenly shrink if filling up costs $20 more than it used to, and alternative transport or fueling options don’t magically appear.

Over the long haul, of course, we’ll need to shrink our dependence on fossil fuels — not only because the supply will, some day, run out, but also because burning them puts the whole planet on the grill.