A couple months ago, I wrote about the tepid approach scientists insist on taking when communicating climate change dangers. They keep taking this undashing, New Jay Z #factsonly approach to their messaging instead of taking it back to the Old-Jay-Z and letting the song cry.

Others caught this, including Stephanie Bernhard, who’s written about climate for blogs like The New Inquiry and Salon, and called it out in her review of Kristin Ohlson’s book on “no-till farming,” The Soil Will Save Us, in the May 5 edition of the Los Angeles Review of Books. Here’s what she wrote:

Climate writers are actually doing a decent job at terrifying the public and convincing them that life as we know it will change dramatically. But a lot of people in this country are … paralyzed by the problem’s magnitude and complexity. And we are not doing a good job of convincing people and especially governments to take action. Maybe the missing link is a healthy dose of optimism, a reminder that plenty of solutions to the problem exist and that it is possible to deploy them.

Bernhard has a point here, but she makes a necessary pivot. What’s more important than wrangling over what works with climate change messaging is exploring what’s been working on the ground, in terms of actual solutions.

And plenty of solutions do exist — a lot of them found among communities that are too often ignored when discussing global warming problems. Environmental justice organizations have been working on these problems for ages as they figured out how to best protect communities of color and low income from environmental hazards, since government protections so often miss them. Their approaches are mostly in response to localized pollution problems, but they often have climate change impacts in mind.

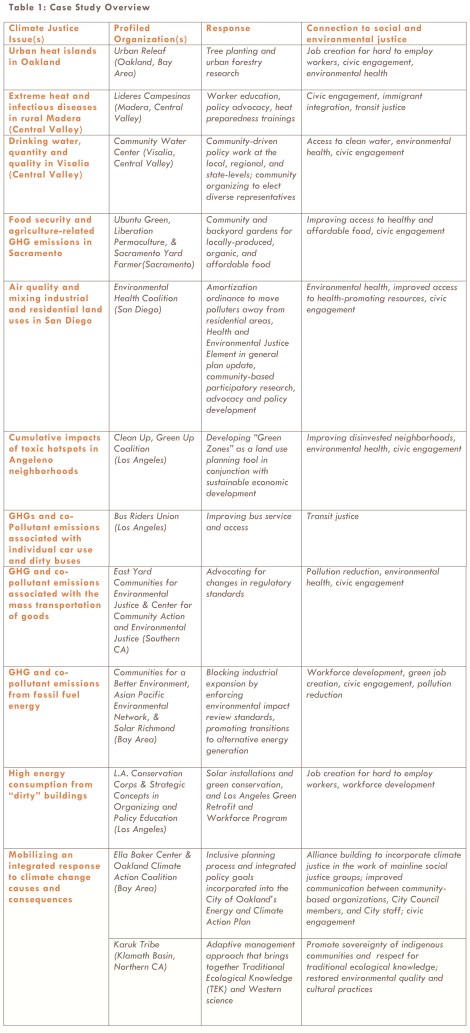

The University of Southern California’s Program for Environmental and Regional Equity listed many of these approaches in the 2012 report “Facing the Climate Gap.” The report details about a dozen cases across California where community-based environmental groups organized people from marginalized neighborhoods to address the environmental challenges facing their homes. All of the cases double as mitigation strategies for global warming.

These are not trivial cases. They’ve all produced demonstrable results in communities that quite frankly need to see immediate, positive changes, given that for decades they’ve lived with poor environmental protection that’s added up to poor living conditions. And they’ve produced these results despite major disagreements with state officials over climate change proposals like cap-and-trade, which many distrust as an adequate solution.

The report states that the cases model two things: “[F]irst, how you can be in conflict about policy and still work toward the broader common good, and second, how grassroots solutions can provide a new way to resolve our climate challenges and build a new consensus on the environment.”

Take for example the issue of extreme heat islands, which both IPCC reports and the U.S. National Climate Assessments agree is one of the worse climate hazards facing cities. The problem is that there are too many metal and impervious surfaces condensed in too close proximity in urban areas, which leads to overheating, not dissimilar to what happens with laptops when left on too long. If there are no cooling mechanisms around — a lack of air conditioning in poor communities, for example — then that overheating can lead to sickness and death.

The report points to one Oakland, Calif.-based organization called Urban Releaf, which serves its underserved city enclaves by putting residents to work planting trees, and lots of them. The group typically hires people who are part of what the government calls the “long-term unemployed,” those struggling to find employment due to recent imprisonment, and young people, who learn about forestry in the process. Since 1999, Urban Releaf has planted close to 16,000 trees, from Oakland to Richmond, providing shade and protection from harmful factory pollution for low-income communities, which happen to have the least tree coverage.

“Society and the prison system already know the specific areas where people are in most need,” Kemba Shakur, Urban Releaf’s executive director, says in the report. “They know cities like Oakland, Richmond, and L.A. bring the most inmates. So, to me, those should be the areas with the most services around education and forestry.”

Makes sense to me. And it’s a season-sweep in terms of winning: It helps people who are coping with the less-than-shady air problems of today, while creating the carbon-absorbers and shady leaf awnings needed for tomorrow; and, it also helps empower residents who too often feel powerless under such oppressive conditions. The report ties it all together nicely:

High unemployment rates can diminish neighborhood social networks and impair a community’s ability to collectively organize and solve problems, which in turn inhibit local-level resilience to extreme events, such heat waves and other weather changes that are expected to become even more frequent from the effects of climate change.

The report offers more triple-winning cases like these across California, including community gardens, “participatory research” (a.k.a. “citizen science”), and improved access to public transit. (See a complete list at the bottom of this post.) And these things are not just happening in the West Coast. After Hurricane Katrina, Mobile, Ala., resident Leevone Dubose led a mission to replant thousands of trees in her Trinity Gardens neighborhood, with the same multiplier effect in mind. Sharon Hanshaw is doing the same in Mississippi with Coastal Women for Change.

As Bernhard stated, there are solutions out there. This report gave some solid examples. Scalability is, of course, always a challenge, but these communities deserve a shot. They can’t wait for debates around climate change communication to get resolved. They need relief today.

Click to embiggen: