By 2080, Russia might witness a vast mammalian invasion, as sub-arctic European animals flee global warming and adapt to a thawing tundra. New textbooks may need to accommodate never-before-seen communities of species as climate change pits predator against predator beyond the Russian steppe. That’s what a group of Swedish researchers predict in a new climate change study published in the journal, PloS One.

“North Western Russia will be some kind of hotspot of species richness,” said Christer Nilsson, an ecology professor, via Skype from Umeå University in Sweden. “Species will be on the move and there will be new combinations of species.”

Red and fallow deer, wild boar, the Eurasian badger, rabbits, mice, and beavers will all be on the move as new tracts of habitable land open up.

John KentFallow deer, heading to Russia.

In a surprising twist, Nilsson and his team found that most species in the Barents Region, which includes the northern half of Norway, Sweden, Finland, and a big chunk of Northwestern Russia, will actually be favored by climate change. Forty-three out of the 61 animals studied will expand and shift their “ranges” — or habitats — mostly in a northeasterly direction, sometimes traveling hundreds of miles.

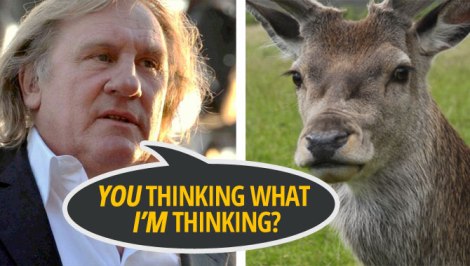

Anouschka R. Hof, Roland Jansson, Christer NilssonSuitable area for the tundra vole and its suitability for potential predators. “A” shows 2000 and “B” shows one 2080 scenario.

But no one can predict how all the animals will interact in their new, climate-changed world, and far from helping animals, climate change might force new, and deadly, interactions: “Predators might be in contact with new prey,” Nilsson said.

There might be tough times ahead for the poor little tundra vole, for example, which will need to elude more foxes, badgers, pine martens, stoats, weasels, polecats, and mink. That’s because right now, only 1 percent of the area Nilsson studied is suitable for three or more predators; by 2080, that could increase to nearly 40 percent. That means turf warfare for the mountain hare and the European hare, as both vie for similar habitats.

Two major caveats exist in the report. The findings assume that humans won’t — as we are so often wont to do — get in the way of the mass movement by fragmenting animals’ habitats. And the findings only apply to the “generalists” that can adapt to changing conditions. Those that require very specific habits — the “specialists,” such as the wolverine and the Siberian flying squirrel, are going to have a much tougher time in a warmed world.

Even so, the report found something encouraging: No extinctions predicted in the area surveyed. “We couldn’t find any evidence that any species will disappear, given the climate change predictions we’ve used,” Nilsson said. Nevertheless, vulnerability of those already threatened may increase due to the introduction of new competing or predatory species.

Naturally, a climate report that shows even a glimmer of hope can be latched onto and overblown. Fox News uses Nilsson’s study to declare the “poster animal” of the climate movement, the polar bear, totally OK: “Global Warming Helps Polar Bears.”

Polar bears are north of the area the researchers studied, and are not mentioned at all in the report.

This story was produced as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

This story was produced as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.