This story is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

The Environmental Protection Agency today released a long-awaited draft report on the impact of fracking on drinking water supplies. The analysis, which drew on peer-reviewed studies as well as state and federal databases, found that activities associated with fracking do “have the potential to impact drinking water resources.” But it concluded that in the United States, these impacts have been few and far between.

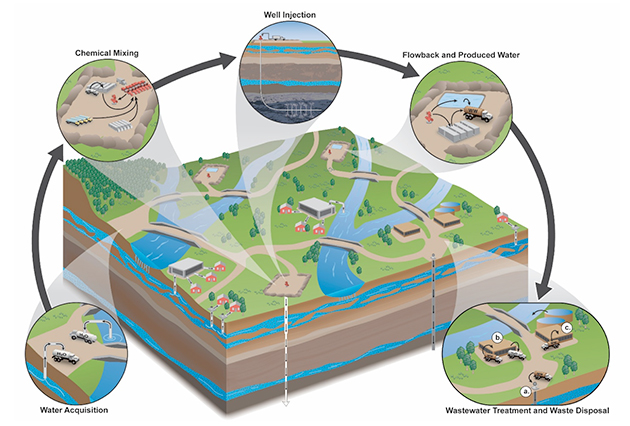

The report identifies several possible areas of concern, including: “water withdrawals in times of, or in areas with, low water availability; spills of hydraulic fracturing fluids and produced water; fracturing directly into underground drinking water resources; below ground migration of liquids and gases; and inadequate treatment and discharge of water.”

However, the report says, “We did not find evidence that these mechanisms have led to widespread, systemic impacts on drinking water resources.”

The report considered not only the hydraulic fracturing action itself, but all of the water-related steps necessary to drill, from acquiring water to disposing of it. Here’s an illustration from the report:

EPA

The report, which the Obama administration had hoped would provide a definitive answer to a core question about the controversial drilling technique, has been five years in the making. During that time, the EPA has faced numerous battles with the oil and gas industry to procure necessary data. Even before the report was released, some scientists voiced skepticism about its findings because of gaps in the data regarding what types of chemicals were present in water supplies prior to fracking activities.

As Inside Climate News explains:

For the study’s findings to be definitive, the EPA needed prospective, or baseline, studies. Scientists consider prospective water studies essential because they provide chemical snapshots of water immediately before and after fracking and then for a year or two afterward. This would be the most reliable way to determine whether oil and gas development contaminates surface water and nearby aquifers, and the findings could highlight industry practices that protect water. In other studies that found toxic chemicals or hydrocarbons in water wells, the industry argued that the substances were present before oil and gas development began.

Prospective studies were included in the EPA project’s final plan in 2010 and were still described as a possibility in a December 2012 progress report to Congress. But the EPA couldn’t legally force cooperation by oil and gas companies, almost all of which refused when the agency tried to persuade them.