This story was originally published by CityLab and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration. It is part two of a three-part series on the future of the San Joaquin Valley’s unincorporated communities. Read part one here.

In Matheny Tract, Calif., the sour odor of sewage is especially strong in the morning — and so is the irony that residents can’t connect to the system it represents.

The poor, unincorporated community of roughly 300 homes sits adjacent to the city of Tulare, population 61,000. A single, dusty field is all that separates Matheny Tract’s mostly African-American and Latino residents from Tulare’s recently expanded wastewater treatment plant. Though Tulare’s sewer system is more robust than ever, Matheny Tract residents must use septic tanks, since they are not part of the city. For a dense settlement, this spells trouble.

“People can’t always afford to pump out their tanks, so sometimes they overflow,” says Vance McKinney, a 59-year-old truck driver and community leader. “I’ve watched children jump over ponds of sewage to get to school in the morning.”

The leaching tanks are likely responsible for the fecal bacteria that’s been found in the shallow community wells from which Matheny Tract gets its water. Nitrates, probably from fertilizer runoff from surrounding farms, have also been an issue. Right now, the biggest problem is naturally occurring arsenic, exacerbated by an ever-shrinking volume of groundwater — partly a result of excessive pumping by farmers in the midst of California’s record-breaking drought.

Though residents can shower and clean with the water, it is undrinkable. For McKinney and his wife, that translates to spending an average of $160 on bottled water every month.

“We’re blessed to be able to afford it, and some of our neighbors are, too,” he says, taking a break from painting his house on a rare afternoon off from work. “But there are poor people out there who can’t.”

McKinney sits on the board of Pratt Mutual, the nonprofit group that operates Matheny Tract’s water system. Since the system’s arsenic levels exceed EPA limits, Pratt Mutual is legally obligated to resolve the issue. In 2009, facing deteriorating pipes, little money, and a lack of government oversight, Pratt Mutual decided to seek a water system consolidation with the city of Tulare.

This was logical, as it is for many low-income county subdivisions that sit on the fringes of bigger towns in the San Joaquin Valley. When one water system merges into another, more people pay to a single entity. That should mean the cost of water is lower for customers, and that there’s more revenue to maintain infrastructure. Managerial and technical headaches are eliminated for the smaller community. Risk of contamination is lowered.

Consolidation also makes sense from a geographical standpoint: When precious water supplies and infrastructure are available mere blocks away, why refuse to extend it to people in need?

CityLab

Caught between city and county governments, many of the San Joaquin Valley’s poor, unincorporated communities lack the most basic services. Government neglect, disenfranchisement, and poor land-use planning have helped shape these disparities, as I explored in the previous story in this series. A number of these towns have recently seen their wells go dry because of the drought. But for many more, water issues — especially contamination — are nothing new.

Because of the unprecedented drought, the gulfs in service between neighboring communities may finally begin to shrink. In June, California lawmakers passed a bill enabling the State Water Resources Control Board to mandate certain water systems to merge. The legislation was both a reaction to the plight of dried-out communities and a result of years of work on the part of clean drinking-water advocates.

Drought consolidation, as the bill is known, is flanked by the governor’s $1 billion drought emergency bond package, as well as state drinking-water revolving funds. Both funding sources can assist disadvantaged communities facing severe water problems — even those that haven’t been directly brought on by the drought.

But as with so much in the San Joaquin Valley’s poorest towns, consolidation has proven harder than it should be. Though there’s at least one success story, many cities want neither to annex nor extend services to low-income subdivisions, because the return on investment is so low. For too many thirsty people, old squabbles, inequitable planning, and deep-rooted prejudices put a fundamental need — water — even further out of reach.

Broken promises, ulterior motives

Matheny Tract was one of many pieces of far-flung county land settled by African-American farmworkers in the San Joaquin Valley during the mid-20th century. Migrating from the east, these workers and their families were often locked out of the Valley’s cities by high prices or, in many cases, overtly discriminatory real-estate practices. Land buyers — traveling salesman types — took advantage, snapping up large tracts and parceling them off to people with few other choices.

That’s why, at its founding, Matheny Tract sat a fair distance away from the city of Tulare. But Tulare has crept up to it over the years. When you look at maps of the city of Tulare’s annexation patterns going back to the 1960s, a pattern becomes clear.

[protected-iframe id=”7218752b8f0406618ece8e80201a3dec-5104299-94886244″ info=”//giphy.com/embed/3o85xmei0YKQ8C0c1O” width=”480″ height=”371″ frameborder=”0″ class=”giphy-embed” allowfullscreen=””]

City of Tulare annexation history and patterns of development. (Based on slides courtesy of California Rural Legal Assistance.)

“The city has pursued land that it can use to generate sales and property taxes,” says Ashley Werner, an attorney at the Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability, which provides legal assistance to Matheny Tract. “They’ve annexed for industrial use, residential use, commercial use, and everything else.” But Tulare has never annexed Matheny Tract or extended services to it.

So it is somewhat surprising that, when Matheny Tract asked Tulare to consider allowing them to consolidate with its water system back in 2009, the city said yes. A feasibility study was conducted and proved the connection workable. Matheny Tract applied for and obtained grant funding from the state’s Drinking Water Program to pay for new pipes to connect the community to the city.

In 2011, with funding in order, the city of Tulare, Tulare County, and Matheny Tract all jointly agreed that the city would merge its water system with Matheny Tract’s. That meant Pratt Mutual, the entity that manages Matheny Tract’s water system, would be totally dissolved. The city of Tulare would supply water, manage infrastructure, and bill and treat Matheny Tract customers as they would any others. Construction on the new water lines began.

But in June 2014, as workers were putting finishing touches on the pipes, plans changed: Tulare city officials announced that they were not, in fact, able to manage the consolidation. The well originally designated to serve Matheny Tract had been taken out of commission due to capacity concerns, and there was no back-up. Plus, while the new water lines were being laid in Matheny Tract, Tulare had approved connections on several hundred new homes in other developments. According to Tulare, all of this was now straining its ability to serve existing customers.

Tulare called for a hydrological study of its system, which, after several months, revealed that there was a pressure problem. Now, more than a year later, the city has said that that issue is nearly resolved. But it still won’t consolidate. Despite the agreement signed by the city, county, and community, Joseph Carlini, director of Public Works of the city of Tulare, now says there are jurisdictional issues.

“I can’t go in and service their pipes. I can’t go in and tell them how to use their water. It’s not city property. They’re unincorporated,” he says.

When Matheny Tract insisted that this curious backtracking violated the terms of their agreement, Tulare sued to change those terms. Now, instead of consolidating, the Tulare wants to sell water to Matheny Tract at wholesale and let Pratt Mutual continue to handle administration and maintenance. The suit also asks for the county to clarify the city’s jurisdiction. The county has called the city’s lawsuit “utterly without merit.” In June, Matheny Tract counter-sued to get what it agreed upon. Meanwhile, the community’s brand-new pipes are still sitting dry.

“If I had the skills to turn the water on myself, I would,” says McKinney, the Matheny Tract resident. “There are eight or nine people on [the city of Tulare’s water board]. Eight or nine people, and they can’t come together and decide they’re going to help us?”

CityLab

Carlini, Tulare’s public works director, believes the city is trying to help by offering the water at wholesale. “It’s not that we don’t want to provide service to them,” he says. “We just want some way of controlling stuff.”

But that’s not the same as accepting Matheny Tract residents as full-fledged customers. A July 2014 letter (obtained through Werner) from Tulare City Manager Don Dorman to a county resource analyst provides some insight on what the city is really after. Dorman, who did not respond to interview requests, opens the letter (a follow-up on a meeting) by suggesting that he puts Tulare’s own growth ahead of helping Matheny Tract:

We especially appreciated County representatives’ understanding that the City’s first priority must be to maintain its water system for existing City customers and for new City development commitments.

Besides the need to cover connections in these new developments, Dorman lists several other “structural issues” involved in consolidating with Matheny Tract. These include “cross-connection pollution potential”; dealing with “parties who illegally ‘hot-tap’ into the pipeline”; the need for “sheriff protection for billing enforcers”; and, namely, the “City General Plan”:

The new City General Plan is expected to clarify that the City has no intentions of growth and development into the area southwest of the railroad tracks on the southwest portion of the City. This policy is specifically designed to protect the operational integrity of the City’s key economic asset: its newly expanded state-of-the-art wastewater treatment plant. The City also intends to preserve an agricultural buffer around the plant for its operational needs … Growth into this area … is contrary to sound land use planning.

That “agricultural buffer” around the plant is effectively what surrounds Matheny Tract.

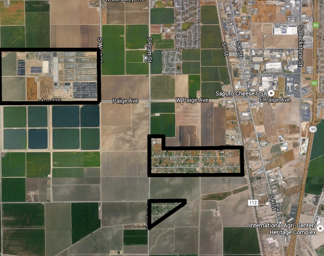

View of Tulare’s wastewater treatment plant

(outlined in upper left corner) and Matheny Tract

(outlined in lower right). The diagonal route right of

Matheny Tract is the railroad referred to by Dorman.Google Maps / CityLab

Now the State Water Resources Control Board has joined the fray. In mid-August, Tulare and Matheny Tract were the first in the state to be served with letters mandating that they consolidate water systems. As of August, they have six months to come up with a plan on their own. To help, the state will fund necessary infrastructure updates, provide technical assistance, and absolve all liabilities associated with Tulare inheriting Matheny’s system. But if the communities don’t come to an agreement on how to do this, the state will force one. Somehow.

“The hope is that our work is going to help people overcome their issues voluntarily,” says Karen Larsen, assistant deputy director of the State Water Resource Control Board’s Division of Drinking Water. “We have to figure out what the issues are. There are going to be situations where it’s never going to happen.”

McKinney is hopeful that Matheny Tract will get the water it is due, now that the state is involved. “The question is, when? It’s been six years,” he says.

In spite of all the conflict, and years of separation, McKinney believes Matheny Tract would be better off if it were annexed by the city. Some years ago, he tried to petition for annexation among other residents. But he says they were fearful of losing the freedoms they have on unincorporated land: low taxes, their ability to keep farm animals and commercial vehicles, and a certain “rural” identity.

McKinney, however, envisions what the community has to gain: lighting, curbs, gutters, sewers, and a sense of equality. “If we get annexed, praise that. If we stay an island, okay,” he says. “I just wanted to be treated fairly.”

“Those people won’t pay”

To Larsen’s point, there probably are places where consolidation will never happen. One of them might be Lanare — the Fresno County subdivision I focused on in the first story in this series. Much like Matheny Track, Lanare residents are predominantly African-American and Latino. Their water system is tainted with arsenic.

Riverdale, the somewhat wealthier, whiter town next door, is also unincorporated, and has also had its share of arsenic spikes. But with more financial and managerial capital, it has been able to resolve its water problems. Lanare and its legal advocates have asked Riverdale to consider consolidation on multiple occasions, even pleading with state lawmakers to intervene. But Riverdale has continually refused.

Merging with Lanare’s aging water system could be costly and full of liabilities. But legal advocates told me that the state, which currently holds Lanare’s water system in receivership, is planning to drill new wells for Lanare in addition to replacing the community’s aging pipes.

Between the new infrastructure, increased capacity, and all of the funds available through the state, consolidation could be a safe bet. But Lanare’s debts, incurred by a mismanaged, disused arsenic treatment plant the community took a risk on years back, seem to be too much of a threat.

“Consolidation is a terrible idea,” says Buddy Mendes, the county supervisor who oversees both communities, who lives in Riverdale. “They’d never be able to pay [Riverdale] back.” When I suggested that consolidation would offer greater economy of scale, he said, “For who? Not for Riverdale.”

Ronald Bass, operator of Riverdale’s public utility district, wouldn’t respond to requests for an interview. But he has stated his opposition to consolidation before: “Those people won’t pay.”

As in Matheny Tract, people in Lanare say Riverdale’s recalcitrance is about more than just cost.

“There’s always been a separation,” says Connie Hammond, a 73-year-old retiree who no longer lives in Lanare but returns to volunteer with the community. “It’s like, ‘you’re there, we’re here.’ They’re always kind of … looking down, actually.”

Ethel Myles has lived in Lanare for nearly all of her 68 years. Much as she wants the clean water, she’s not certain consolidation is the best option. “It would probably be beneficial,” she says. “But they wouldn’t ever accept us.”

CityLab

From my conversations with residents and officials, it’s hard to imagine Lanare customers ever being treated the same as Riverdale customers, even if they were both paying to a single district. Another option for Lanare would be for the state to appoint a private, investor-owned utility to manage it — though residents have said they don’t want that.

Mount Whitney Avenue, the same road that Lanare hinges on, serves as Riverdale’s main street. There are shops and restaurants, and on the morning that I visited, a Little League sign-up tent was set up on the sidewalk. I chatted with the people manning the tent about how the drought was affecting local businesses. Then I asked how Lanare was doing with water.

“Oh, them. They’ve got a checkered past,” said one man, a state corrections officer who asked that his name not be used. Though he wasn’t sure about Riverdale’s official reason for rejecting consolidation, he did say this about Lanare: “They’re always looking for a handout.”

A community wins

Change comes incrementally, and usually by force. But it can come. The story of Cameron Creek Colony is an example.

A square in a patchwork of walnut groves, the low-income, 100-home county subdivision has a rural feel — even though Farmersville, a city of 11,000, has partly grown up around it.

Resident Roger McGill remembers what is now unimaginable: when there was water in Cameron Creek. Standing on a front porch trimmed with wind chimes and spinners, the 69-year-old points beyond the houses across the street, toward the now-dry waterbody that gave his hometown its name. “You used to be able to take a boat out there,” he says. “The water was so high, it used to flood.”

For decades, Cameron Creek residents were self-reliant, using domestic wells with a clean supply. Then the drought came four years ago. No rainfall, no creek, and little by little, no groundwater.

“I could have never imagined this,” McGill says, surveying his dusty yard. It once had a lawn, shrubs, and flowers, he says. “Now it kind of looks like a junk pile.”

In the summer of 2014, wells in Cameron Creek began to go dry. The adjacent Farmersville water district, meanwhile, continued to serve their customers without issue.

Paul Boyer is mayor pro tempore of Farmersville. He’s also one of the directors of Self-Help Enterprises, a nonprofit that helps construct homes and make service connections for low-income families in the region. One August morning during my week in the San Joaquin Valley, he accompanied me around Cameron Creek.

Before the drought, Cameron Creek wanted nothing to do with a community water system, Boyer says. “But priorities change.”

Residents badly needed water. One option, which had been debated over the years, was to petition for Cameron Creek to be annexed into Farmersville, and thereby included in its water services. By and large, Cameron Creek residents still weren’t interested in giving up their unincorporated status, for the same reasons that many Matheny Tract residents aren’t.

But Farmersville could help Cameron Creek without annexing it, and Boyer’s liaison position helped them do that — in record time. Within months of the wells running dry, Farmersville secured state and federal grants to extend a water main to Cameron Creek. Residents who opted in paid a few hundred dollars to connect to the main, plus a small city hook-up fee. Less than a year later, most Cameron Creek households were customers of the Farmersville water district. They’re still outside municipal limits — an arrangement that pleases Farmersville officials, too.

“The city doesn’t want to be annexing an area where there’s not much tax base and a lot of need,” Boyer says. “It’s a win-win situation.”

Smart growth for small communities

In my previous story, we met Isabel Solorio, a housekeeper and community activist in Lanare. Like Vance McKinney in Matheny Tract, Solorio has hopes for her community beyond consolidation. “It’s fair to have dreams,” she says. “I want to keep working to have basic resources. Not luxuries, but basic needs: water, sidewalks, streetlights, and sewers. A park where our kids can play.”

Solorio’s Easter egg basket made from a water jug.CityLab

Solorio shows me pictures of how she’s been recycling her old plastic water jugs, which the state delivers to Lanare residents for free. Last spring, she sliced off the bottoms, turned them upside down, decorated them with construction paper, and filled them with candy. Poof: Easter-egg baskets for kids in Lanare.

It’s for the young people, Solorio says, that she really wants to see her community attract new development: New houses, new families, and a long-term future.

Her dream of growth might be compatible with what’s happening in the San Joaquin Valley. It’s predicted that by 2050, nearly 7 million people will live across its eight counties, about 50 percent more than do today. High-speed rail is supposed to help accommodate and shape new development in the region’s cities. “Smart growth” is often touted as a key component of the San Joaquin Valley’s future success.

But smart growth would seem to preclude places like Lanare and Matheny Tract, which have scarcely had a chance to grow at all. At the same time, sprawl continues, and new subdivisions keep popping up, far from city services. Resources — money and water — are limited. Existing communities are finding themselves competing against envisioned ones.

Driving back from Cameron Creek Colony to Self-Help Enterprises’ offices in the city of Visalia, I ask Boyer what he thinks about the future of towns like Cameron Creek Colony, Matheny Tract, and Lanare. Even with consolidation, can they be become truly sustainable? Will they grow with the Valley, or will they vanish with the water?

“I think you want to provide services to make these communities as livable as possible,” he says. “But not develop more of them.”

Next week, we’ll see how that’s going.