In March of this year, researchers at U.C. Santa Barbara and Columbia published a paper linking climate change and extreme drought to the Syrian Civil War. It wasn’t the first time that scientists and economists had connected the dots between climate and violent conflict. It wasn’t even the first time that scientists had connected the dots between climate and conflict in Syria.

“For Syria,” wrote the authors, “a country marked by poor governance and unsustainable agricultural and environmental policies, the drought had a catalytic effect, contributing to political unrest.” The central thesis is a daisy chain of cause and effect: Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s mismanagement of farm and fuel subsidies in the face of severe water shortages displaced an estimated 1.5 million Syrians, many of whom were the same farmers subsequently recruited into the Assad opposition. As the argument goes: If there had been no historically extreme drought, there would have been no civil war — at least not one beginning in 2011.

Of course, causality is a delicate beast. The link between climate change and the Syrian crisis is thus one of “threat multiplication” — of untimely, drastic amplification of a preexisting sociopolitical instability.

Now, a new independent report commissioned by the G7, the forum composed of the seven wealthiest developed countries and the E.U., argues that addressing the threat multiplier hypothesis needs to be a top foreign policy priority. The authors also contend that policymakers need to integrate their approaches to climate change adaptation, international development and resilience training, and peacebuilding.

Titled “A New Climate for Peace: Taking Action on Climate and Fragility Risks,” the report also analyzes several climate-fragility case studies, including the Syrian case, in order to help paint a picture of the global nature of the trends at play. The picture isn’t pretty.

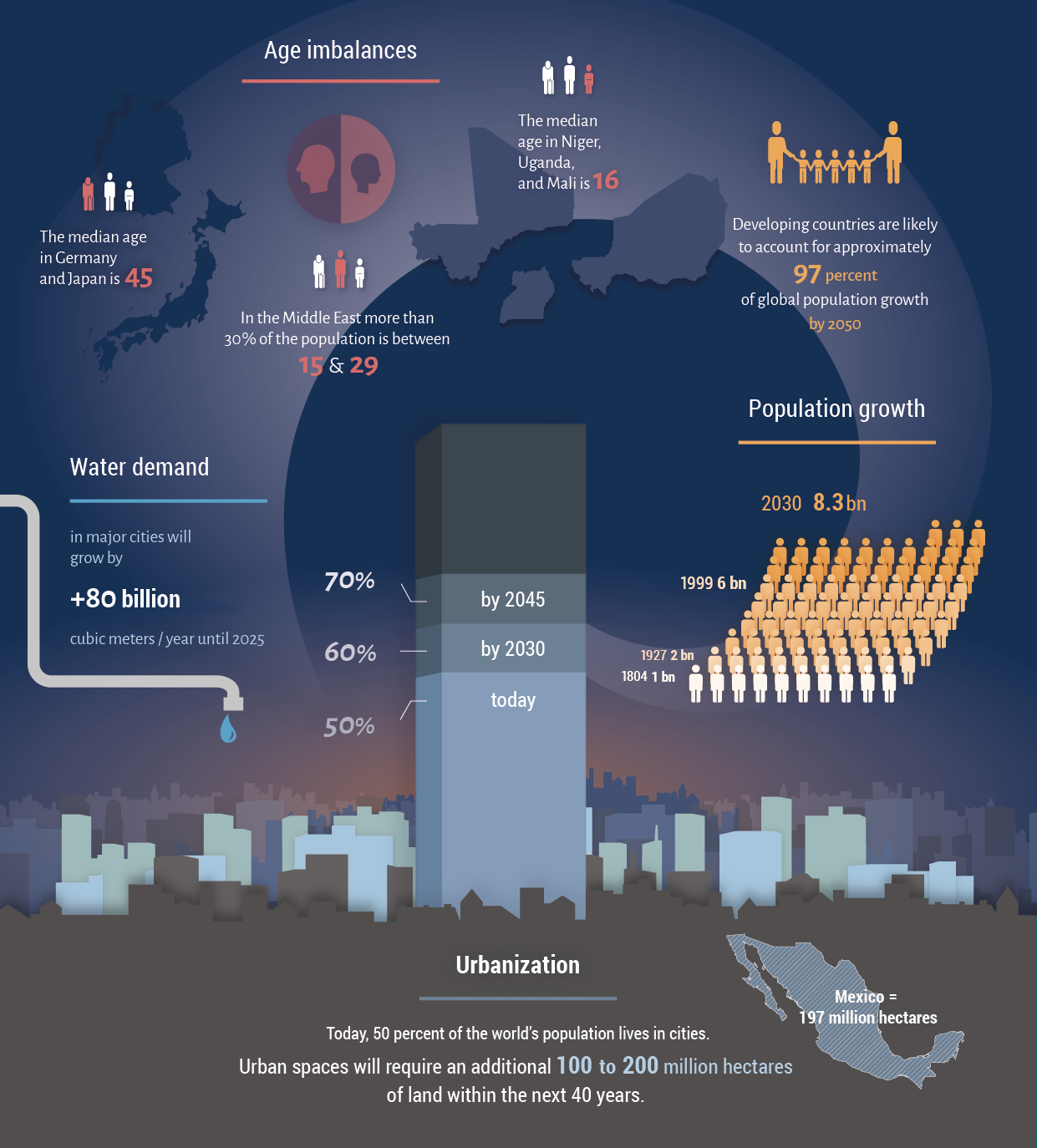

Here’s a map showing the nations where climate change is most likely to compound other security problems:

The authors identify seven “compound climate-fragility risks” that are likely to be amplified by anthropogenic climate change in the coming decades:

- competition for local resources

- disruption of livelihoods, which can lead to migration

- extreme weather events and disasters

- volatile food prices and problems with food availability

- management of water that crosses national borders

- sea-level rise and coastal degradation

- the unintended effects of climate policies, which may include “increased insecurity of land tenure, marginalization of minority groups, increased environmental degradation and loss of biodiversity, and accelerated climate change.”

It’s important to stress that these risks are not mutually exclusive. From the report:

These seven compound climate-fragility risks are not isolated from each other. They interact in complex ways, frustrating the development of effective responses at all levels. For example, transboundary water conflicts can disrupt local livelihoods and access to natural resources, while market instability and extreme weather events can impact global supply chains, with serious local repercussions. At the same time, local natural resource conflicts and livelihood insecurity are primarily local challenges, but they can have significant knock-on effects, such as increased migration, economic disruption, or social tensions, that can spur instability both locally and across a wider area.

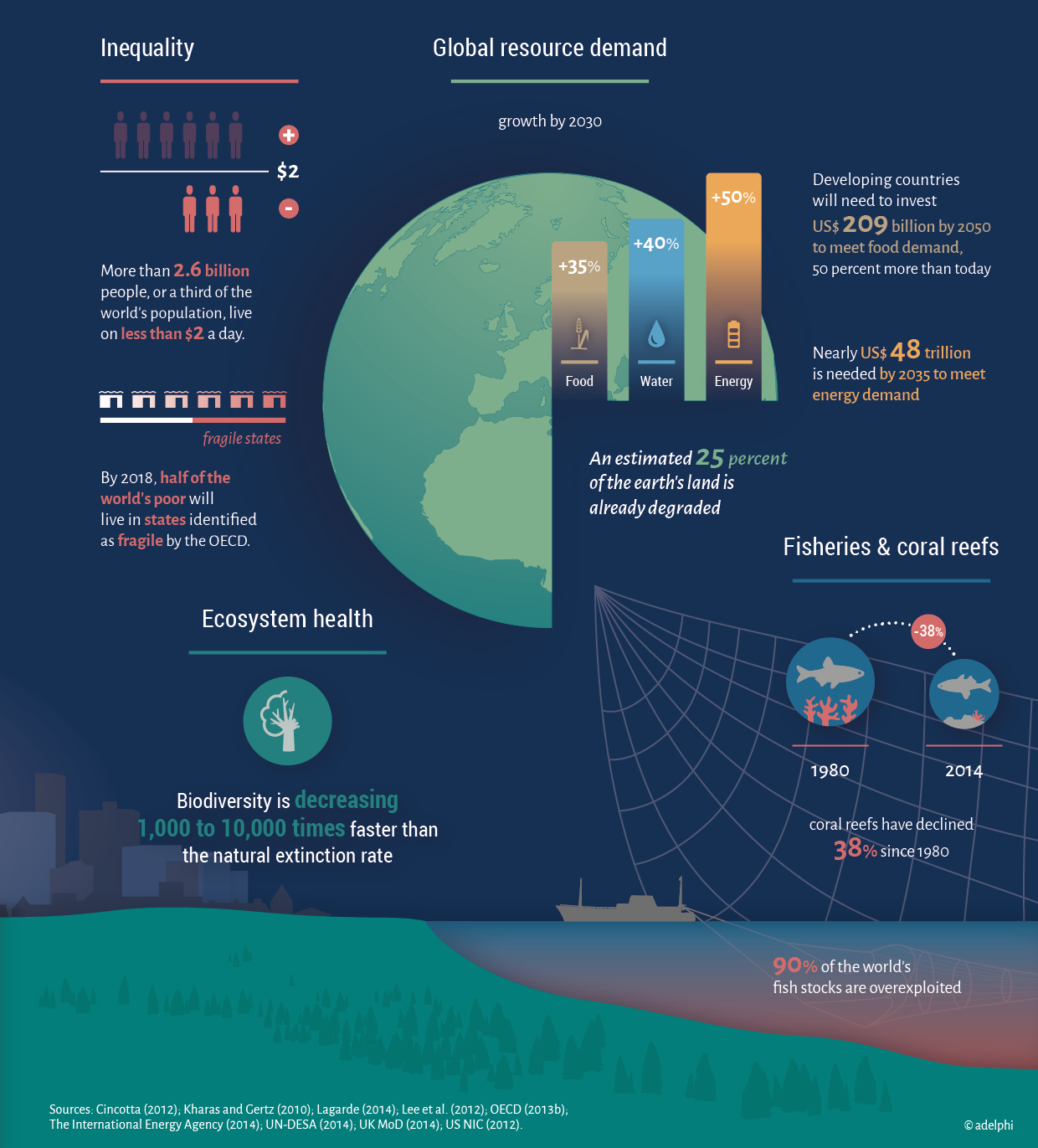

These pressures and shocks are likely to increase in the future, write the authors. A set of infographics highlights a handful of the underlying tensions:

The G7 report comes on the heels of a recent Department of Defense push to incorporate climate change considerations into its operations. Indeed, the DoD has been oddly progressive on the issue.

In his May 20 commencement address at the U.S. Coast Guard Academy, President Obama said that climate change “constitutes a serious threat to global security, an immediate risk to our national security.” It’s time for foreign policy officials to take that seriously, argue the authors of the New Climate for Peace report.

We may not ever know the precise degree to which climate change helped spur the Syrian Civil War, but we should do our best to remove the threat multipliers that could contribute to conflicts in other parts of the world. Imprecision is no excuse for inaction.