Nine climate activists are facing charges in New York state for an act of civil disobedience. One day in November, they blocked the entrance to a parking lot in Montrose, N.Y., where work is being done on a major natural gas pipeline expansion, the Algonquin Incremental Market (AIM) Project. Now they plan to defend themselves in court on the grounds that their actions were necessary to protect humanity from climate disruption. Consider it a form of self-defense.

The Montrose 9, as they’re calling themselves, are following in the footsteps of the Delta 5, a group activists who blocked an oil train in Washington state. Earlier this year, the Delta 5 became the first defendants to present at trial a so-called “necessity defense” related to climate change or fossil fuels. The judge in their case did not ultimately allow the jury to consider the necessity arguments when rendering a verdict, but the Delta 5 plan to use the defense again when they appeal their case to a higher court.

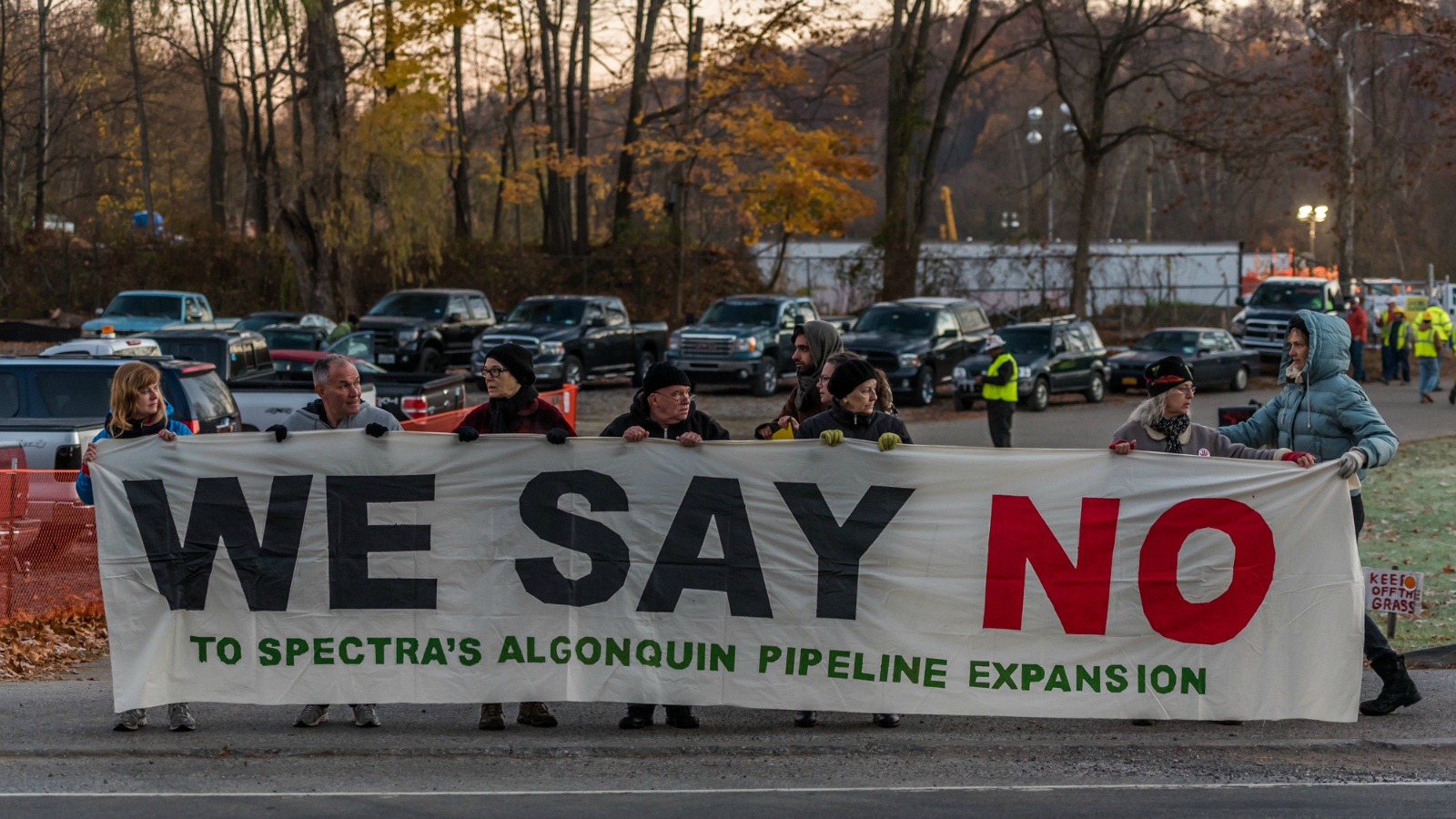

The Montrose 9 block Spectra Energy from working on its pipeline project. Erik McGregor

And now the Montrose 9 could become the second group to present a climate necessity defense in court. Their trial had originally been scheduled to start on Feb. 3, but it has been indefinitely delayed.

The AIM Project is an expansion of an existing Algonquin Gas Transmission Pipeline system, owned by Spectra Energy. The company wants to build a larger, more heavily pressurized pipeline that would allow it to carry natural gas from the fracking fields of Pennsylvania to New England, via Westchester County, just north of New York City. Spectra says this would serve gas-fired power plants in Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts, but activists believe the company’s ultimate goal is to connect with pipelines to Canada or export the gas overseas via liquefied natural gas terminals. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) has already approved the project, and rejected activists’ requests for a stay and a rehearing.

The Montrose 9 are far from the only ones trying to block or at least slow down the pipeline’s construction. Activists from communities in all four affected states — New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts — are taking action on every possible level. They’re calling on state governments to revoke construction permits. They’re pressuring local elected officials to express opposition to the pipeline expansion. They holding press conferences. They’re staging sit-ins.

And, because those tactics probably won’t succeed on their own, a number of the activists are turning to direct action, like the Montrose 9 did. In Rhode Island, for example, Fighting Against Natural Gas (FANG), a grassroots organization based in Providence, has sponsored a number of acts of civil disobedience to protest Spectra’s expansion of a compressor station alongside the pipeline in Burrillville, R.I. In May, FANG cofounder Sherrie Anne Andre sat in a nearby tree that was going to be cut down to make way for the project, stopping work for a day. In August, two FANG activists chained themselves to a fence outside the compressor station. In September, three FANG activists locked themselves to construction equipment at the station. Each time, they were forcibly removed by police and arrested. In December, FANG held a 100-person march to oppose the larger compression station and the whole AIM Project. “We’re trying to come up with any creative approach we can,” says FANG cofounder Nick Katkevich. Counterparts in Massachusetts and Connecticut are doing the same.

It’s no wonder that citizens along the pipeline route are up in arms. Living near a pipeline carries risks, and the bigger the pipeline, the bigger those risks. As ProPublica reported in 2012, “Since 1986, pipeline accidents have killed more than 500 people, injured over 4,000, and cost nearly seven billion dollars in property damages.” There are more than 2.5 million miles of fuel pipelines in the U.S., so that’s a relatively low accident rate. But no one wants to be the unlucky person in that statistic.

Activists are also worried that the pipeline project is so close to the Indian Point nuclear power plant, about 25 miles north of New York City. “The massive new pipeline, which is larger and higher pressure, will run 105 feet from critical infrastructure of the power plant,” says Courtney Williams, a cancer researcher at a pharmaceutical company who lives 400 feet from a section of the pipeline and became involved in opposing its expansion through a group of concerned residents called Stop Algonquin Pipeline Expansion (SAPE). Indian Point is already a major source of concern in the region, plagued as it is by safety problems. An accident or meltdown there could expose millions of people to radiation. It’s a ripe target for terrorists, and adding a big, high-pressure gas pipeline in its vicinity could make it even riper.

Spectra Energy says there is no cause for concern, pointing to its history of safely operating the existing, smaller pipeline. “Spectra Energy’s Algonquin Gas Transmission pipeline system has been operating safely in the area for more than 60 years providing clean, reliable, domestic natural gas to heat homes and businesses,” said company spokesperson Marylee Hanley, in an email to Grist. “Algonquin has existing pipelines that were installed in 1952 and 1968 across the Indian Point property and have operated safely without incident.”

Opponents are not reassured by that. For one thing, new pipelines are actually less safe than older ones. Pipelines built in the 2010s have been failing at about three times the rate of those built from the 1950s to the 2000s. Spectra’s own pipelines elsewhere have exploded. In Little Rock, Ark., a Spectra pipeline carrying natural gas ruptured in May. “It was frighteningly similar” to the AIM pipeline project, says Williams, noting that the busted pipeline was a backup line under the Arkansas River, just like how the current Spectra pipeline under the Hudson will serve as a backup to the new pipeline the company is building. “Spectra was completely unaware this had even happened,” Williams continued. “An angry tugboat captain reached out to the Coast Guard because a piece of the pipeline had landed on his boat and damaged it.” (You can read about the incident here.) Spectra did not respond to Grist’s questions about the Arkansas rupture and explosion.

And some worried residents contend that, even without a major blowout, pipelines chronically threaten neighbors’ health. Gas flows through a pipeline because it is pressurized. Sometimes, in what is called a “blowdown,” pipeline operators will release pressure because they don’t want to push gas through as quickly. When that happens, unrefined gas is released at compressor stations along the pipeline route. This gas is coming straight from the wells, and co-contaminants, such as volatile organic compounds like benzene and toluene, may still be present. The acute effects of exposure include nosebleeds, headaches, and breathing problems. There’s been only limited research on the long-term health effects, but many people who live near gas wells complain of chronic health problems such as fatigue and respiratory ailments. Williams argues that these health concerns are just as much of a worry as the possibility of an explosion. “There is a sensationalism about potential rupture because it’s catastrophic, but it will [also] be a catastrophe for folks having to breathe this stuff,” she says.

Activists argue that since New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo (D) banned fracking in New York state in 2014, precisely because of these kinds of health concerns, there shouldn’t be pipelines carrying fracked gas through the state either. “New York state has outlawed fracking because of health and safety issues,” says Kim Fraczek, one of the Montrose 9 and co-director of Sane Energy Project, an anti–fossil fuel group in New York. “We need to consider that the [gas] infrastructure is just as damaging to our health and safety just as much as the drilling is.”

All of the activists interviewed for this story also emphasize that their opposition isn’t just a question of immediate health and safety. It’s a broader concern about the biggest long-term threat to everyone’s health and safety: climate change. Why, they ask, are we building new fossil fuel infrastructure? Even as the U.S. is finally moving away from coal, why is it expanding its use of natural gas, which may be just as bad for the climate? Spectra’s AIM project “is a superhighway for fracked gas when we need to get off fossil fuels,” says Williams.

And so they are trying to throw sand in the gears of the fossil fuel economy, hoping to grind it to a halt. If nothing else, it will warn companies that the cost of investing in fossil fuel delivery has been raised. “We want to send a signal down the line that fossil fuel infrastructure projects will look like this from now on,” says Patrick Robbins, a spokesperson for Sane Energy Project.

In the absence of a rational, nationwide system for pricing the negative externalities of fossil fuels — including both climate change and the impact of conventional pollutants on nearby residents — direct action is one of the few ways of making polluters pay.