huangjiahuiLike solving a Rubik’s Cube, it’s going to be a long, ugly slog.

Climate change is a huge, knotty, incredibly difficult problem. The more you dig in and understand the science and politics of it, the more hopelessly vast and complex it can seem. What’s more, the public has not even begun to grapple with it; public discussions, especially in the U.S., remain polarized, shallow, and stupid.

Given this situation, it’s natural for climate hawks to yearn for a Grand Gesture, something that clearly announces our intention to Solve the Problem. They want a policy response as powerful as the threat, one that can power past all the fog and ignorance and greed.

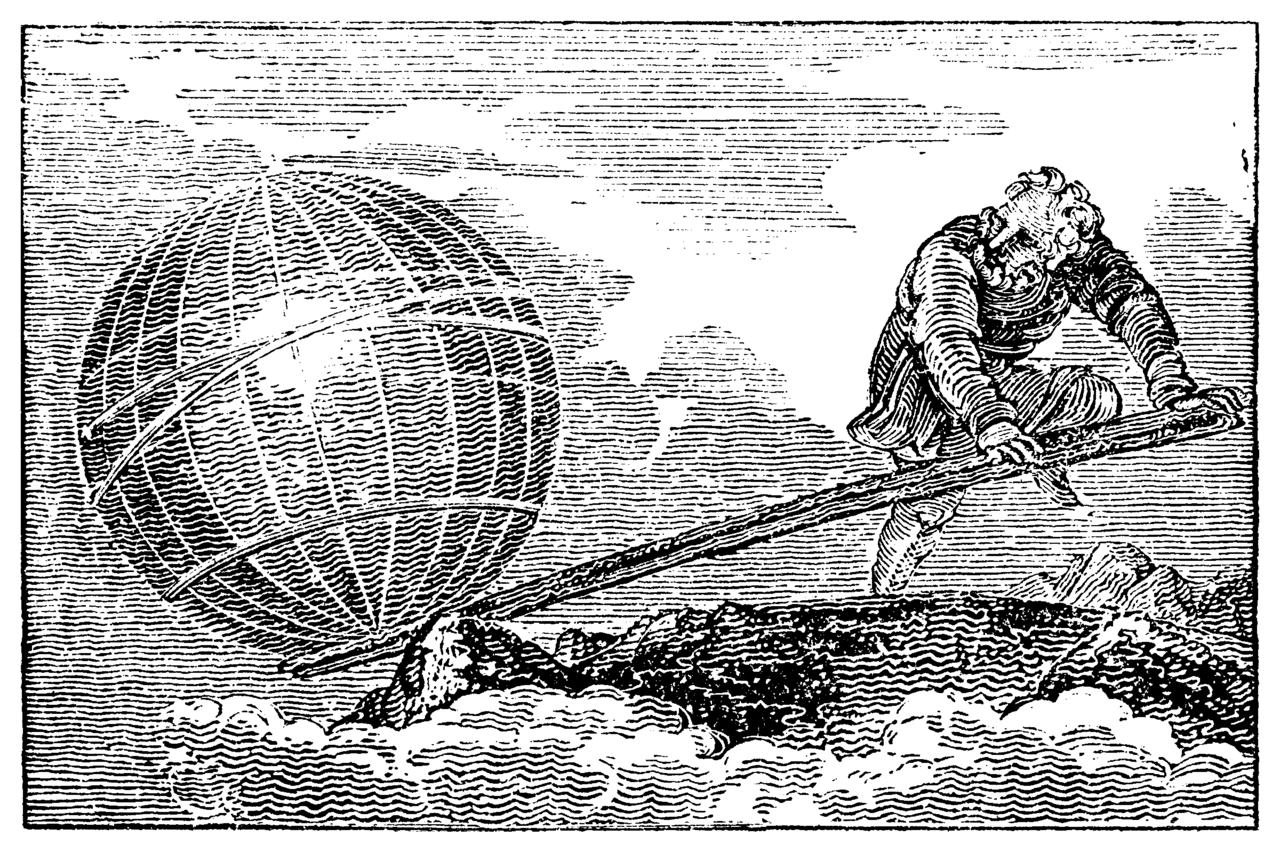

In short, they want Archimedes’ lever. “Give me a lever long enough and a fulcrum on which to place it,” said the great scientist, “and I shall move the world.” The pursuit of carbon targets by environmentalists and carbon taxes by economists both, I think, reflect this yearning.

Carbon targets

First, carbon targets. Over the years, I’ve become much more skeptical about targets as a goal of climate policy. The key insight here is that targets do not, in and of themselves, have any motive force. A target is not an emissions-reduction policy, any more than a weight-loss goal is a way to lose weight. A carbon target is a promise, a commitment to develop emissions-reduction policies.

But if a nation’s leaders believe that carbon-increasing policies are in their short-term interests, no target will stop them from pursuing those policies. Witness fledgling petrostate Canada getting ready to blow past its Kyoto targets. A target cannot force a nation (or state, or city) to act against its own perceived interests.

Furthermore, a target does not increase a nation’s capabilities. Reducing carbon requires new technologies, business models, and policies. Insofar as a nation’s access to those capabilities is limited, no amount of proclaiming and committing will make any difference. A carbon target is inert without the institutions, practices, and technologies necessary to achieve it.

That carbon reduction is primarily about national interests and capabilities is not my insight. I owe a debt to political scientist David Victor, whose work I wrote about here:

Above all, [Victor] says, climate campaigners must abandon their scientism and take emission-reduction targets off center stage. National leaders cannot credibly promise particular emission levels in the short- to mid-term. Emissions are determined by too many forces outside governmental control, including fossil-fuel prices, trade, and the pace of economic growth. The focus on targets is an invitation to empty grandstanding and lowest-common-denominator agreements. What leaders can credibly promise are policies, and policies, not numerical targets, should be at the center of climate accords, Victor argues.

Where I disagree with Victor and other target skeptics is that I still think national targets are worth pursuing. I think it was the right call to push for the Waxman-Markey bill and those who say it wasn’t worth passing, or that we’d be worse off if we’d passed it, are f’ing daft. The bill was a carbon target coupled with a set of overcautious policies (too many offsets, etc.). Having the target in statutory law could not have forced the development of stronger policies, but it would have been an incredible legal, political, and moral tool in the hands of those fighting for stronger policies.

But I’m getting off track. The point is, implicit in the long quest for carbon targets is a desire to vault past the grubby, tedious work of changing interests and capabilities — to skip straight to the grand solution. That hope was always forlorn.

Carbon taxes

Carbon taxes are the economist’s version of Archimedes’ lever. Make it long enough — i.e., make the tax high enough — and you can move the world.

The key insight here is that you don’t just need a lever, you need a fulcrum; if the fulcrum is not strong enough to bear the weight, it doesn’t matter how long the lever is. In the case of a carbon tax, the fulcrum is the political will and power necessary to pass the tax into law with minimum loopholes and consistent enforcement. Offering a lever when no fulcrum’s in sight is not a solution.

Economists love carbon taxes because they maximize for efficiency in macroeconomic modeling. They disperse a price signal throughout the economy rather than “distorting” markets by concentrating on one sector or another. All else being equal, taxes will achieve carbon reductions with less impact on GDP growth than sector-specific mandates, rules, and subsidies. In the models. All else being equal.

But life is not a model and all else is never equal. No government or public in the world has proven willing to tax carbon as much as needed. After all, even if GDP growth remains robust, carbon taxes impose extremely visible costs on a lot of large, powerful constituencies. Macroeconomic models, unlike those constituencies, don’t get a vote and don’t donate money to politicians.

If there are limits to how much a public is willing to pay in carbon taxes — and there obviously are, though they will vary from country to country and circumstance to circumstance — then it is important to think about what kinds of policies either increase willingness to pay or reduce the cost of carbon reductions. “Does this policy reduce carbon?” is not the only question. We must also ask, “Does this policy create constituencies for further political action?” It is not only a policy’s effect on the economy that matters, but also its effect on political economy. (Jesse Jenkins wrote a great post about this, which you should read.)

What can make carbon taxes an easier lift? Cheaper renewables would do it, via mass deployment (feed-in tariffs, state renewables standards), early-stage market development, and basic research. More local and community ownership of renewables would help, too. At the metropolitan level, green manufacturing and service companies and the jobs they bring can make a difference. And so on.

These policies may look “inefficient” in a macro model, but guess what? A real policy, no matter how kludged and compromised, is always more efficacious than a theoretical policy. A carbon tax is the best (and only necessary) climate policy only on a blackboard or in a spreadsheet. In the real world, power and interests matter and anything that alters them in the right direction is desirable. Just as a carbon target means nothing until the policies and capabilities are in place, a carbon tax will only ever be as high as political economy allows.

The slow boring of hard boards

Just to make it very clear: I do not oppose carbon targets or carbon taxes. I would welcome either, at whatever level, with open arms.

But neither is a shortcut past politics. Neither is Archimedes’ lever. I think climate hawks should just accept and internalize the fact that progress on climate change will always be halting, incremental, incomplete, ugly, unpredictable, and hard-won. There is no climactic showdown, no “too late,” no “game over.” And there is no silver bullet solution. It’s going to be a long slog, through our lives and our children’s lives, pushing and pulling and scrabbling together a patchwork of policies. It won’t look anything like an economist’s model.

I personally think this is a healthier perspective than the boom and bust of too-high hopes followed by too-low despair that I’ve seen over and over this past decade. To fight for a sustainable path is not a discrete task, it’s a life, an orientation, an enduring context in which smaller, discrete tasks unfold. There is no “beating climate change” or “solving the problem.” There is no policy unicorn. There are only degrees of better or worse, opportunities claimed or lost, steps forward or backward.

I leave the final word to German sociologist Max Weber:

Politics is a strong and slow boring of hard boards. It requires passion as well as perspective. Certainly all historical experience confirms that man would not have achieved the possible unless time and again he had reached out for the impossible. But to do that, a man must be a leader, and more than a leader, he must be a hero as well, in a very sober sense of the word. And even those who are neither leaders nor heroes must arm themselves with that resolve of heart which can brave even the failing of all hopes. This is necessary right now, otherwise we shall fail to attain that which it is possible to achieve today. Only he who is certain not to destroy himself in the process should hear the call of politics; he must endure even though he finds the world too stupid or too petty for that which he would offer. In the face of that he must have the resolve to say ‘and yet,’ — for only then does he hear the ‘call’ of politics.