Brett VandenHeuvelThe Columbia River meets the sea near the site of the proposed terminal.

Last week, Beijing saw its infamous smog thicken to unprecedented levels, driven largely by emissions from coal-fired power plants across China. In recent years, coal from U.S. mines has stoked more and more of these plants, in effect off-shoring the health impacts of burning coal. This year, much of the U.S. coal industry’s focus will be on pushing an unfolding campaign that seeks to dramatically ramp up the amount of coal we ship overseas.

Morrow County, Ore., is a quintessentially green pocket of the Pacific Northwest. It’s capped by the Columbia River, which winds past the hipsters in Portland en route to the sea, often carrying schools of the salmon that have long been an economic staple for locals. But Morrow County could soon become a backdrop for the transformation of the U.S. coal industry, if a planned loading zone for massive shipments of coal — harvested in the Powder River Basin in Montana and Wyoming, and packed into Asia-bound cargo ships — gets final approval.

Right now, local, state, and federal lawmakers are hammering out the details in what is unfolding as one of the biggest climate fights of 2013.

Tim McDonnell

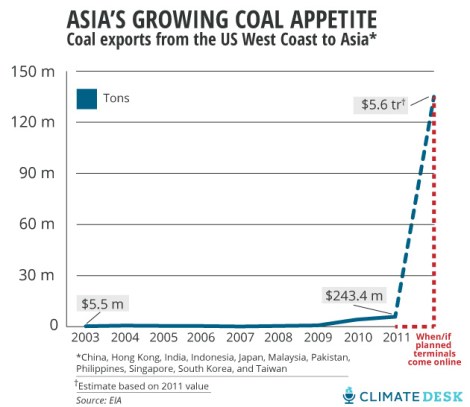

The Port of Morrow, where coal would be transferred from inland trains onto outbound river barges in the small town of Boardman, is just one of five proposed new coal-export terminals now under consideration in Oregon and Washington. If built, the terminals could more than double the amount of coal the U.S. ships overseas, most of it bound for insatiable markets in China, India, South Korea, and a suite of other Asian nations.

It’s the next giant leap forward for the U.S. coal industry, which has in recent years turned increasingly to the east as domestic demand dwindles and Obama-era clean air regulations make it next to impossible to build new coal-burning facilities at home. But Big Coal’s ability to sell its wares overseas is increasingly bottlenecked by maxed-out export facilities, most of which are on the Atlantic-facing East Coast, anyway, better situated for shipments to Hamburg than Hong Kong. So, says Brookings Institute energy analyst Charles Ebinger, building the new West Coast terminals could be a matter of life or death for U.S. coal.

“There’s a lot of coal in the domestic market that can’t be utilized,” Ebinger says. “The Asian market is the fastest-growing coal market in the world. If we wish to continue to export coal [these terminals] are very important … whatever volume of coal we could export would find a market.”

But as important as the terminals are to the coal industry, they’ve run up against a wall of resistance by everyone from local environmentalists to Oregon Sen. Ron Wyden (D), who has vowed to use his seat at the head of the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources to hold the terminal proposals to a rigorous environmental accounting.

“I’ve never seen such passionate opposition to a proposal as I’ve seen to coal export,” Brett VandenHeuvel, director of local environmental group Columbia Riverkeeper, says.

The opposition’s list of grievances, VandenHeuvel says, includes environmental degradation from increased mining, traffic disruption from massively expanded railroad activity, mercury poisoning in the Columbia, air and water pollution in the countries where the coal is ultimately burned, and global climate change from the release of so much carbon. The company pushing the Port of Morrow project, Australia-based Ambre Energy, has also come under fire recently for reports that it low-balled prices of coal mined from public land, thereby dodging federal royalty payments and ripping off taxpayers to the tune of several hundred million dollars (the company denies doing anything illegal).

A new Greenpeace study, released today, ranked the terminals as the fifth-dirtiest proposed energy project in the world, under Arctic oil drilling but above U.S. fracking and drilling in the Gulf of Mexico, finding that the increased coal use they would facilitate would, by 2020, dump some 460 million tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere every year. This echoes an EPA finding last year that the Port of Morrow terminal would pose “significant” local public health threats.

There are still a few hoops to jump through before any of the terminals could break ground, but with so much profit at stake, this is one climate battle that’s only getting started.

This story was produced by Mother Jones as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

This story was produced by Mother Jones as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.