One of the predicted effects of global warming is a shift in agricultural regions. Over centuries, certain areas have demonstrated suitability for certain crops — the right mix of rain and temperature and seasons. As the world warms, that balance shifts, meaning that areas good for agriculture suddenly aren’t, and regions that once weren’t good for production suddenly seem to be.

One of the predicted effects of global warming is a shift in agricultural regions. Over centuries, certain areas have demonstrated suitability for certain crops — the right mix of rain and temperature and seasons. As the world warms, that balance shifts, meaning that areas good for agriculture suddenly aren’t, and regions that once weren’t good for production suddenly seem to be.

In the Midwest, that migration is beginning to happen. From Bloomberg News:

While farmers nationwide planted the most corn this year since 1937, growers in Kansas sowed the fewest acres in three years, instead turning to less-thirsty crops such as wheat, sorghum and even triticale, a wheat-rye mix popular in Poland. Meanwhile, corn acreage in Manitoba, a Canadian province about 700 miles north of Kansas, has nearly doubled over the past decade due to weather changes and higher prices.

Shifts such as these reflect a view among food producers that this summer’s drought in the U.S. — the worst in half a century — isn’t a random disaster. It’s a glimpse of a future altered by climate change that will affect worldwide production.

The businesses that drive the agriculture industry aren’t wasting any time shifting infrastructure and resources.

Agribusiness giant Cargill Inc. is investing in northern U.S. facilities, anticipating increased grain production in that part of the country, said Greg Page, the chief executive officer of the Minneapolis-based company.

“The number of rail cars, the number of silos, the amount of loading capacity” all change, Page said in an interview in New York. “You can see capital go to where there is ability to produce more tons per acre.”

The drought has demonstrated that use of the already-withering Ogallala Aquifer is clearly not sustainable.

The harnessing of the Ogallala Aquifer, a massive underground lake that runs from South Dakota to west Texas [and] provides about 30 percent of U.S. irrigation groundwater, has allowed corn to flower where rainfall can’t support it. …

Ty Rumford, who manages High Choice Feeders LLC south of Scott City, Kansas, is planting less corn and more triticale to feed the 37,000 animals in his company’s two feed yards. A hardier crop is necessary as water availability falls, he said.

“When the wells were put down here in the ’40s, they went 30 foot down into a 180-foot-deep aquifer,” he said. “Those wells were pumping 1,500, 2,000 gallons a minute in the ’50s. Now we’re at 135 feet deep, and they’re pumping 200, 250 a minute. We’ve got to make sure we have enough water.”

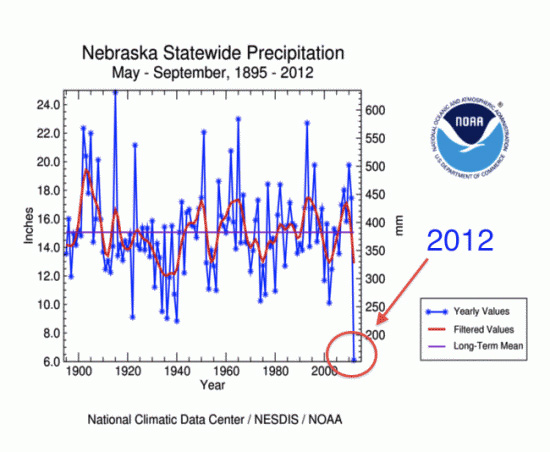

Yesterday, Climate Central noted just how little rain fell in Nebraska this year and included this graph:

That dryness is exceptional, to be certain, but farmers are betting that it will become less and less exceptional as the years progress. And when the stakes of the bet are one’s livelihood, there’s little choice but to change decades of tradition.