This story is part of a Guardian series on climate refugees. Read parts 1, 2, 3, and 4.

The slow-moving disaster being visited on the village of Newtok is a familiar one in Alaska. People are losing the ground beneath their feet, because of erosion.

Climate change has accelerated the normal process of erosion along Alaska’s rivers and coasts — especially near the shores of the Bering and Arctic seas.

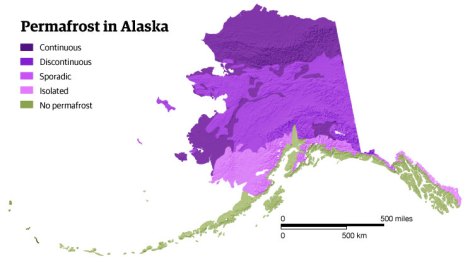

Warmer temperatures melt the permafrost, or frozen sub-surface layers which helped bind together the soil. Heavier rains produce more floods, and swollen rivers which wash away the soil. Waves break higher, because of sea-level rise, clawing at beaches.

Meanwhile, the sea ice that provided a barrier against intense storms has thinned and retreated, exposing coastal areas to tsunami-sized waves and 100 mph winds that are not uncommon in storms coming off the Bering Sea.

National Snow & Ice Data CenterClick to embiggen.

Alaskans have already begun exploring how to find the way back to solid ground. Some small communities may be able to reinforce coastlines by building broad, sloping rock walls known as revetments. But bringing heavy equipment, building materials and skilled labour to remote locations is prohibitively expensive — three or four times more than a comparable project anywhere else. The construction season is also short, further adding to the cost.

“Coastal erosion is a really, really expensive problem to deal with in an engineering mode,” said Orson Smith, an engineering professor at the University of Alaska at Anchorage. “It costs $10,000 to build one linear foot on a shoreline in a remote area, and you have thousands and thousands of feet of shoreline.”

Then there’s the matter of how the structures would stand up to the harsh Alaskan environment.

Shishmaref, a native Alaskan village located on a barrier island, has gone through an entire array of engineering projects — concrete blocks, wire mesh baskets, a broad sea wall made or gravel and rock. “A museum of erosion control,” Smith said.

Some of the early versions failed on deployment, and it’s not clear how the other structures will stand up over the years.

It’s also far from clear where Alaska will get the money for such ambitious engineering works, especially for small and remote communities.

Climate change is already adding billions to the bill every year just for maintaining existing infrastructure. A state government report estimated that erosion, flooding and other effects of climate change would add up to 20 percent to those costs over the next 20 years.

Then there is the issue of assigning priorities. About 90 percent of Alaska’s population lives within 20 kilometers of a coast, and the state’s most valuable resources — oil, fishing, minerals — are also in close proximity.

“There just isn’t enough money to go around to build a $50 or $100 million revetment for a village of a few hundred people that has other problems,” Smith said. “The money that is spent on those kinds of structures to save a village could be applied to move the families to somewhere else.”

There are other remedies for villages that want to protect against erosion. Communities are now looking at how to plan for a slow retreat to higher ground, gradually replacing old buildings by new raised structures, or moving buildings to higher elevations. But many communities have no higher ground or room to retreat.

Others, like Newtok, are situated on low-lying, wetlands that simply can not support the large engineering projects that would be needed to make them safe. They have no choice but to move.

This feature originally appeared on the Guardian website as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

This feature originally appeared on the Guardian website as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.