In January 2013, Maseno School in western Kenya had just completed a brand new dormitory, but the building’s shoddy sanitation system was a stinky mess. Founded in 1906 by Christian missionaries, Maseno is the oldest English-language school in Kenya and counts President Obama’s pops among its notable alumni. The new dorm, home to 720 students, featured a pit latrine and malfunctioning sewer system that, predictably, smelled like shit. Periodic blockages brought on by lack of water made the foul odors even more putrid, and the faulty sewer system contaminated a nearby stream that provided freshwater to the community.

Meanwhile, using firewood for cooking fuel was causing more problems. Burning wood in the school’s kitchen poses a serious health risk, threatening the lungs and throats of those who prepare food. And cutting down trees for firewood fuel provokes conflicts between the school and the surrounding community as the forest is depleted. Polluting the local water supply aggravated these rifts, to the point that locals protested the completion of the dormitory.

Leroy Mwasaru and four fellow students had an idea to address the issues caused by inferior sewage systems and wood-fired cooking at once. Mwasaru, now 17, in his last year of high school, explains: “Through a group of five, I initiated the idea that … if we harvested this waste from the 720 students and also used the organic waste that comes from the kitchen, slashing grass, and cow dung, we can come up with a viable solution.”

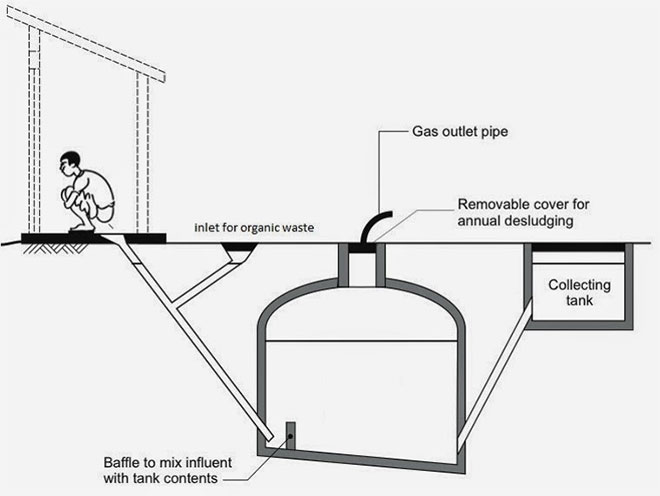

Enter Mwasaru’s proposal for a human waste bioreactor, or HWB, which produces biogas for cooking from these so-called wastes. An underground chamber holds the human, animal, and kitchen excrement, while microorganisms go to work breaking down the muck. This process releases biogas, a source of renewable energy comprised mostly of methane, the same as the fossil fuel natural gas that powers most non-electric stoves in the U.S. The gas is contained in the HWB, ready for use as fuel.

This poo- and refuse-derived cooking fuel replaces firewood in the kitchen, improving the health of cooks, forest ecosystems, and community relations. Burning biogas is good for climate health too: It offsets the need for fossil fuels and prevents the methane produced by organic stuff decomposing from escaping into the atmosphere to trap heat.

Here’s what the original plans looked like:

Mwasaru has relentlessly pushed to bring the HWB to life. Soon after the new dorm had opened, he and his biogas buds entered the inaugural Innovate Kenya challenge, put on by Global Minimum, a nonprofit organization that helps teenagers in Kenya, South Africa, and Sierra Leone develop creative projects to address social problems in their communities. Their HWB project was selected as a winner, which meant Mwasaru and company got to attend the first Innovate Kenya camp this past June. There, they designed a prototype with help from MIT students and lecturers.

At a second Innovate Kenya camp, in September, the Maseno team presented the working prototype and successfully raised enough money to purchase a plastic digester — the big container that holds wastes as they’re breaking down to produce biogas — for their next demonstration. The gadget enables the group’s second prototype to pump biogas directly into the school’s kitchen.

Today, HWB No. 2 is up and running. Mwasaru says they feed this prototype organic waste from the school farm as well as food remains from the staff and students. The kitchen cooks with the biogas, though not exclusively, since the plastic digester produces only small volumes.

Earlier this month, Mwasaru got to present at the Techonomy 2014 conference in Half Moon Bay, Calif., participating in a panel discussion on how his generation is rethinking innovation in Africa (check out the video). Innovate Kenya chose him from 32 finalists to make the trip. It was his first time on an airplane.

Mwasaru relished the opportunity to share his idea while also learning from the creations and experiences of other conference-goers. He networked with Microsoft engineers and moguls like LinkedIn founder Jeff Weiner, finding new confidence and inspiration with each encounter.

Relentlessly focused on improving the HWB, Techonomy even provided Mwasaru a new techie idea to bring back to Kenya: biohacking, which means combining biological science with the hacker ethic of using free information to improve processes. For his project, this means introducing various organisms into the bioreactor to speed up the production of biogas.

The HWB team. Innovate Kenya

As for the future of the HWB, the team has big plans. “After the success of our second prototype, we have been hands on, working on designing a human waste bioreactor toilet that separates urine from [the] solid part, stool, since urine will lower the rate of gas production or, worse still, stall the whole process,” says Mwasaru.

The real HWB project, which will serve the school’s approximately 1,200 students, will cost around 7 million Kenyan Shillings, or $85,000, according to Mwasaru. Raising the funds won’t be easy, he admits, but the group calculates that cooking with the biogas will save the school more than half that much money in firewood expenses.

But Mwasaru and his team’s plans don’t stop there; they want to form an HWB company to realize the bigger potential of the technology. Mwasaru says he imagines charging customers according to their ability to pay, with wealthier folks in essence subsidizing the projects that would provide access to sanitation, clean cooking fuel, and even electricity to rural and low-income communities who couldn’t otherwise afford it — or maybe aren’t on the grid.

Creating change in the way a community thinks makes all the difference, in Mwasaru’s view, and holds the key to addressing fast-depleting resources and the effects of climate change. Through the HWB venture, he wants to show people how they will benefit from new, clean energy by simply shifting their perspective on what’s considered “waste.”

Angel investors, get in touch.