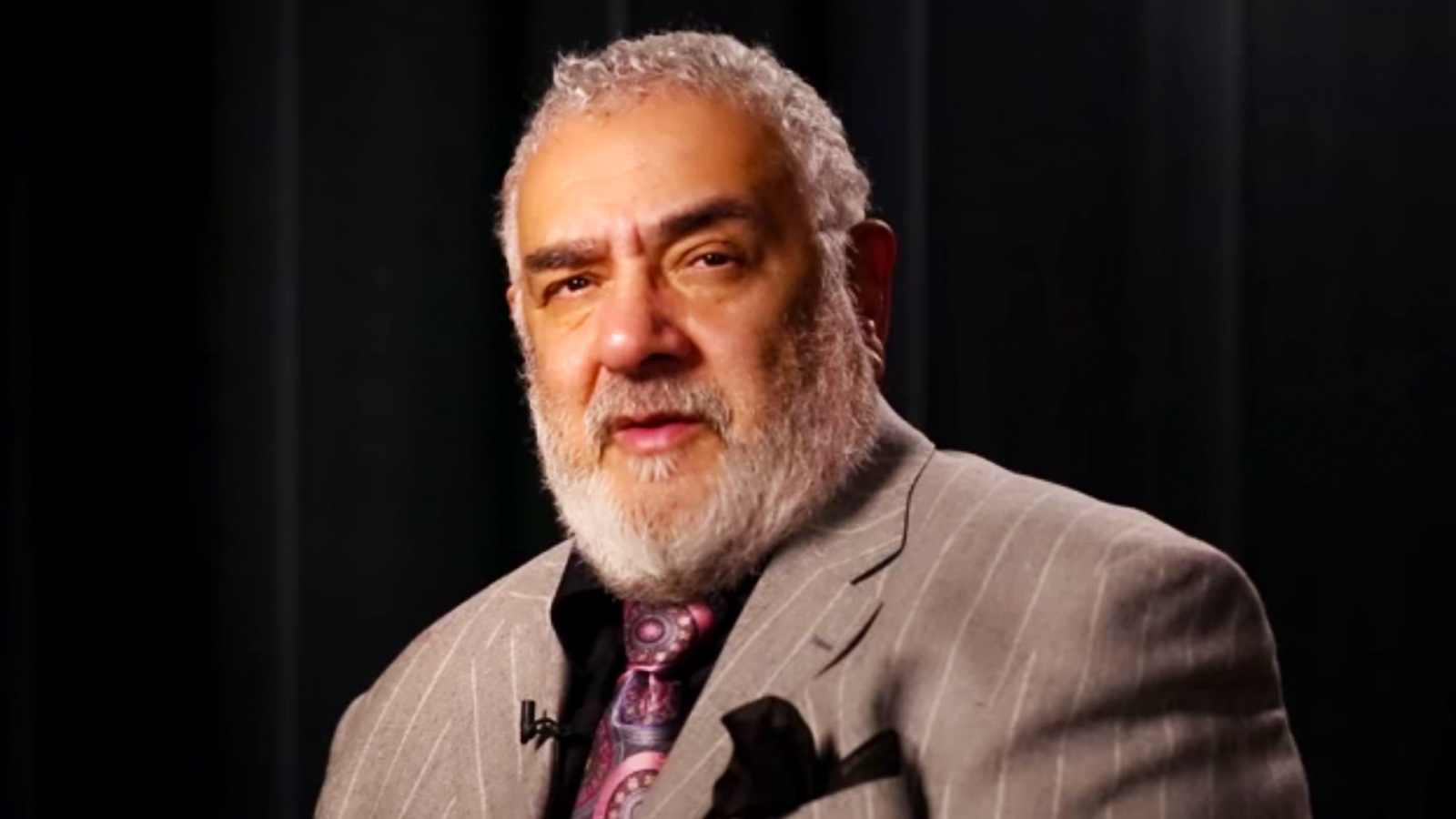

So, I’m sitting in the cafe in Politics & Prose preparing to blog on this video that the Environmental Protection Agency just posted on its YouTube page when I hit a snag. I want to quote one of the talking heads featured in the video, an attorney for the Department of Justice who’s identified as “Quintin Pair.” But I need to make sure I have his name right, because Journalism 101.

I’ve seen this guy before, at the EPA’s ceremony honoring civil rights veteran Rep. John Lewis earlier this year, and knew intuitively that he was a major if silent figure in the environmental justice movement. But I don’t know anything else about him. So I Google him. Nothing comes up for “Quintin Pair.”

Do you mean Quentin Pair? Google asks. A few results come up when I clicked on that spelling, but I’m still not sure.

I’m thinking, surely EPA knows its own people’s names better than Google. And then I look up from my table, and I kid you not, a man walks past me who looks exactly like the guy in the video. At first I write it off to hallucination due to over-caffeination. But then he walks by me again, and then a third time, still looking every bit the part. Finally I stop him.

My first question: You wouldn’t happen to be Quentin Pair?

It is him. I tell him that I just happened to be watching an EPA video that features him, which I use as leverage for my second question: Do you mind if I interview you real quick? He smiles and tells me that he needs to take these books he just bought to his car first, which I instantly interpret as He’s going to get in his car with his books and drive off, because I know serendipity ain’t always that sweet. But he comes back! He sits at my table and goes, “So what do you wanna know?”

My response: Um, how do you spell your name?

The interview is not real quick. We talk for hours, closing the coffeeshop. Besides working as an attorney for DOJ’s Environment and Natural Resources Division, with EPA as his “client,” he also teaches at Howard University’s School of Law and co-directs its environmental justice seminar. He’s been a behind-the-scenes mover on federal EJ policy since it became a thing and has helped develop it since.

As much as I’d like to, I can’t share everything that he shared with me — at least not yet. But here are five things he told me during our talk:

1. How the Justice Department got involved with EPA’s new environmental justice program:

I was roped in by Clarice Gaylord, who is my mentor. That’s how I discovered environmental justice. I was minding my own business over at DOJ and I saw that EPA was looking for attorneys to serve as counsel for their Office of Environmental Justice. I didn’t know what that was, but I wanted a break from suing people — Love Canal was one of my cases. So I went over and talked with [Gaylord] and we hit it off instantly.

One of my first meetings with EPA was about a dam project in Virginia. Representatives from the Army Corps of Engineers were there and they had been working on it for some 10 or 15 years. But [EPA] Region 3 director said he wasn’t going to sign off on it, because it wouldn’t comply with 12898 [President Clinton’s executive order requiring every federal agency to consider impacts on minorities and low income before implementing policy rules]. He said that the people who would be affected by this dam needed to have input and participate in the decisionmaking. Then he points to me and says, “Quentin Pair the attorney is here and he’ll explain it.” I had just read the executive order the day before.

2. About that dam project:

There is an Indian tribe in Virginia, not federally recognized, the Mattaponi, and they had some territory up and down the East Coast. This dam was going to run through their towns and the Army Corps neglected to bring the tribes into the conversation.

The [Mattaponi] had a treaty from the 17th century that gave them a three-mile no-man’s-land buffer around their reservation. But this dam would’ve run across that cutting them off from the [Mattaponi] river, which would have impacted their fishing industry and livelihood.

I got a call from someone in the Army Corps of Engineers and he’s shouting and fussing at me: “What are you people doing? You have no jurisdiction!” and all the rest. They were mad because EPA was sticking its nose in their business. I explained to him Executive Order 12898, and he had no idea what I was talking about.

They called a big meeting with us, with all the Corps people sitting at one side of the table and us and EPA on the other. All of a sudden a One Star General walks in, walks right past his people and sat next to me at the table. He said, “I just read the executive order, and I don’t believe this project will comply, so I’m not going to approve it. He was their district commander. [For more on this read this and this.]

3. How young people saved both civil rights and environmental justice:

In the 1980s, in Warren County, N.C., where you have a bunch of minorities and poor people living, and where few have access to their representatives in the legislature, the state decides it’s going to put this landfill, and fill it with all kinds of PCBs and cancerous waste. There’s no public notice about this, nothing in the local newspapers, and then the state doesn’t line the landfill with anything.

On the opening day of the landfill, some 500 residents came out and laid down in the road where the trucks were supposed to carry the trash to the site. It attracted media attention not only because it marked the rise of the EJ movement but also because all 500 of them were arrested. What interested me the most is that many of them were children. So there were shades of Selma.

Now most people don’t know that the Civil Rights Movement was almost destroyed at one point. Everything from the Freedom Summer activities and all those demonstrations throughout the 1950s and 1960s had all these people getting arrested and jailed. Civil rights groups like the NAACP had run out of money from bailing them out and all these lawsuits. But when Bloody Sunday happened in Selma and the national news picked up how they were arresting and beating children, that’s what saved the civil rights movement.

Fast forward to 1982 [and the Warren County demonstration]: here come the children again. [Editor’s note: The youth are still getting it done.]

4. What environmental justice meant then:

One of the people arrested was Rev. Walter Fauntroy, one of most prominent black ministers in D.C. and a founder of the Congressional Black Caucus. As D.C.’s delegate to Congress, he sent a letter to the Government Accountability Office saying, “I want you to do a study on the siting of hazardous waste facilities in the Southeast and do a demographic analysis.”

They found that three out of four waste facilities were sited in African American communities or poor communities, and that the single most determining factor in the results was race, while income was second. A few years later, in 1987 Charles Lee was hired by the United Church of Christ to research this thing nationally. Ben Chavis was hired as his assistant along with Vernice Miller-Travis. That was the Toxic Waste and Race report and they found that still 3 out of four waste facilities were in poor or minority neighborhoods, and again, the single determinative factor was race.

So twenty years later, in 2007, Dr. Bob Bullard teams up with Dr. Beverly Wright and Paul Mohai from the University of Michigan, and they’re saying, “OK, we have some more data and better [research] tools now, so let’s go back to the Charles Lee report and do some new studies to see if it still holds up.’ The results were even worse.

5. What environmental justice means today:

One of the main tenets of EJ is that affected communities need to have their voices heard and in a meaningful manner. Well, those are nice words, but how do you make that happen? Under [former EPA Chief] Lisa Jackson and her associate administrator Lisa Garcia’s leadership, they created a Memo of Understanding in 2011, which 17 federal agencies came together and signed, saying not only would they support Executive Order 12898, but they would expand on its work by submitting strategies on how to implement it and give annual reports.

Each agency has an EJ coordinator, and there’s an EJ directory that lists all of them and how to contact them. If anyone in the public has a concern or issue they can use that directory to call one of us. I might not be able to solve your concern, but I can get you to the right person in the right agency and find out where you should go to get the problem addressed.