For 60 years, BP has been gathering data for its widely respected Statistical Review of World Energy, a yearly compendium of info on global energy use. In 2011, for the first time, it published a forward-looking analysis to go with: the BP Energy Outlook 2030.

The Outlook combines long-term energy trends with educated guesses about the course of economic growth, policy, and technology, resulting in BP’s “judgment of the likely path of global energy markets to 2030.” The document can thus be read as a distillation of what today’s elites expect in the next 20 years. And what they expect is profoundly disturbing.

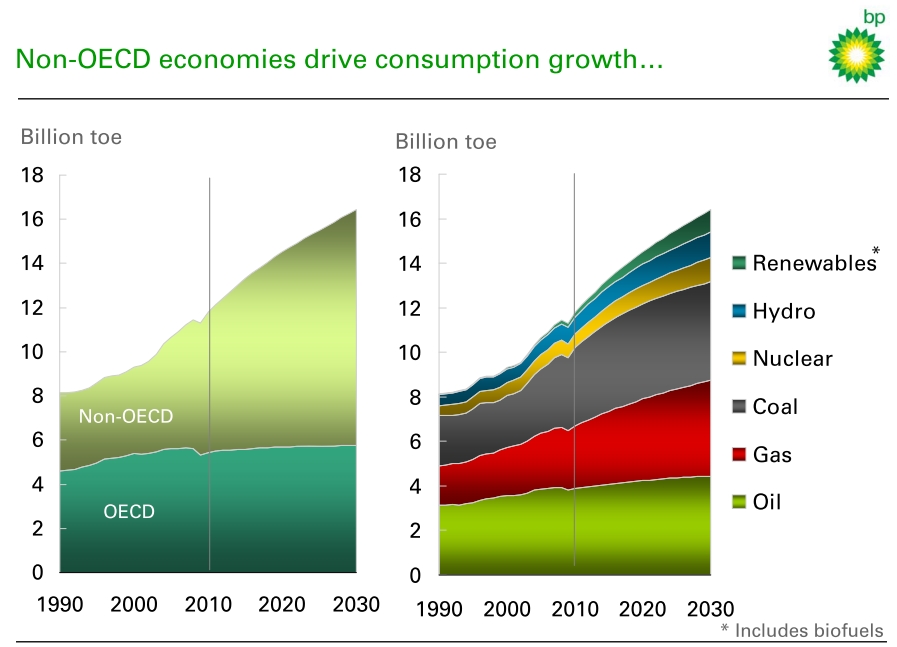

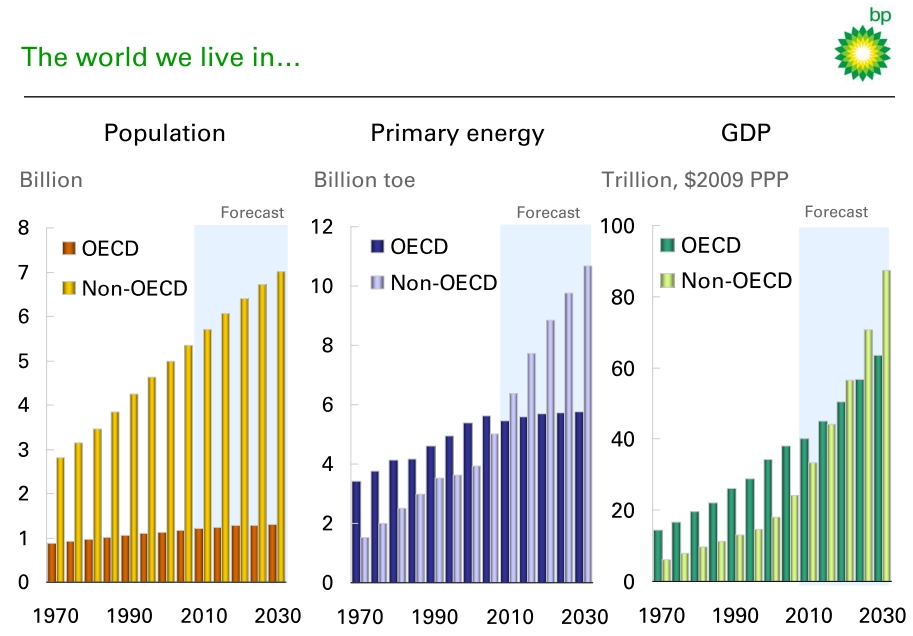

The basic story is: growth, but not evenly distributed growth. Developed countries are expected to plateau in population and energy demand, but developing countries are expected to grow like gangbusters:

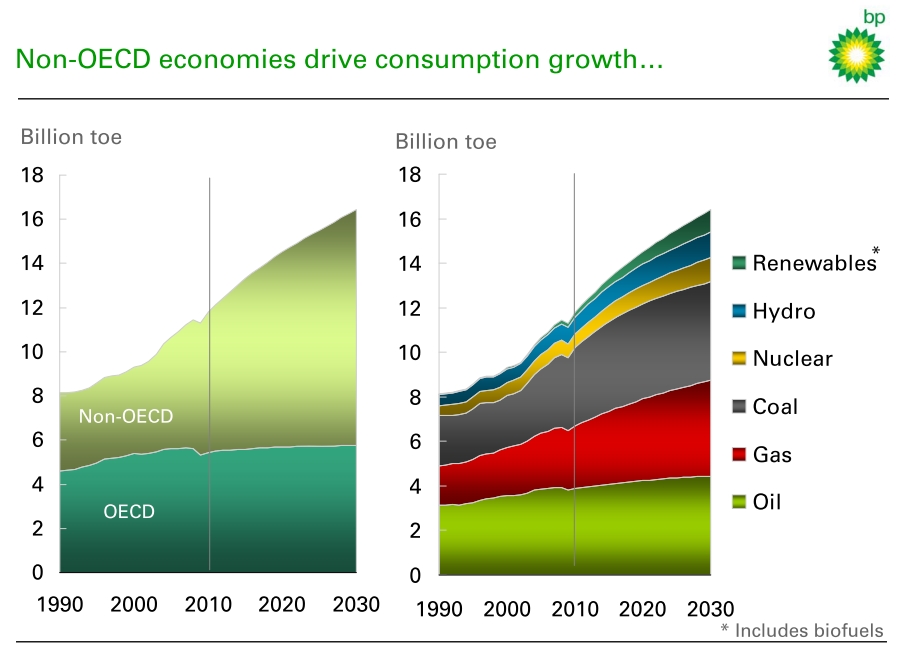

What kind of energy will satisfy all that new demand? While renewables and natural gas are expected to grow faster than ever before, and oil and coal are expected to substantially slow their growth, there will nonetheless be more oil and coal burned in 2030 than in 2011:

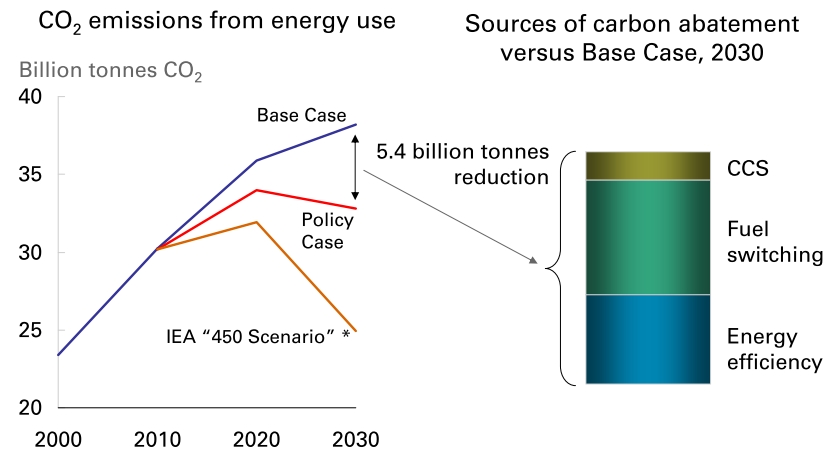

Predictably, this growth in fossil fuel consumption will drive growth in greenhouse gas emissions:

See that “Policy Case” in the graph above? That’s what BP sees happening if policymakers get religion on climate change and “a wide range of policy tools are deployed, including putting a price on carbon.” You’ll notice that the Policy Case — BP’s optimistic case — doesn’t even get halfway to what’s necessary to hit 450 parts per million of CO2 in the atmosphere, the official UNFCCC target. Hitting that target would require a policy regime over twice as ambitious as the most ambitious thing BP can realistically see happening. And the latest science strongly indicates that 350 ppm, not 450 ppm, is the safe leve. BP’s people don’t even bother putting that on the chart, it’s so outside the realm of possibility.

This, then, is humanity’s core dilemma: According to the best judgment of our intellectual elites, our current path leads to catastrophe. Yet those elites cannot even envision a scenario in which that catastrophe is avoided. We’re headed for suffering and we have no idea how to avoid it.

You’d think that would raise some alarms among U.S. policymakers. Perhaps even as much alarm as, say, fake deficit concerns. But it’s not. There is quiescence. Quiet. It’s just bizarre.

So what could change our course? I can think of three things:

1. Greater than expected resource constraints, i.e., a big dropoff in oil and coal production. There are, as I’m sure you’re aware, lots of peak-this and peak-that folks out there who say that this is all but inevitable, and that the “official” production numbers of the aforementioned elites are little more than hopeful fantasies. Sharp resource constraints would, perhaps, avoid the worst of climate change, but they would do so mainly by slowing the economy, so it’s not exactly something for which one wants to cheer.

2. A truly radical global shift in policy, perhaps if someone slips MDMA into the water supply in Durban. For example, the Outlook assumes that transportation will continue to be the big driver for oil demand, especially in developing countries, and that “rail, electric vehicles and plug-in hybrids, and the use of compressed natural gas in transport is likely to grow, but without making a material contribution to total transport before 2030.” Presumably, if policymakers wanted, they could devise ways of driving transportation alternatives to market much faster and at much larger scale. Another example: BP expects renewables to have a 10 percent share of the global power market by 2030. There are plans on paper to push that number much higher, if policymakers wanted to use them.

3. Technological breakthroughs, woo! Always the big X-factor in projections like this; it’s impossible to know how fast technology will advance. Of course, we could do things to make it advance faster … but that would require some of that smart policy that seems in such short supply.

Getting close to a safe and prosperous outcome will probably require some of all three. We are cursed, it seems, to live in interesting times.