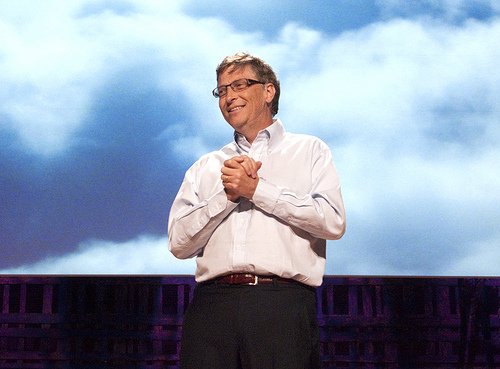

So right, and yet so not-quite-rightPhoto: Suzie KatzWhen Bill Gates first jumped into the energy discussion with a big TED talk, I wrote a post called “Why Bill Gates is wrong.” In retrospect, I should have been a bit more diplomatic. I should have started with a post called “Why it’s super-fantastic that someone as smart, influential, and wealthy as Bill Gates is taking climate change seriously and pushing policymakers to do something about it (but P.S. he’s wrong about a few things).”

So right, and yet so not-quite-rightPhoto: Suzie KatzWhen Bill Gates first jumped into the energy discussion with a big TED talk, I wrote a post called “Why Bill Gates is wrong.” In retrospect, I should have been a bit more diplomatic. I should have started with a post called “Why it’s super-fantastic that someone as smart, influential, and wealthy as Bill Gates is taking climate change seriously and pushing policymakers to do something about it (but P.S. he’s wrong about a few things).”

So let me start this post by saying that it is genuinely great that Gates has identified this problem and is thinking big — really big, like “we need to get to zero carbon” big — about solutions. That is an unqualified win for the underpowered movement against climate change. And in his comments at a Seattle event on Tuesday, he seemed to be a little less dismissive about energy efficiency and existing technologies than he has been in the past. He just wants the focus to shift more to basic R&D and innovation, ’cause of all the “miracles” we need to get to zero carbon.

It still seems to me, though, that he’s got a couple of blind spots — and oddly, the blind spots are lessons that you’d think Gates, of all people in the world, would have learned, since they are key to his success with Microsoft.

First, deployment can change the world. Rather famously, Bill Gates and his early Microsoft crew didn’t invent anything new or groundbreaking. Personal computers already existed (remember Tandy?) and the graphic interface idea (“windows”) was already featured in Apple products. What Microsoft did is scale those ideas up — way up — through deployment. They made productivity software cheap, easy (enough), and ubiquitous, learning as they went along how to incrementally improve it. They never had the best products, the ideally researched and designed products, they just had relentless business discipline. The folks at Apple spent more time in the lab, spit-shining and perfecting things, but Microsoft learned by doing. And it’s Microsoft, not Apple, that’s most responsible for the fact that everybody and their cousin now owns and knows how to use a computer. (Dell did something analogous with the PC itself. They didn’t invent anything, they just made computers easy (enough), cheap, and ubiquitous.)

But for some reason, when it comes to energy, Gates has no faith in deployment. He thinks we spend too much money encouraging deployment of existing energy tech. Why? Why couldn’t deployment do for energy what it did for computing? He was asked that question yesterday and, in my opinion, offered a weak answer.

He said energy investments are bigger, and the life cycles are longer (40 years or more), so deployment won’t produce the same kind of rapid learning curve.

Now, that’s true of the gigantic power plants he’s so enamored of. But then, if we’re so focused on innovation, why don’t we turn the policy focus away from gigantic power plants and toward the kinds of technologies that have shorter lifecycles, smaller investment increments, and steeper learning curves?

Which brings me to the second blind spot: distribution accelerates innovation. If anyone should understand this, it should be the guy who masterminded the personal computing revolution. Computers used to be gigantic, centralized mainframes run by small groups of super-geeks in big IBM labs. Those early computer guys were completely dismissive toward the very idea of personal computing. After all, you’d end up with small, underpowered machines operated by lay people who didn’t even have PhDs in computer science. What could come of that?

Of course, once computing power was decentralized, widely dispersed into the hands of ordinary people, the world saw an explosion of innovation and economic productivity the likes of which hadn’t been seen since the post-WWII boom.

The same could be true of energy. There’s a whole suite of “distributed energy” technologies — including the “cute” rooftop solar panels Gates dismisses along with other small-scale generation, energy storage, and various IT-based smart-grid widgets — that can put the power to create and manage energy into ordinary people’s hands. Especially given America’s plateauing energy demand, we’re just not going to need that many more huge power plants. The small, smart, distributed stuff is the very stuff that will enjoy rapid iteration and innovation cycles. It’s the very stuff that could change the world through deployment.

Why Bill Gates, who witnessed the computer revolution — distribution plus deployment — doesn’t apply the same lessons to energy is something of a mystery to me. This is an area where he could be a real thought leader. He could help mastermind a second empowerment revolution. Wouldn’t that be neat?