Remodeling an old pad like these ones, in Baltimore, is more eco-friendly than building a new one. (Photo by cinderellasg.)

Looking for the ultimate earth-friendly bungalow? No need to engineer some LEED certified space pod. Buy an old house and gird yourself for an eco-friendly remodel.

A study released Tuesday finds that in almost every instance, remodeling an old building is greener than building a new one. Beyond that, it shows that reusing old buildings provides immediate results in the fight against climate change, while a relatively energy efficient new building won’t pay climate dividends for decades.

Taken to the scale of the city, the study has some fascinating implications. Cities, it turns out, serve as a sort of carbon sink — the existing buildings hold a tremendous amount of “embodied energy.” Conserving that energy by sparing these buildings from the wrecking ball does a lot of good for the planet, too.

The study, called “The Greenest Building: Quantifying the Environmental Value of Building Reuse,” was done by the Seattle-based sustainability think tank Preservation Green Lab, an offshoot of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. It stands to reason that a group that fights to save old buildings is going to argue that its particular fetish is the grooviest, but The Greenest Building is a painstakingly detailed piece of work.

The researchers looked at seven different building types in four different cities, using “life cycle analysis” to compare everything from the impacts of producing building materials to the implications for human health and the costs of disposing of a structure at the end of its life. In calculating the climate impacts, they went so far as to compare the source of electricity in different cities. (Chicago gets almost two-thirds of its electricity from coal, while Portland gets almost a quarter from hydroelectric dams, for example.)

In addition to concluding that reusing old buildings is almost always greener, the study finds that it can take decades for a new, energy-efficient building to make up for all the energy that goes into building it. When it comes to climate impacts, new buildings can take 10 to 80 years to catch up to old buildings that have had energy-saving retrofits.

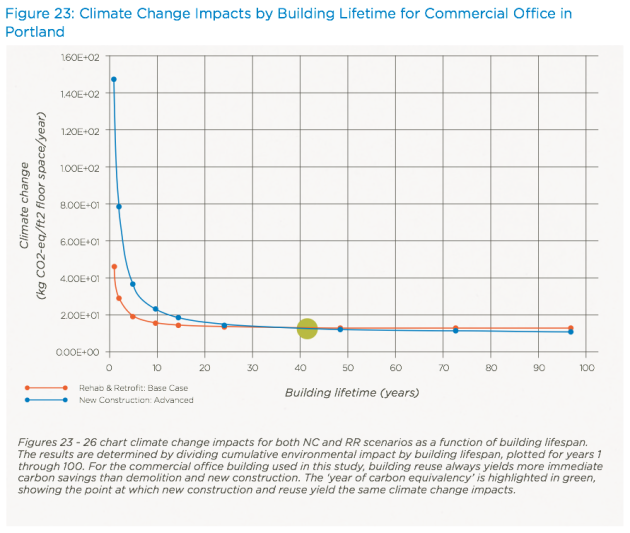

Here’s a handy chart to help you picture this:

The blue line tracks the climate impacts of a new building (an office building in Portland in this case, though the details aren’t super important), while the red line shows the impacts of a rehabbed older building. The green dot, at year 42, shows the point of “carbon equivalency,” when the new building finally makes up for all the energy that went into it and catches the old one.

To get your head around the broader implications here, consider this: The Brookings Institution projects that the U.S. will demolish roughly a quarter of its existing building stock — 82 billion square feet — between 2005 and 2030, and replace it with new structures. That’s a mind boggling amount of new construction, and even if the new stuff is significantly more energy efficient than the existing stock, it will take decades to recover the initial environmental costs of building it all.

We don’t have that kind of time. (Need a refresher? Here’s Grist’s David Roberts on the brutal logic of climate change.)

What if we reuse those buildings instead of bulldozing them? In Portland, Ore., alone, the study estimates that if the city were to retrofit the single-family homes and office buildings that it is otherwise likely to demolish over the next decade, it could save roughly 231,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide. That’s about 15 percent of the county’s CO2 reduction target for the next decade.

And that’s Portland, folks. Apply that to a city like Baltimore, where Chris and Snoop famously dumped bodies in the “vacants” in The Wire. There are 16,000 vacant homes in Baltimore. Many of them are crumbling. Some are beyond repair. But the rest are green retrofits waiting to happen, and you’ll find similar situations in aging cities across the country.

If we could save those homes, fix them up, and put people back in them, we would not only do the city a world of good, we’d be doing the world a city of good by sparing it the impacts of a boatload of new building.

OK, I know. I’m sounding a little starry-eyed here. We’ve been trying to revive our aging industrial cities for ever, with limited success. (I wrote about one of Baltimore’s struggling neighborhoods in a story a few years ago, here.) And old houses present myriad challenges ranging from leaky roofs to lead paint. (In Baltimore, many homes are in such bad shape that they didn’t even qualify for stimulus-funded energy-saving retrofits — and those are the homes that people are still living in!)

Nonetheless, Americans say they are ready to move back to the city. With the right incentives, they might be convinced to make the leap. The Greenest Building offers more fuel to the argument that we’d be wise to give them whatever nudge is necessary.

Find more information about The Greenest Building or download a pdf of the report here.