Third in a series on California water issues.

Janette Oregon has lived in the Los Angeles area since her parents moved from Mexico when she was a little over a month old. But she’s never swallowed a drop of municipal tap water. Neither have any of her friends or neighbors.

“I don’t even think I know anybody,” says Oregon, who is 28. “My kids, maybe, with the hose when they’re getting wet.”

Driving through Whittier, California, Oregon points out her childhood home near a 7-Eleven and her middle school a few blocks away. She says the city — which sits on the outer edge of L.A. County and has a population of nearly 90,000 — has changed considerably during her lifetime, seeing an influx of people and businesses. But Wateria, a filtered-water store, has occupied the same storefront in the city for 20 years. It was Oregon’s first place of employment, and she still works for the company today.

“Buenos dias, Paz,” Oregon calls to the one employee working at the store the morning we visit. Paz Herrera would usually be busy filling water bottles for customers, but on this day, the weather is gloomy, chilly, and rainy — a rarity — so business is slow. “Any other day, the line would be out the door,” Oregon says.

The service table at Wateria’s flagship store in Whittier, California. (Emma Foehringer Merchant)

Un Kim, a Korean immigrant, opened this store in 1996. Since then, Wateria has grown into a regional chain of 21 stores, most of them in L.A. County. Kim and other Korean entrepreneurs own 20 of them.

Anywhere in L.A., water stores do brisk business. Customers, many of them Latino immigrants or second generation, bring three, five, even 30 jugs to be filled at outposts such as House of Living Water, Oasis Water Store, and Wonder Alkaline Water. Vending machines where people can fill up bottles with water also occupy corners throughout the city. But Kim, with his franchises and sleek storefronts, is a full-blown water mogul.

Wateria’s popularity demonstrates the unique culture immigrants have forged in Los Angeles, and the distrust many of them have for public services. Customers pay a premium of hundreds of dollars a year to drink filtered water instead of tap water because they’re more confident in its safety or think it tastes better. Communities of color and low-income areas in the United States are more likely to have contaminated drinking water supplies, and trust in public water systems has been further battered by the lead poisoning crisis in Flint, Michigan.

But water experts and municipal water providers contend that most tap water is safe. They point out that some filtered and bottled water is even more contaminated than what comes out of the tap. Still, demand for the filtered stuff is persistent enough to keep Wateria doing good business.

Inside the Whittier store, red and yellow slushies swirl in plastic machines. An ice cream freezer hums near the front window. Cold drinks, including soda and Wateria-branded water bottles, sit in refrigerated cases near the entrance.

“The slush here, even though it has sugar, is made from our water,” says Oregon, nodding at the spinning ice crystals. “Our coffee also uses our water — it’s just automatic.” Bags of ice are made with the company’s filtered water, too.

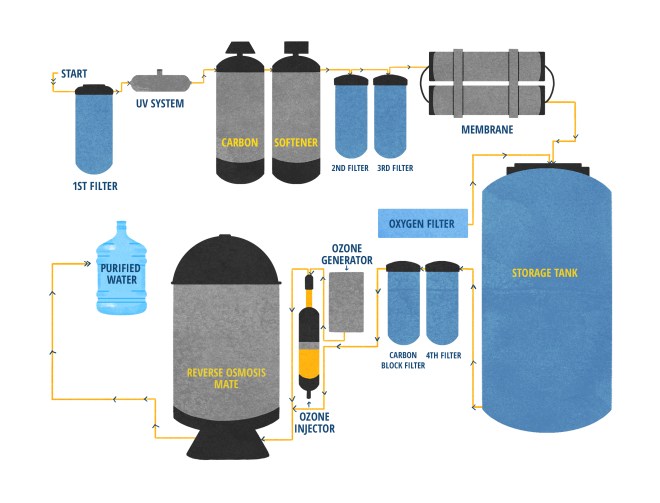

Further inside, the store’s crown jewel sits behind a plate of glass: a gleaming reverse osmosis machine. The tangle of wires, meters, and silver cylinders makes up Wateria’s “13-step drinking water purification system.” Kim, an engineer who used to work on portable televisions, designed the system based on a technology first developed by a French physicist in the 1700s and later refined by researchers at Dartmouth.

Displaying the machine is a signature Wateria move; the owners say it builds trust in their product. That helps the average Wateria store sell about 30,000 gallons a month. The Whittier store, the chain’s busiest, sells about 75,000 gallons a month.

The day I visit, the machine is pumping out 3.2 gallons of filtered water per minute. The process starts with municipal tap water. It runs through a series of filters, a UV purifier, a salt softener, as well as a few other steps before it gets pumped up to the service table, where attendants dispense it into five-gallon plastic jugs or whatever containers customers bring in.

Wateria’s 13-step water purification system. (Grist / Amelia Bates)

Oregon worked at this store filling those containers for two and a half years. Now, she works in accounting and payroll at Wateria headquarters in a nondescript Whittier office park surrounded by birds-of-paradise and a residential neighborhood.

She’s been with the company for a decade. Sticking around that long is not unusual. Herrera has worked at Wateria for 16 years. Leslie Jimenez, another decade-long employee who works at stores in the L.A. suburbs of Norwalk and Downey, told me Wateria feels “kind of like a second family.”

It’s a family business in a more literal sense as well. Un Kim’s daughter, Kelly Choi, is Wateria’s CFO. I meet the two of them in an upstairs conference room at the company’s headquarters. It’s decorated with nautical kitsch: a wooden figurine of a captain at a ship’s helm, framed sailing knots, and several model sailboats, including one branded with Wateria’s logo. Kim says the trinkets remind him of the small, sparsely populated island where he grew up in South Korea. “I have very strong nostalgia, still,” he says with a smile.

After arriving in Southern California in 1994 with his wife and children in tow, Kim noticed that many residents bought water at vending machines in their neighborhoods or had it delivered. He saw an opportunity and, with his engineering mind and entrepreneurial spirit, seized it. He built his first reverse osmosis machine by hand, and still pieces together the machines himself in Wateria’s warehouse before each new store opens.

According to Choi, the vended water market really blew up in L.A. in the early 2000s. “Every block, there was a water store,” she says. But Wateria struggled at first. Kim keeps the small spiral notebooks in which he used to meticulously track the day’s sales in neat rows. On Wateria’s first day, he made just $13.

“This is my history book,” Kim says, pushing it toward me. “People told me, ‘You are crazy. You are going to be closed soon.’” But 20 years later, Wateria is thriving.

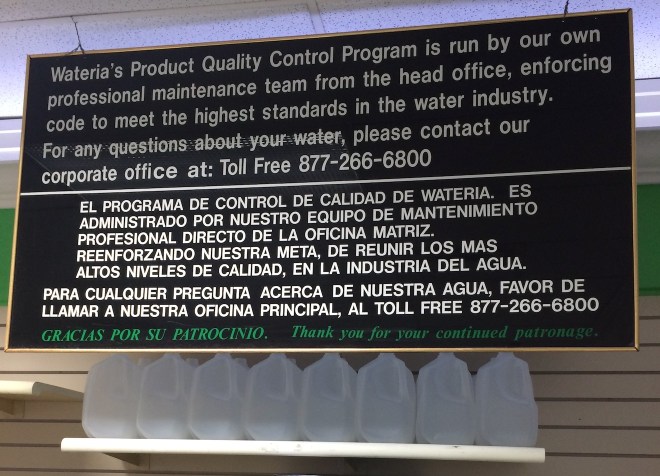

Choi says the company stays ahead of the abundant filtered-water competition because its water is high quality. Wateria, as she portrays it, is the BMW of water stores. That’s a hard claim to test, but the company is in good standing with the state Department of Public Health, which regulates water vendors. Independent tests submitted to the department show that Wateria’s levels of total dissolved solids are consistently below allowable maximums set by the Federal Drug Administration for “purified” water, and its levels of coliform bacteria and other potential contaminants also meet standards.

A sign displayed in a Wateria store. (Emma Foehringer Merchant)

“The people who drink our water actually drink a better water than the Sparkletts and Arrowhead,” Choi says, referencing other commonly consumed brands.

Oregon, too, believes Wateria offers a better product. “There are always the mom-and-pop shops,” she says. “Usually once they come here, they don’t go back.”

Not everybody is lining up to fill bottles, though. Jeff O’Keefe, the Los Angeles region chief for the California State Water Resources Control Board’s Division of Drinking Water, seems perplexed that so many people rely on water stores.

“I know that many immigrants have come from countries where they don’t have confidence in their home country’s drinking water supply, so they often feel the same way about our supply in the U.S.,” he told me. “My personal feeling is, if my program is to ensure that your tap water is safe to drink, there shouldn’t be a need for a water store.”

In recent years, drinking water in L.A. County has been found to contain elevated quantities of naturally occurring arsenic and chemicals like chromium-6 from a variety of industrial activities. Generally, officials have said that treatment prevents these chemicals from reaching residents’ taps, or that the level of contamination is too low to affect health.

O’Keefe insists the water delivered to people’s homes is safe. In its annual water quality report released in April, the L.A. Department of Water and Power said its water met and surpassed most federal and state water quality standards. “Your water coming out of your tap is just as good if not better” than bottled or filtered water, said Albert Rodriguez, spokesperson for the department.

Greg Kail, communications director at the nonprofit American Water Works Association, a membership group for water utilities and others working in the field, points out that utilities are required by federal law to tell customers when contamination exceeds legal limits. “In the United States, we have very good water quality,” he said. “It’s important that the customers know.”

“My temperature always rises when we talk about these [water stores],” says Jennifer Clary, the California water program manager at Clean Water Action, an environmental nonprofit. “If people want water that has better flavor, I can understand it, but it would certainly be much less expensive if they just put a point-of-use filter on their faucet. … If they’re worried they have something in their water they want to get rid of, they need to buy a filter that actually gets rid of it.” Clary worked with the California legislature to craft a 2007 law that more tightly regulates water vendors.

The Environmental Working Group and the Natural Resources Defense Council, two nonprofits that work on environmental health, also generally recommend that residents stick with tap water and install filters on their faucets if they’re concerned about contaminants.

David Andrews, a senior scientist at EWG, notes that reports on L.A.’s water show contaminant levels below legal limits. He says that filtered water purchased in large containers is similar to water filtered at home, just more expensive. Mae Wu, an attorney with NRDC’s health program, agrees, adding that most customers receiving water from big municipal systems like L.A.’s can rely on getting clean water from their faucets.

Still, Andrews says that some chemicals in public water supplies can go unreported. “One of the things we’re concerned about are unregulated contaminants, contaminants that may not be tested for,” he says, such as the likely carcinogen trichloropropane. “It is difficult to discern what are concerning test results, what’s not.”

But those kinds of contaminants can make their way into filtered water as well. Most water venders, like Wateria, start the filtration process with tap water, rather than drawing water from a spring, aquifer, or other natural source.

O’Keefe says some water vendors’ filtration systems can actually reduce tap water’s quality. In past years, assessments of water vending machines have found filtered water that has more bacteria than tap water and chemical levels that exceed legal limits. And vended water isn’t always as well-monitored as tap water. Says Andrews, “It’s not always possible to verify that the bottled water is meeting the same standard as the tap water.”

Wateria’s filtration system might be better than many companies’ systems, though. According to EWG’s water filter guide, reverse osmosis systems, like the one Wateria uses, are among the most effective. When maintained correctly, they strain out just about everything — from noxious contaminants like lead, to even beneficial minerals. And a carbon filter, which Wateria also uses, can sift out molecules that reverse osmosis misses, like volatile organic compounds.

Purchasing water at stores or vending machines has a significant cost, though. Tap water costs about three-quarters of a cent per gallon for most L.A. residents. Most water stores in the area charge between 20 and 35 cents a gallon. Wateria sells its purified water for 40 cents a gallon at most of its stores, and plans to raise prices by five to 10 cents this summer.

Oregon, who gets free filtered water as a Wateria employee, says her family consumes about 30 gallons each week. If she were a customer, that would cost her $12 a week. If she got her drinking water from the tap, it would cost roughly $12 a year. A Wateria customer who consumes as much as Oregon would be paying a premium of more than $600 annually.

While some critics question the need for filtered water companies like Wateria, there certainly is a demand. Currently, 1,171 retail water facilities have licenses to operate in the state, according to the California Department of Health, which regulates them. Nearly 40 percent of L.A. residents buy bottled water.

Bottled water advertising has been criticized for targeting people of color. Latinos are a particularly attractive demographic for bottlers and vendors, given that water stores and delivery services are ubiquitous in Mexico and Central America.

In a 2011 survey of parents in the United States, about 20 percent of Latino respondents said they gave their children only bottled water — and not tap water — to drink, while just 10 percent of white respondents did the same. Latino parents reported spending a median of 1 percent of their household income on bottled water, up to a high of 12 percent, while white parents spent a median of 0.4 percent of their income on bottled water, up to a high of 6 percent. (The study found that black parents relied on bottled water more than both Latino and white parents.)

It’s understandable, experts say, that historically marginalized populations — like Latino immigrants — would distrust public agencies’ claims about water safety and choose to rely on bottled water instead. “In Mexico, tap water can be hit or miss,” says Abel Valenzuela Jr., a professor of Chicano studies and the director of UCLA’s Institute for Research on Labor and Employment. “It’s uneven in terms of where you get it and what’s in it,” he says. “And then, when you add up Flint and all the media exposure related to that, it makes sense why poor folks would prefer bottled water even in the United States, where you don’t have the same sorts of problems. Or, at least they tell you we don’t have the same sorts of problems.”

There’s also a taste difference, says Valenzuela, which is the main reason he and his family buy filtered and bottled water.

A mural in a Wateria store. (Emma Foehringer Merchant).

Oregon says most of Wateria’s in-store employees are native Spanish speakers like herself. Many of the neighborhoods in which Wateria stores are located have a high proportion of Latinos. And Wateria is considering expanding to Texas, a state trailing only California in the size of its Latino population.

But Latinos reportedly own few of the water stores in the L.A. area. A 2004 Los Angeles Times article reported that “virtually all the water stores in Southern California are owned by Asian and Middle Eastern immigrants.”

Edward Park, a scholar on race relations in L.A. who teaches Asian Pacific American Studies at Loyola Marymount University, says Wateria is among a number of Korean-owned businesses filling niches in Latino communities, which he says are often underserved by mainstream retailers. He notes that there’s a “dimension of inequality in terms of the migration streams that are bringing folks into these communities,” meaning that some immigrant groups, including many from Asia, may get better access to capital and more support for entrepreneurial ventures in the United States.

But according to Park, who is Korean American himself, the “political volatility or cultural volatility” that has existed between other demographic groups in Los Angeles is less present between Latinos and Asians.

Los Angeles — like all major U.S. cities — has a history of strained race relations. As the demographics of the city have shifted, tensions have changed, too. At times, conflicts in the city have revolved around the high proportion of local businesses owned by Koreans and Korean Americans, and how those business owners interacted with their neighbors.

In 1992, riots roiled L.A. after white police officers were acquitted of the beating of Rodney King, a black man, and a year after a Korean store owner shot dead Latasha Harlins, a black teenage girl. Rioters looted or destroyed about 4,500 stores, more than half of which were Korean-owned or -operated. All told, damage to Korean businesses amounted to about $500 million.

Asian-American historian Shelley Sang-Hee Lee writes in a 2015 article that the Korean community’s “expansion into business ownership was striking: By the time of the [1992] riots, in Los Angeles County, one in three Korean immigrants operated a small family business. … Twenty years after the riots, Korean Americans still dominated mom-and-pop stores in South Los Angeles.”

According to Valenzuela, L.A.’s history is full of entrepreneurial immigrant groups finding “creative ways” to make money by marketing to other demographic groups. That has led to tensions in the past, but he doesn’t see the same type of racial friction around water stores. “These Korean entrepreneurs … have nice, niche inroads, and are probably making lots of money,” he says. “Lots of people probably buy this water.”

A lot of people do, collectively purchasing hundreds of thousands of gallons a month from Wateria. The company will likely add several more California stores to its empire this year.

“He doesn’t give up. He’s always thinking,” Choi says of her father. “He’s a very good engineer. Very smart.”

“Not smart,” counters Kim, laughing.

Choi insists: “Very smart! Oh, very smart.”