A Lyft car idling at every stoplight, a smartphone in every hand — and an eviction on every block.

Few cities have seen as much disruption as San Francisco has over the last 10 years. Once a hotbed of progressive political activism and engagement, the city is being remade in the image of the booming tech industry, headquartered in Silicon Valley to the south.

Rents in some of San Francisco’s most desirable neighborhoods have doubled in a year. Apartment construction has exploded in order to absorb the new residents. The city is developing so rapidly that Google’s streetview photos from 2011 are already well outdated.

The local government has embraced the disruption. Longtime residents, meanwhile, talk about fleeing or saving their city as though a hurricane is coming. But the hurricane has landed.

The storm has brought a surge of tech-driven initiatives designed to supplant services that have traditionally been viewed as public domain. Where downtown urban planning failed, city leaders hope a new Twitter headquarters and other tech outlets will transform a long-troubled business district — and they’re offering up the tax breaks to make it happen. And on the streets, Google and other companies now run their own, very private version of public transit: a fleet of unmarked buses that shuttle the tech class to and from jobs at corporate campuses south of the city.

San Francisco may be an outlier in this trend. But as goes California, so will go the rest of the country. There are lessons to be gleaned from Detroit’s recent bankruptcy, but there is also much to be learned from San Francisco’s recent influx of tech cash. This place is redefining what public and private really mean in all civic spaces — and the implications are not as bright, shiny, and truly shareable as the tech blogosphere would like you to believe.

Last week, one blogger asked, “What if Google bought Detroit?” Well, we know what if: It would make another San Francisco.

Much has been made of Silicon Valley’s private bus system lately because there is much to be made. The private shuttles ferry upwards of 35,000 workers each day between San Francisco and the sprawling tech company campuses 40-50 miles south. That’s about 35 percent of Caltrain’s ridership, and 17 percent of the number that rides the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) system.

They may use the city’s public bus stops, but these are no ordinary buses. They are pure, gleaming white, unsigned and completely anonymous. Riders flash their work IDs to gain access to these luxury shuttles, each outfitted with wifi, of course.

“Sometimes the Google Bus just seems like one face of Janus-headed capitalism; it contains the people too valuable even to use public transport or drive themselves,” Rebecca Solnit wrote in an essay at the London Review of Books. “Right by the Google bus stop on Cesar Chavez Street, immigrant men from Latin America stand waiting for employers in the building trade to scoop them up, or to be arrested and deported by the government.”

Last summer, San Francisco design firm Stamen did the gumshoe work of mapping the private bus lines that run between the city and Silicon Valley. You can see the results of their work in the infographic below. In the year since Stamen completed its research, these routes have likely expanded.

StamenClick to embiggen.

Of course, everybody wants a piece of that action. The startup RidePal promises to deliver “the Google shuttle experience” to companies looking to “recruit and retain top talent.” Another private bus service, Leap, proudly declares on its website: “San Francisco, we’ve built a better bus.”

But when these buses use public bus stops, they often screw up schedules and force public-bus passengers to get on and off at different stops or in the middle of the street. They block bike lanes and crosswalks, back up traffic, and don’t pay a dollar to the city.

This week, the city finally laid down the gauntlet on the buses — kind of. A new proposal would restrict the private shuttles to a network of about 100 city bus stops, require them to obtain permits, and pay some kind of fee — yet to be determined. As Bill Bradley writes at Next City, this all basically amounts to “asking the shuttles to play nice” with the public.

This comes about a month after a Yahoo bus nearly ran into a group of anti-gentrification protesters.

Perhaps nothing revealed the split between public and private services here more clearly than the recent transit strike, when BART workers shut down the regional transit system for four days to protest low wages and safety issues. While BART’s regular ridership — especially the 39 percent who are low-income — struggled to find another way to work, San Francisco’s tech workers just hopped onto their usual private coaches.

Others raged against public services altogether.

One particularly free-market-minded tech writer, PandoDaily’s Sarah Lacy, was primarily concerned with the strike’s impact on the city’s downtown business corridor, the one revitalized by Twitter and the like.

“Like it or not, software is eating the world and Silicon Valley is eating the Bay Area. Better to make friends with it and find a sustainable way to coexist than keep fighting,” she wrote. Lacy then went on to hope tech would “disrupt” BART — not to make public transportation better for everyone, but for the benefit of those Twitterers and the tech industry at large, which she argues is “a meritocracy” that “is sort of directly opposite to unions” to which BART workers belong.

During the BART strike, startups salivated at the chance to make some cash. Rideshare company Avego bought the website Bartstrike.com and advertised constantly on social media before and during the strike, offering low-ish-cost rides for regular folks, and helicopter airlifts to those who could afford them. According to the company, nine people took those helicopter rides.

A crisis for San Francisco’s working class became a business opportunity for its tech class.

Avego

Where the public infrastructure is broken, there has been tremendous opportunity for private startup efforts. Tech begets more tech. Uber, Lyft, Sidecar, and other transportation disruptors would not have gotten a foothold here were it not for a pervasive private car culture and limited rail and bus systems.

But a proliferation of private services means fewer customers using public ones — and, in turn, less public investment in those systems. As another potential BART strike looms, many people are worried, again, about how they will be getting to work. But Silicon Valley will be just fine. The Bay Area’s tech workers didn’t disrupt BART, or lobby for it. Many don’t even use it — because they don’t have to.

In cities, public transportation is often discussed as a great equalizer. In San Francisco, it’s become the dividing line. But it’s not the only one.

San Francisco is a beautiful meeting place for people of every race, creed, sexuality and economic background who are rich now.

— Jesse Thorn (@JesseThorn) July 24, 2013

San Francisco home prices are still rising faster than anywhere else in the country. (Nearby Oakland and San Jose are No. 2 and No. 5 on that pricey list, respectively.) The Wall Street Journal attributes the rise almost entirely to the tech industry.

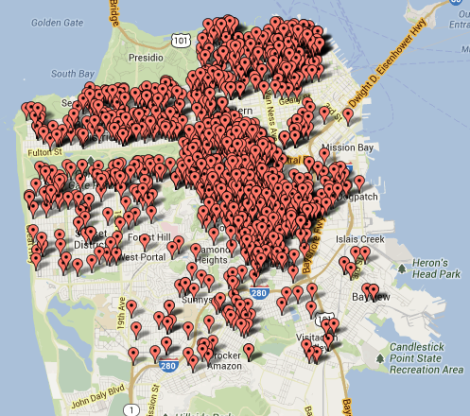

Looking to cash in, more and more San Francisco landlords are conducting “Ellis Act evictions,” which allow them to bypass rent control by kicking every last tenant out of a building.

But the law works like this: Evict the whole building, but you have to keep it empty for up to 10 years. It’s the bizarro version of a foreclosure crisis: Ellis Act evictions have almost doubled over the last year or so, to a rate of more than two each week.

San Francisco may be booming with dense smart development, but it is also full of empty homes.

Brian WhittySan Francisco Ellis Act evictions, 1997-2013

This week, tech gave a little something back. On Wednesday, Google announced that it would be putting up $600,000 over two years to fund wifi networks in 31 of San Francisco’s parks, plazas, and recreation centers — nearly 40 miles north of the tech giant’s Mountain View headquarters.

San Francisco Mayor Ed Lee said this is a “great example” of “public-private partnerships [that] are key to the delivery of better services for our residents in the 21st century.” Another elected official said the wifi would “help bridge the digital divide.” The San Francisco Chronicle called it “Google’s gift” to the city.

But for many residents, this “gift” is too little too late — or worse, just another driver of the gentrification that is chasing lower and middle-class people out.

San Francisco’s tech influx has reached a tipping point. People are pissed. There have been personal essays, delightfully ragey, NSFW music videos, and a fair bit of graffiti.

“A group of gentrification protesters unleashed their rage on a piñata of a Google Bus, an act that seemed at once sadly impotent and uncomfortably close to violence,” Chronicle tech columnist James Temple wrote in June.

Temple defended the tech industry as best he could, dispensing with all substantive critiques to conclude: This is just how this city rolls. “San Francisco changes because the world changes. It was formed in a gold rush and reshaped by every one that followed.”

But this libertarian, gold-rush mentality is not what we had come to expect from progressive San Francisco.

At last week’s regional government meeting, officials finally passed a comprehensive plan to reduce the Bay Area’s greenhouse gas emissions by 15 percent over the next 20 years, in part by investing in public transportation and building more densely. For hours, suburban Bay Area residents took to the mic to declare, in some form or another, that we don’t need buses, that cars are nice, that things are just fine. A few warned that they planned to wage a revolution.

This, coming from people who, like Google, have fled the urban center. While San Francisco is now home to about 1,800 tech companies, many of the largest escaped for massive, gated, concrete bunkers in the suburbs, far from San Francisco business taxes, public transportation options, and the general public itself. In other words, Bay Area tech companies aren’t just taking advantage of broken public infrastructure — they worked hard to break it.

But in moving to the burbs, Google, Facebook, et. al. didn’t count on the modern lifestyle preferences of their young workers. In a perfect reverse of old geographic lifestyle trends, many urbanites now leave every day for work in the burbs, and then return to their homes in the city each night. It’s a trend in cities across the country, but perhaps nowhere else has it taken such a visible toll on a place’s civic and physical infrastructure as it has here.

Entrepreneurs and techies delight in the idea of “disrupting” business as usual. But it’s worth considering what things might be like if tech companies and their employees were less interested in walling themselves off from the rest of the world, and instead worked for the collective good. Sometimes these companies will buy us a parklet or some free internet access. But we do ourselves and our fellow citizens a disservice if we equate these efforts with real innovation in our cities and our lives.

Case in point: Google hosted a fundraiser for climate-denying Oklahoma Sen. James Inhofe earlier this month. Progressives seemed surprised — and angry. Google’s motto is, after all, “Don’t be evil.” But the company also has business interests in Inhofe’s state.

Protesters from Forecast the Facts and 350 Silicon Valley descended on Google’s suburban campus this week with a petition signed by 50,000 people, but Google didn’t want it.

“Google has decided to reject the petition. Instead, the receptionist suggested we submit a business proposal.” -protest leader brad Johnson

— Kiera Butler (@kieraevebutler) July 24, 2013

So, sure, let’s pressure these companies to be better, but let’s also remember that Google has done a lot of evil things. It is a company with a profit motive, after all, and the presumption that somehow Google wouldn’t help out a climate-change-denying senator just because the company has told us it won’t “be evil” reveals just how far down this trap we have already fallen.

This is the other side of an influx of creative class investment in our cities and our lives: The “prosperity” doesn’t really trickle down. It is larger and more insidious than the immediate ramifications for a gentrified neighborhood, or the people waiting for the Google bus to clear out so they can catch a public one. It is a breakdown of the social contract, a shift of civic responsibility from citizens to business.

And it is a very, very slippery slope.