On Tuesday, March 24, an overturned fish truck turned Seattle into a parking lot, giving residents of this traffic-clogged city yet another reminder of the pitfalls of a transportation system built almost entirely around automobiles.

The truck was headed south on State Route 99 carrying a load of frozen cod when it tipped, blocking all southbound lanes of one of just two main north-south arteries through the city. (This is the same highway that will someday run underneath Seattle if the tunnel-boring machine Bertha can ever be repaired.) That was at 2:23 p.m., as people were beginning to leave jobs downtown and tailgaters were rolling in for a Sounders soccer game at the nearby CenturyLink Field — an event that was projected to draw 39,000 fans.

As city crews struggled to right the truck and move it from the road, traffic backed up as far as the University District, five miles away, snarling Interstate 5 and secondary streets throughout the city. By the time the highway was finally reopened, at 11:37 p.m., the wreck — plus three more accidents downtown, including one involving a bus and a pedestrian, and a police manhunt in the nearby International District — had stranded commuters in traffic for hours. Local media dubbed it the Seattle Standstill.

[grist-related-series]

The fish truck incident may have been a particularly epic example, but the Standstill is a regular feature in this city, which, according to TomTom, a company that makes GPS devices, has the fourth worst traffic in the country, worse than New York, Miami, and Washington, D.C.

“What’s surprised me most is the fragility of the system,” says Scott Kubly, who took over as the city’s transportation director last July. “Almost every day there’s a crash that impacts our system, and ends up snarling traffic for everybody.”

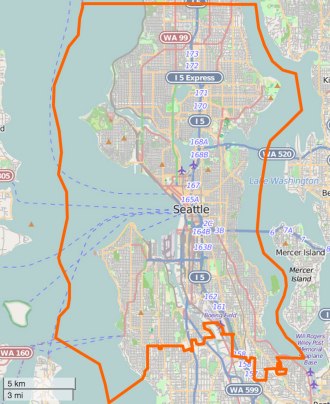

Part of the problem is simple geography. Seattle is sandwiched between Puget Sound and Lake Washington, and pinched by other lakes and water bodies as well. North-south travel bottlenecks at a handful of bridges, as does any travel to suburbs to the east. (To go west, you’ll have to take a ferry, which creates its own set of challenges.)

The other issue is infrastructure, or lack thereof. “Look at San Francisco, Washington, D.C., Boston — they all have very big, strong rail networks, using dedicated or separated access,” Kubly says. “Right now, we have one light rail line from the south, and a couple more on the way. There’s probably not another city in the country that needs to make that kind of investment more than we need to.”

An expanded light rail network is a decade away, at least. In the meantime, Kubly and his colleagues are left to make better use of the city’s existing tangle of roads while tens of thousands of new jobs and residents rush in. To make matters worse, the funding mechanism that has paid roughly a quarter of the cost of maintaining the city’s streets for the past decade is about to expire, leaving officials to wonder where the money will come from.

Seriously, who would want this job?

Seattle’s transportation director, Scott Kubly Ansel Herz, The Stranger

Kubly, 40, is a tall glass of milk — a lanky 6-foot-4, with a hairline that’s beating a hasty retreat and a nose that looks like it’s been broken. (It hasn’t, he says. “My crooked schnoz is all natural.”) He worked with transportation whiz Gabe Klein when Klein was getting the nation’s first bikeshare program up and running in Washington, D.C., then followed Klein to Chicago to help with Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s transportation revolution.

Kubly was working as the president of Alta Bicycle Share in early 2014 when he got the call to interview for the job in Seattle. “I hadn’t spent any time in Seattle,” he says. But the landscape grabbed him, and he was impressed with the city’s commitment to addressing climate change. “Being in a place where elected officials talk about climate change in a positive way, in the sense that we need to do something about it, is really exciting,” Kubly says. Vehicle traffic accounts for 40 percent of the city’s greenhouse gas emissions, more than any other sector.

But it was Mayor Ed Murray who clinched the deal. As a state legislator, Murray played a key role in legalizing gay marriage in Washington. In 2014, his first year as mayor of Seattle, he brokered a deal to raise the minimum wage to $15. On transportation, Murray worked to regulate ride-hailing services such as Uber and Lyft without driving them out of the city completely, and installed a protected bike lane downtown — something that would have been unheard of even a few years prior.

“You have a mayor that may not have the bombastic style that you see around the country with other mayors, but at the same time gets things done,” Kubly says. “As soon as I sat down with [Murray], I was like, yes, I want this job.”

Under Kubly, the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) has laid out an ambitious plan to overhaul the city’s streets. The plan, called Move Seattle, is remarkable in many ways, but none more than this: While it includes maintenance and repair of existing roads, and upgrading bridges to make them earthquake-safe, there are virtually no new accommodations for cars. Instead, it is a plan to more efficiently move people around the city by bus, transit, bike, and on foot.

Here’s a sampling of the initiatives contained therein:

- Seven to 10 “multimodal corridor projects” — that is, travel corridors that incorporate designated space for bikes, buses, and other mass transit.

- Seven new “bus rapid transit” corridors that will hustle riders in and out of the city in designated lanes, separate from car traffic.

- Easy access to buses that arrive at least every 10 minutes, throughout the day, for three-quarters of city residents.

- A build-out of half of the city’s perpetually underfunded bicycle master plan, including 50 miles of protected bike lanes.

- One hundred blocks of new sidewalks, new crossings at 225 intersections, and safe walking and biking routes to all of the city’s schools.

- Reducing traffic deaths to zero by, among other things, dropping speed limits on residential streets of 20 mph, and 30 mph on arterial streets.

“This is not ideological,” says Hannah McIntosh, the SDOT strategic advisor who spearheaded the planning process. “It’s purely geometry. It’s purely pragmatism. There is simply no more space on our roads.”

Murray’s predecessor, Mike McGinn, a former state Sierra Club leader and avid cyclist, was often accused of bowing to the “bike lobby” and “waging war on cars.” Murray is fond of telling people that “there is no war on cars.” Instead, he talks about moving people around safely, affordably, and efficiently. (Kubly points out that getting more people on buses, bikes, and foot makes life better for drivers as well.)

To do that, SDOT officials say, the city will need to designate separate routes for different modes of travel. A transit corridor, for example, might be placed on an adjacent, parallel street to a bike track, with freight relegated to a third route. “Every street is going to look different,” McIntosh says. “You can’t cram every single use onto every street.”

This may sound basic, but the suggestion that cars are not the first and best use for every street, while other uses are to be shoehorned in where it’s convenient, is something of a revelation here, as it would be in many American cities.

“In a lot of ways, SDOT is way out ahead of [bike and transit] advocates,” says Tom Fucoloro, founder and editor of the Seattle Bike Blog. “We got used to compromising away the dream. Here we have some leaders who just want to go for it. That’s huge.”

Fucoloro also praises the department’s willingness to try new things, and correct course as they go — as it did with the protected bike lane downtown. “Previously, there was a fear of changing the status quo quickly — that you’d create a backlash,” Fucoloro says. “Oddly enough, we’ve found that if you really go big, and if you convince people that you’re going to fix it if it doesn’t work, they’ll support you. People don’t want half-projects.”

But there is one huge hitch to the Move Seattle plan: Over the course of its nine-year lifespan, the city estimates that it will cost roughly $3 billion.

The Second Ave. protected bike lane in downtown Seattle.SDOT

Roughly two-thirds of the cost of this citywide street overhaul will come from the general fund, commercial parking and real estate excise taxes, and grants, McIntosh says. To make up the difference, Mayor Murray and SDOT have proposed a nine-year property tax levy that will raise an estimated $930 million. The levy, which would add roughly $275 to the annual tax on an average home, will need the approval of voters this fall. And while Seattleites have recently shown a willingness to pony up for better transportation — last fall, voters approved a $60 annual car tab to fund additional bus service — signing off on a billion dollars in new taxes will require a leap of faith.

The Transportation Levy to Move Seattle, as the mayor calls it, would replace an existing levy approved by voters in 2006. That levy, called Bridging the Gap, was roughly a third the size of Move Seattle, and billed largely as a pothole-filling measure. It was sold to voters with signs posted next to battered roadways that read “Fix This Street.” Many of those streets have yet to be fixed.

And then there are Move Seattle’s outsized goals. Pedestrian and bike advocates, for example, say that the Safe Routes to School program needs $40 million; the Move Seattle levy earmarks just $7 million. The bicycle master plan says it will cost $200 million to build out half of the city’s bike network; the levy calls for just $85 million. McIntosh says SDOT will save money by including bike infrastructure with other road improvement projects, and by rolling out bike lanes and other projects using temporary, or “less than final” materials.

“There’s an element of trust here,” says Fucoloro, the bike blogger. “You’re basically trusting them that they can roll out all these bike lanes at reduced cost — but also that we can get all the [matching] grants that are built into the [Move Seattle] plan.”

And keep in mind that Move Seattle is something of a stopgap, designed to keep the city humming along until a real solution — a rail system — arrives. On that front, funding becomes even more tricky, because plans for a light rail system are regional, and will therefore require buy-in not just from Seattleites, but also from the residents of surrounding suburbs.

The region has a spotty record on approving funding for mass transit. In 2007, King County, which encompasses Seattle, and adjacent Snohomish and Pierce counties voted down a measure that would have funded light rail and streetcars. Supporters got a measure passed the following year, but it was scaled back. There was a similar miss, then hit, in the mid-1990s. In 2011, after more than a decade of bickering, even Seattle voters supported the $2 billion car tunnel under the city, knocking out more transit-centered proposals.

Sound Transit, the authority that oversees regional rail development, is queuing up for its next big push, called Sound Transit 3. The $15 billion plan will expand the light rail system connecting the city to surrounding communities, and build critical lines within the city itself.

Martin Duke, editor of the Seattle Transit Blog, is confident that voters will approve Sound Transit 3. While there has been much debate over what led to the demise of various transit measures over the years, Duke says they tend to succeed during presidential election years, which bring out younger and more progressive voters.

But to raise that kind of money, Sound Transit will need approval from not only the voters, but the state legislature as well, which limits the amount that the region is allowed to tax itself. Particularly troublesome is the state Senate, which is dominated by Republicans who are often hostile to the interests of the state’s largest, distinctly left-leaning urban area.

The legislature is currently hammering out a transportation package, which may or may not give Sound Transit the necessary taxing authority.

Daniel Penner

In the meantime, Seattle transportation officials are cramming more and more bodies into an increasingly cramped space, clown-car style. So far, somewhat miraculously, it has worked. Since 2010, the city has added 26,000 jobs downtown, but thanks to increases in transit ridership, walking, and biking, the number of cars on the roads has remained essentially flat.

And there are more tricks where those came from. Coming this summer: a new streetcar line, two new bus rapid transit lines, and a 15 percent increase in bus service paid for by the new car tab. The Car2Go car-sharing service recently announced that it is expanding its range to include more of the city. And those not inclined to drive what my kids call “Snoopy cars” will soon have the option of rocking a BMW or MINI Cooper, when DriveNow arrives in Seattle later this year. Bikeshare is taking off, too.

Still, without a rail network, one wonders how long the city can hold back the tide. And even at current traffic levels, all it take sis one overturned truck, or one crash, to bungle the entire system.

Scott Kubly tells the story of a recent visit to Seattle by former New York City transportation chief Janette Sadik-Khan, who oversaw a dramatic reshaping of that city’s streetscape. Sadik-Khan was scheduled to talk that evening, but had some time to spare beforehand, so Kubly took her for a tour of the Seattle. By car.

He was driving her back to her hotel so she could prepare for her talk when traffic downtown slowed to a standstill. “We stayed on same block for like 15 minutes,” Kubly says. “I got on the phone, called in, and said, ‘What’s going on?’” Near as SDOT could tell, there had been a crash on I-90 in Bellevue, 10 miles from where they sat. That wreck had clogged both I-90 — the main route out of the city to the east — and I-5 through town, blocking all the on-ramps in the city, and thus all the streets downtown.

Eventually, Sadik-Khan got out and walked the last block to her hotel. “It was going going to take 20 minutes,” Kubly says.

“Ten years ago, 15 years ago, Seattle was at the forefront of transportation,” Kubly says. “If you would have said 10 years ago that it would be more pleasant to bike in midtown Manhattan, or in downtown Chicago, than downtown Seattle, nobody would have believed you. Seattle, you know — it’s like this little utopia in the Pacific Northwest, right?

“But people are catching on that we need to make investments in different types of transportation so people can make choices in how they get around,” Kubly continues. “Houston has a huge light rail program. Dallas has a huge light rail program. L.A. is building more rail than any city in the country.

“Seattle is waking up and saying, ‘Holy cow, we need to catch up.’”