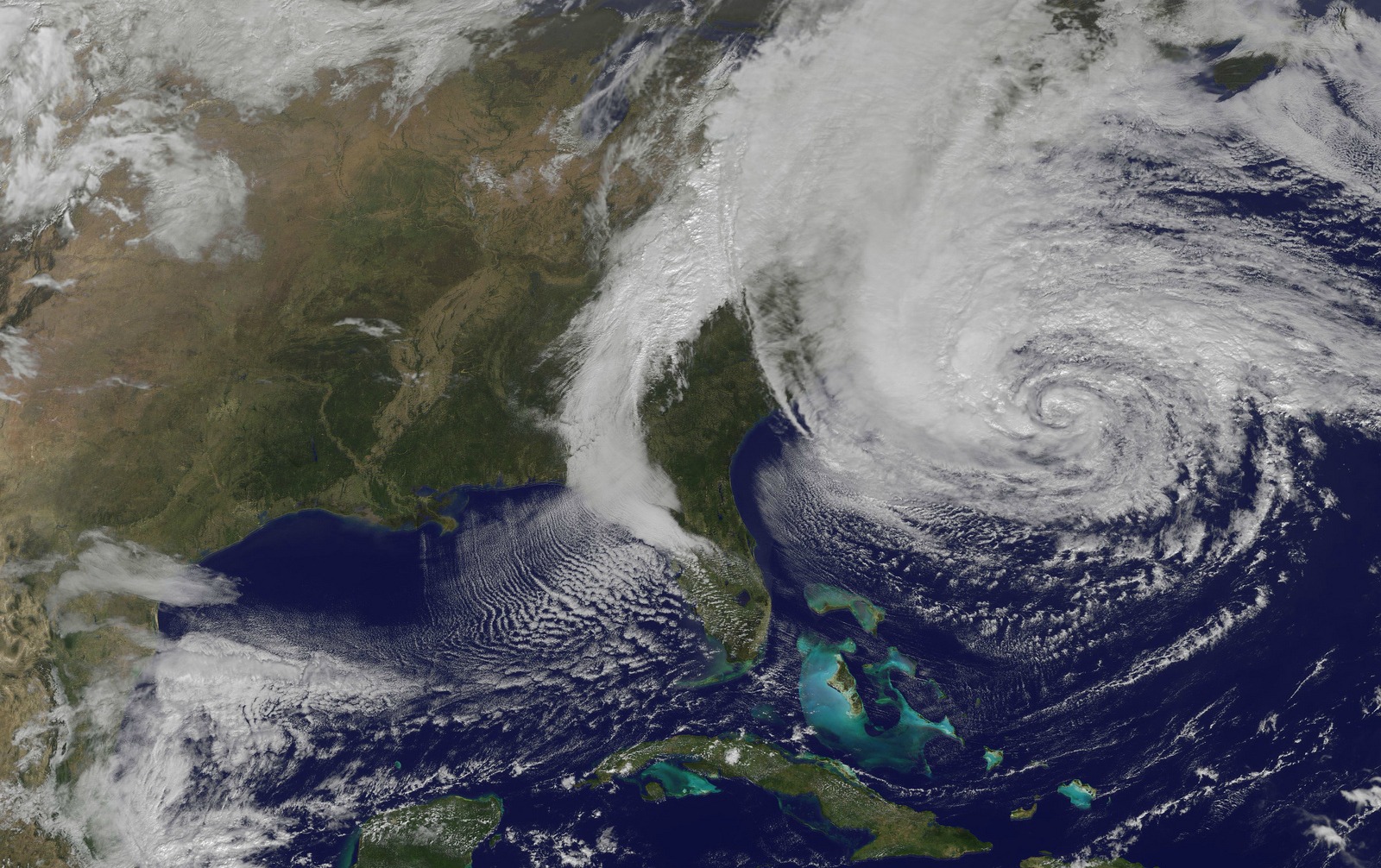

NASA GOES ProjectHurricane Sandy

One year ago today, Superstorm Sandy was just a twinkle in meteorologists’ eyes. The storm, which kicked up from a low-pressure area in the Caribbean Sea on Oct. 22, wouldn’t become an official hurricane for two days still. Even after it gained official hurricane status, raking across Jamaica and Cuba and soaking the Bahamas, U.S. weather models predicted that it would spin off into the North Atlantic and peter out, as most such storms do.

But Sandy did something different. After briefly losing steam, it rolled northward along the Eastern Seaboard and then veered left like a car that had just lost a wheel, barreling into the Jersey Shore and pushing storm tides through the streets of New York City. When the skies finally cleared and Wall Street opened back up, at least 159 people were dead, and the storm had caused $65 billion in damages and relocated the city’s rat population.

It was a shocking turn of events. Hurricane Irene had given New York a good scare (and New England a thorough drubbing) in August 2011, but the last time a major hurricane had hit the city was 1938. That storm killed 600 people, according to a New York Times report. But after decades of relative quiet, many New Yorkers doubted it would happen again. It’s easy, in those canyons of concrete and brick, to imagine that nothing will change.

There was one man, however, who saw Sandy coming. Nicholas K. Coch, a professor of coastal geology at Queens College, had been warning for almost two decades that a major hurricane could take out New York. The habit earned Coch the nickname “Dr. Doom” — a sobriquet that he didn’t take kindly to. (“No serious scientist wants to be called Dr. Doom,” he says.)

Professor Nicholas K. Coch

Coch, who measures in at just over 6 feet 7 inches, calls himself a “forensic hurricanologist.” In 1989, he was part of a team of geologists who traveled to South Carolina to see the aftermath of Hurricane Hugo. “I looked at Hugo and said, ‘This is the type of hurricane that’s gonna hit Long Island,'” he says.

Digging back through the historical records, he found that his fear was well-founded. In addition to the 1938 storm, Coch found records of other hurricanes hitting the Northeast as far back as 1635. While northeastern hurricanes are less powerful than southern storms, they tend to be larger in area, and faster moving. When the 1938 storm made landfall on Long Island, it was moving 50 miles an hour; a typical southern hurricane travels about 15 miles per hour. The storm surged all the way across New England and into Canada.

By the mid-90s, Coch was warning that New York was due for another Big One. “People laughed at me,” he says. “They just thought that was the funniest thing they ever heard.”

But the more he learned, the more Coch believed the city was vulnerable. New York City is built atop bedrock, so rain that falls on the city stays on the surface, creating flash floods long before the heart of the storm arrives. When the storm does come, it brings a new surge of water, this time from the sea. “New York is a water city,” Coch says. “There’s really no place else in the world that has a more complicated water system.” In New York Harbor, there are three different tidal systems at work.

Add a massive storm surge to this slurry, and things get wet in a hurry. Witness what happened with Sandy.

Coch is in the process of publishing what he calls his “opus” on New York City’s hurricane vulnerability; he hopes it will be published next spring in the Journal of Coastal Research. The main message of the paper, he says, is that New York has only gotten a taste of what is to come. After all, Sandy wasn’t even a technically a hurricane when it made landfall: It had been downgraded to a post-tropical cyclone.

CyclonebiskitThe bizarre track of Superstorm Sandy.

“Sandy was not the Big One,” he says. “Sandy was a freak, caused by an extremely rare confluence of events.” One of those events was the massive “blocking ridge” that swatted the storm west into the city, rather than east into the North Atlantic. (Some have credited melting Arctic sea ice for creating that ridge.)

Sooner or later, Coch says, a major hurricane will barrel up the East Coast and hit New York broadside. Long Island juts out into the Atlantic at a nearly right angle, he points out, and will be the first significant topography a storm like that encounters on its path northward. Manhattan sits right on its heel.

Will New York be prepared? Coch says Mayor Mike Bloomberg’s climate resiliency plan is “a good first step.” Still, he doesn’t have much faith that our fixes will be long-term: “Americans are incapable of strategic mitigation — that is, solving the problem, versus fixing it over and over again,” he says.

Making matters worse, of course, is the fact that these storms are getting bigger. “With climate change, we are going to see water levels like we have never seen before,” Coch says. “We can’t go by past experiences.”

But at least there’s this: After witnessing the destructive power of Irene and Sandy, people seem to be taking Coch more seriously. “After Sandy, somebody asked me, ‘Do people still call you Dr. Doom?'” Coch says. His reply: “No, but they’re calling me quite often now.”