The whole better-greener-more-awesome-cities movement has a problem: We haven’t found a good name for it. Sustainable cities! The term brings to mind such mundanity as energy audits and transit routes. Resilient cities! The notion requires us to consider, first, what horrible shit is coming down the pike. Carbon-neutral cities! Ugh. Don’t get me started on that one.

Enter University of Virginia urban and environmental planning professor Tim Beatley with the solution, FINALLY. Here he comes, with the delivery. Wait for it…

Wait, come back! It’s better than it sounds! Biophilic cities are places where animals and plants and other wild things weave through our everyday lives. The name comes from “biophilia,” E.O. Wilson’s theory that humans have an innate connection to other living things, because we evolved alongside them. It’s futurism with a paleo twist: An effort to create human habitat that can also host a menagerie of wild creatures — and not just for their sake, but for ours.

The idea seems to be catching. In October, Beatley helped launch the Biophilic Cities Network, which includes eight cities worldwide, and there are more to come. “Reducing your emissions, hitting people over the head about turning the lights off — we need to do those things,” Beatley says. “But to motivate people I think we need that vision of where we want to go, not just how much less we want to consume of something.”

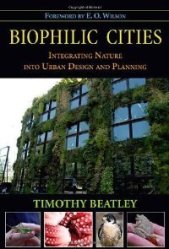

Beatley stopped by Grist HQ on a recent swing through Seattle promoting his new book, Biophilic Cities: Integrating Nature into Urban Design and Planning. Here are a few snippets from our conversation, which covered aerial urban trails, our odd relationship with the natural world, and cities that are far greener than the this here emerald one.

Q. How is a biophilic city different than a “sustainable” city or a “green” city?

Tim Beatley.

A. There’s lot of overlap, to be sure. A biophilic city must be resilient and sustainable and all of those things. But it ought to be a dense, rich, urban life in close contact with nature. The idea grows from the theory that we have coevolved with the natural world, that we’re carrying our ancient brains, and we have an innate need to connect with nature.

Q. I know spending time outdoors is good for us, but do people really need nature? It’s like broccoli, right? It’s good for you, but that’s why we have multivitamins.

A. Can we survive? Sure, we can and have. But you wouldn’t necessarily be very happy or very productive or very creative. In the last two to three years, there’s been an increasing set of studies that show how much we benefit from having nature around us. It affects our mood. We score more highly on creativity tests when we have nature around us. In a more natural setting, we are more likely to take longer making economic decisions. We’re likely to be more generous. We’re likely to be better human beings … if we have everyday nature around us — not a place where you go visit on a holiday, but nature that is a meaningful part of our everyday life.

Q. Can you give me some examples of cities that have worked nature into the urban landscape?

A. Singapore represents an example of greening that can take place in a very dense city. The city is creating policies to promote creative vertical greening — green balconies, green rooftops, green walls. It has also created this network of walks, some of them elevated canopy walks (pictured at top).

Vitoria-Gasteiz, the capital of the Basque country in Spain, is in many ways the perfect model. It’s a dense, compact city, but it’s also close to nature. It has this fantastic green ring that encircles the city. There’s a historic shepherd’s trail where people can walk. Now the city is creating an interior green ring, bringing nature into the dense urban core.

There’s Oslo — two-thirds of that city is in protected forest. There’s a very extensive network of urban trails, and they’ve even designed public transit routes and stations to help people get out to that public forest. They’re densifying the remaining third of the city and daylighting and restoring the eight major rivers that connect the forest and the urban core.

Q. Goodbye, I’m moving to Norway.

Q. Goodbye, I’m moving to Norway.

A. We have four partner cities [in the Biophilic Cities Network] in the U.S., too. In Portland, they’ve created green streets that are bringing some amount of nature in to the city while also collecting and cleaning rainwater. San Francisco has been pioneering how to use little spaces like parklets. Organizations like Nature in the City are pushing butterfly habitat restoration and trying to find ways to link these small spaces into a network of habitats.

Q. So this is both nature for people’s sake and for nature’s sake?

A. It can be. There’s a recent study that’s shown a remarkable amount of biodiversity in cities — the idea that cities can be biological arks is very true. In many parts of the world, cities harbor a huge number of species that have been lost in non-urban settings. In places like the Netherlands, where it’s such a human-altered landscape, it’s not a huge surprise that you find more nature in that cemetery in the city than in any of the surrounding countryside. It’s not quite that way here, but in New York City, you find remnants of old-growth forest — the largest poplar tree is in Brooklyn, because all the others were cut down in the era of farming and plowing and converting land.

As we become a more urban planet, those urban environments need to harbor greater and greater amounts of biodiversity. We still need to worry about conserving rain forests and coral reefs, but cities have to be part of the habitat for nature — for us, ultimately as well.

Q. Throw climate change into this mess.

A. Almost everything we do to make city biophilic will have very significant benefits in terms of enhancing resilience when you think of droughts and heat waves and urban heat island effects. These things can also impact climate change writ large: Sea-level rise, increasing summer temperature highs, all these things can be positively impacted by introducing more nature to cities.

Q. And it’ll help us stay sane through the apocalypse as well?

A. There’s a fellow named Keith Tidball who is writing about “urgent biophilia.” He argues that it’s at these times of crisis — the hurricane, the earthquake — that we need nature even more. It is therapeutic, recuperative. In Christchurch, New Zealand, for example, which is recovering from the pair of earthquakes, greening the rubble and other green efforts are helping that city recover from that incredible trauma.

We know that nature helps to bring us together, helps to promote socializing, formation of friendships, building a sense of place and a commitment to place. And all of those things can help us be more resilient in the face of a series of potential future shocks, economic and environmental. Nature can do that.