When a hurricane slams into the Jersey Shore, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) gets the call to pick up the pieces. When a tornado lays waste to an Oklahoma community, guess where the phones start ringing? FEMA. And when a foot and a half of rain falls around Boulder, Colo., sending hundreds of homes into the drink? Yep: FEMA again.

But not all FEMA’s shit storms are of the weather variety. When angry ratepayers blew up their elected representatives’ phone lines recently, Congress hauled in a few of our chief emergency managers. The controversy swirled around rate hikes for property owners covered by the National Flood Insurance Program, which FEMA administers.

“Let me just say, all of the harm that has been caused to thousands of people across the country — [who] are calling us, [who] are going to lose their homes, [who] are placed in this position — is just unconscionable,” Rep. Maxine Waters, D-Calif., told the agency’s director, Craig Fugate, during a recent hearing.

But here’s the thing. As NPR’s Christopher Joyce so astutely pointed out, Waters co-sponsored the law that directed FEMA to raise people’s rates. In fact, it bears her name: It’s called the Biggert-Waters Flood Insurance Reform Act.

Here’s the other thing: While Biggert-Waters contained only passing mention of climate change, it was the first real wake-up call for many coastal residents who had been living with the illusion that, if disaster struck, the federal government would always be there to pick up the pieces. As comforting as that might seem, it is becoming less and less realistic as the mercury, and the waters, rise.

Here’s the story of how we got here — and a few thoughts on how we might get out.

The National Flood Insurance Program was created back in 1968, a time when many private insurance companies found flood insurance too risky. To cover the escalating costs of cleaning up after floods — and to encourage communities to adopt smarter floodplain development rules — the feds created their own insurance program, offering discount rates to convince people to buy in. It may have seemed like a good idea at the time, but over the years, the situation became pretty preposterous, as the government’s cut-rate insurance encouraged building, and rebuilding, in vulnerable coastal areas and floodplains.

“If you’re an 18-year-old and you buy a Ferrari, you’re probably not going to be able to get insurance,” says Stephen Ellis with the budget watchdog group Taxpayers for Common Sense. “Even if you’re a 30-year-old driving a Chevy Cavalier, if you get in an accident, your premiums are going to go up. That doesn’t happen with flood insurance. We had properties that flooded 17 or 18 times that were still covered under the federal insurance program.”

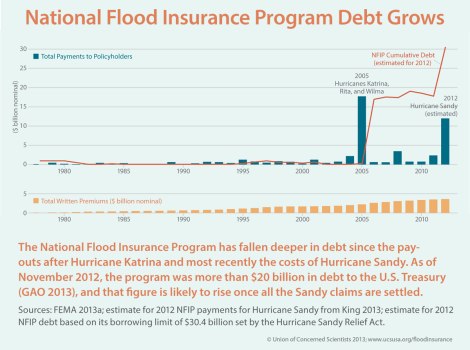

The program plodded along for a couple of decades, usually bringing in about as much money as it doled out to rebuild flooded homes and businesses, but never ferreting away enough of a surplus — a “catastrophic reserve,” as they call it in the insurance biz — to cover a really disastrous year. Then came Hurricane Katrina and her oft-forgotten sisters Rita and Wilma in 2005. The insurance program suddenly found itself $18 billion in debt — and with annual revenues of only $3.6 billion, little if any hope of ever getting back into the black.

Here’s a graph of what that looked like, from a study done by the Union of Concerned Scientists:

Years of legislative wrangling resulted in the Biggert-Waters Act, which, among other things, ordered FEMA to stop subsidizing flood insurance for second homes and businesses, and for properties that had been swamped multiple times. There would be some pain, yes, but to soften the blow, the law directed FEMA to spread out the rate increases over four to five years. Congress also asked FEMA to conduct an affordability study to see how the new rules could be administered without leaving people in the poorhouse — or with no house at all.

That study hasn’t materialized, in part because FEMA has been busy with other things: A little over three months after President Obama signed Biggert-Waters into law, Hurricane Sandy slammed into the Eastern Seaboard, sparking a massive clean-up effort and knocking the flood insurance program even further into the red. By the time all the Sandy pay-outs have been settled, the program will owe the U.S. Treasury close to $30 billion.

Biggert-Waters, meanwhile, rolled on. In October, notices went out to roughly 438,000 policyholders announcing that their rates would be going up, in some cases dramatically. (Nationwide, the federal flood insurance program covers 5.5 million properties, one in five of which receives discount rates, meaning the property owner pays only 40-45 percent of the “risk-based” rate a private insurance company would charge.) Thousands more are living in fear of future rate hikes. The other major piece of Biggert-Waters was a directive to FEMA to redraw its outdated floodplain maps. That means many people who live in vulnerable areas, but are currently outside the official flood zones, may be drawn in.

Now, with complaints rolling in from irate property owners, Washington is doing damage control. Sens. Robert Menendez (D-N.J.) and Johnny Isakson (R-Ga.) are pushing a bill that would delay rate hikes for four years. The bill may come up for a vote this week. Others are pushing for even more dramatic backtracking.

But supporters of the Biggert-Waters reforms, who include budget hawks and insurance companies, as well as scientists and environmentalists, are urging lawmakers not to throw the baby out with the rising bathwater.

“Biggert-Waters was one of the most revolutionary pieces of legislation ever passed by Congress related to insurance,” says Howard Kunreuther, a professor at the Wharton Risk Management and Decision Processes Center at the University of Pennsylvania. For the first time, he explains, the government would be charging property owners insurance premiums based on their level of risk — that is, FEMA would be doing business the way that private insurance companies do.

If the insurance bill reflects the actual level of risk, people are more likely to do things to reduce that risk, like jacking up their homes to keep them above floodwaters. “Biggert-Waters encouraged people to say, ‘I’m going to make my house safer,’” Kunreuther says. That’s good for their homes — and good for the flood insurance program, which is left with the bill when houses are flooded.

To solve the problem of affordability, Kunreuther and his colleagues have proposed a system of vouchers that help people who need help to pay their rising insurance rates — on the condition that they take measures to make their properties less vulnerable. To finance the improvements, the government would offer low-interest loans. And presumably, by the time the work was done, the property owner’s risk, and therefore his or her insurance rates, would have come down substantially. (You can read a more detailed discussion of their proposal here.)

Whether or not this kind of sane reform is possible given the current rate of political backpedaling is an open question. We should have a clearer sense later this week.

In my next post, I’ll look at the broader implications of climate change on flood insurance, and what people are doing about increasing risks from natural disasters.