National governments — especially the American government — are largely paralyzed on climate change. But one message from the U.N. Climate Summit and surrounding events last week was that cities can do a lot to reduce greenhouse gas emissions on their own. They account for most of the world’s population and emissions. And cities, not beholden to rural, fossil-fuel dependent constituencies, often have more political freedom than national governments to address climate change.

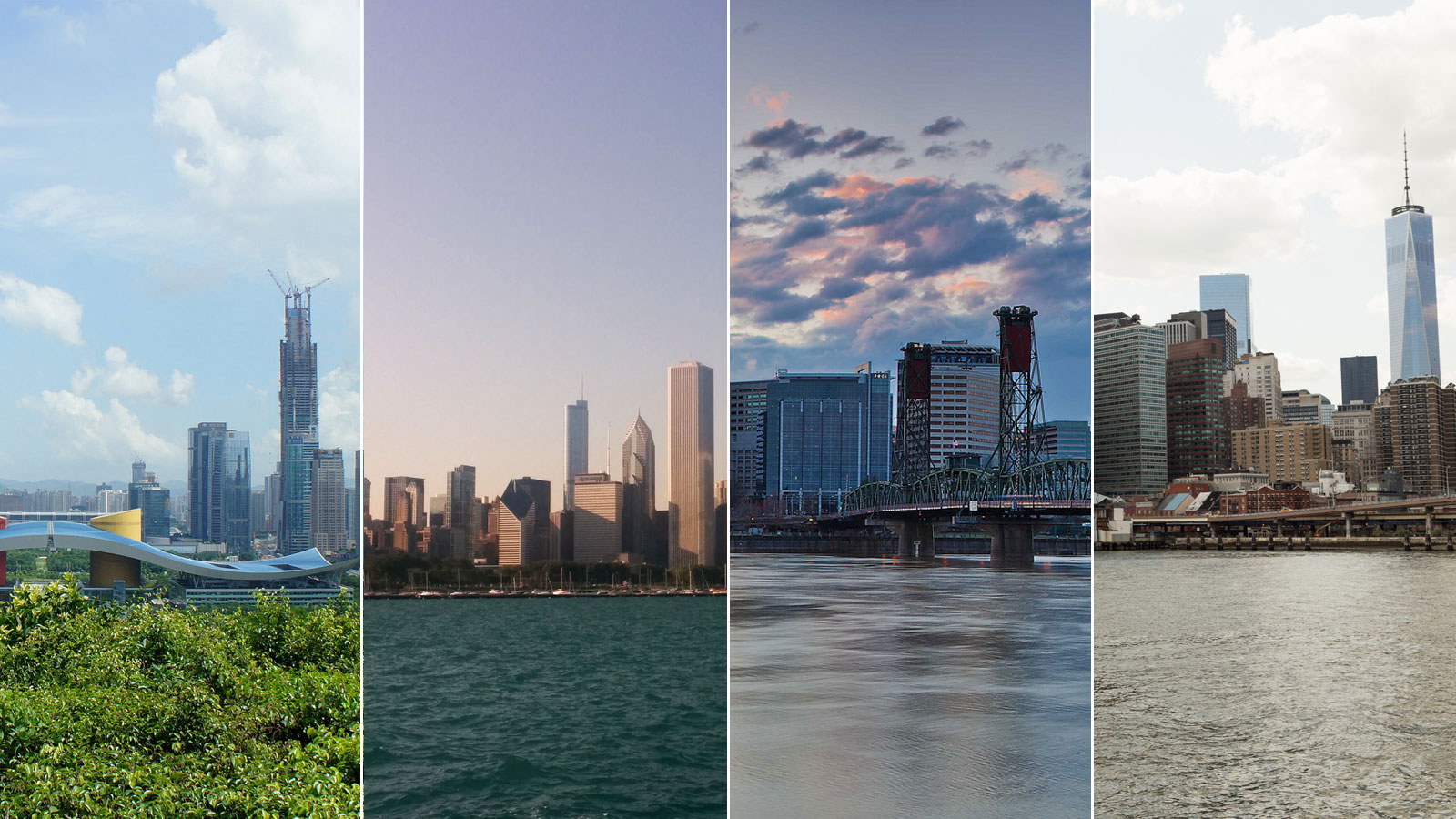

The world’s largest cities are forming organizations to coordinate their efforts and learn from one another. In 2005, the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group formed. Despite the name, there are now 69 affiliated cities from more than 40 countries, accounting for a twelfth of the world’s population. There are 12 member cities in the U.S. Mostly, these are green enclaves like Portland, New York, Chicago, San Francisco, and Seattle. But C40 also includes sprawling Los Angeles and Houston, the country’s second- and fourth-largest cities.

While in New York for the Climate Summit, the mayors of L.A., Houston, and Philadelphia announced a “Mayors’ National Climate Action Agenda,” to set targets in their cities for emissions reductions, and to create or update climate action plans. They are also going to look for ways of offsetting emissions, like tree planting and capturing methane emissions from landfills, and they are going to encourage other mayors to sign on to the initiative. According to Houston Mayor Annise Parker (D), her city has already reduced its greenhouse gas emissions 32 percent since 2007.

In 2009, the percentage of humanity living in urbanized areas surpassed the percentage living in rural areas. Currently 54 percent of people live in cities, and the figure keeps growing. Cities account for around 60 percent of global GDP, 70 percent of greenhouse gas emissions, and 80 percent of the increase in emissions last year. As Roland Busch, global CEO of the infrastructure and cities sector of Siemens, which is sort of like Germany’s General Electric, said before the C40 annual awards dinner in New York last week, “If you want to fight climate change, cities is where the battle must be won.”

Globally, cities consume more energy per capita than rural areas. This may seem counterintuitive to an American who associates urban density with energy efficiency. But North America and Europe, where economies have long since industrialized, are atypical. In these regions, urbanization occurred long ago, and rural and suburban lifestyles cause higher emissions than urban ones, because they usually involve larger homes and more driving.

In the developing world, the alternative to urban living is often subsistence farming. So city-dwellers have higher emissions per capita because they are wealthier, with greater access to electricity and the conveniences it brings. In Africa, Asia, and Latin America, cities represent a growing share of population, economic activity, and emissions. (It’s worth noting, though, that while cities in developing countries have higher emissions than neighboring rural areas, they have lower emissions per dollar of GDP, and also urbanization tends to correspond with declining birth rates.) While most C40 cities are in developed countries, the group is actively recruiting new members in the developing world, and growing mega-cities like Shenzhen, Mumbai, Mexico City, and Beijing have joined.

According to a report by C40 released on Tuesday, cities can dramatically reduce their emissions by adopting policies that are within their authority. C40 estimates that by 2030, cities could achieve 10 percent of the global emissions reductions needed to close the gap between our current trajectory and what we need to stay below 2 degrees Celsius in warming, and by 2050 that figure could increase to 15 percent.

This would be achieved through three action areas: green building codes, transportation, and waste management. By adopting the most rigorous building codes, cities could cut their building energy usage by 30 percent. (The savings would actually be higher for each new building, but many buildings are already built, so that would be the average.) Cities could dramatically reduce their transportation emissions through switching to electric public vehicles and buses and reducing driving itself through smart urban planning and expanded mass transit. And, because garbage creates methane when decomposing, cities can reduce their emissions by increasing recycling and putting methane-collection systems in landfills.

Mayors of C40 cities are already pursuing many of the policies recommended in the report. As Rio de Janeiro Mayor Eduardo Paes, the chair of C40, noted at a press conference in New York last week, more than half of C40 cities now have bus rapid transit lines. Rio has more than 150 miles of BRT lines, which Paes predicts will help to dramatically increase mass-transit use.

New York Mayor Bill de Blasio (D) announced last week that the city will commit to reducing its emissions 80 percent below 1990 levels by 2050 — the global target for keeping warming below 2 degrees C. To help achieve that, his administration rolled out a comprehensive plan to improve energy efficiency in buildings. Major components include retrofitting city facilities and housing projects and providing “green mortgages” for private building owners who want to do the same, installing solar panels on city-owned rooftops, and tightening city building codes for energy efficiency in new buildings.

Depending on how you look at it, C40 may overstate or understate the potential for cities to reduce emissions. The report measures what would happen if all cities adopt the ideal policies for climate mitigation. That’s not politically realistic. On the other hand, there are plenty of urban opportunities that the report does not even go into, like deploying rooftop solar arrays to generate clean energy and urban farms to sequester CO2.

The biggest methodological flaw in C40’s new report is that it uses the U.N.’s definition of cities as metropolitan areas, not distinguishing between inner cities and suburbs. In developed countries, the majority of people in many metro areas live in the suburbs. The mayor of Miami or Atlanta has no authority over those much larger surrounding areas. To achieve these policy changes throughout the “urban” population would thus require the participation not just of big-city mayors, but of thousands upon thousands of small suburban town and county governments. Often, these areas are more politically conservative than major cities. As a practical matter, they are virtually always more sprawling and therefore less hospitable to mass transit.

The main reason C40 used this definition is because there’s better data available about metro areas than about major cities alone. The group does make two points in its defense, though. Central cities control a disproportionate share of some emissions sources, like office buildings and mass transit hubs. Also, in the developing world it is more common for the entire metro area to be under one urban or regional government, and those are the fastest-growing urban areas.

It isn’t just the C40 cities that are stepping up to address climate change. According to another report C40 just released, a total of 228 city governments, representing 436 million people, have set targets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. If they meet these targets, they will cumulatively save 13 gigatons of CO2 equivalent by 2050 — more than twice what the U.S. emits in a year from energy-related sources.

On Tuesday, at the U.N. Climate Summit, U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon and Michael Bloomberg, formerly New York’s mayor and now the U.N. special envoy for cities and climate change, announced the formation of a Compact of Mayors to address climate change. It is backed by C40, Local Governments for Sustainability (ICLEI), and United Cities and Local Governments. Cities that join the compact will collect and share information on best practices — which sounds unexciting. But Rit Aggarwala, an advisor to Bloomberg, told Grist this will achieve three things: “bring order out of chaos so the world can appreciate what’s happening at the city level,” “induce competition,” and “model the good behavior that we want national governments” to adopt.

Some people might wonder whether cities achieving these reductions on their own could take needed pressure off national governments. But it has the potential to show nations that emissions can be reduced without economic pain. As Bloomberg said of next year’s climate negotiations in Paris, “Countries won’t agree to cuts they think they can’t reach. Many national leaders don’t realize how much cities can do to reduce emissions.” The Compact of Mayors and C40 will be a success, said Bloomberg, “if we can close the gap between the perception of what nations can accomplish and what they really can.”