Now that we have established that gentrification is a thing, at least for those impacted by it, it’s worth noting that there are good and bad sides to it, and that includes when neighborhoods get environmental makeovers.

Neighborhood improvements like upgraded sewage infrastructure, LEED-certified green buildings, and bike lanes are great, but, counterintuitively, they can freak out residents of under-resourced communities who fear that such projects might price them out. When that happens, you’ve got what Jennifer Wolch, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, calls “environmental gentrification.”

The National Environmental Justice Advisory Council (NEJAC), a committee of non-government, community-based stakeholders that helps steer EPA policies, examined this phenom in its 2006 report, “The Unintended Impacts of Redevelopment and Revitalization Efforts in Five Environmental Justice Communities.” A key passage from that report:

[F]rom the perspective of gentrified and otherwise displaced residents and small businesses, it appears that the revitalization of their cities is being built on the back of the very citizens who suffered, in-place, through the times of abandonment and disinvestment. While these citizens are anxious to see their neighborhoods revitalized, they want to be able to continue living in their neighborhoods and participate in that revitalization.

D.C. was one of the five environmental justice communities studied for the report, with a focus on Navy Yard, the southeastern neighborhood that sits along the Anacostia river. Today, nine years after that report, the Navy Yard has been almost completely transformed from its former less-than-welcoming conditions. Once saturated with the blighted brown-space of abandoned federal buildings, it’s now flush with greenspace, bike lanes, a gorgeous set of condos, apartments, and townhouses overlooking the river. You won’t find anyone of any race who would argue that Navy Yard is a worse off place than what it was before, but the process of getting to this point was messy, according to the NEJAC report:

While outreach activities and Navy leadership were noteworthy, these programs achieved lower than expected success rates. This dynamic was mostly due to the community being unprepared to leverage opportunities and the government’s inability to provide greater assistance due to bureaucratic atrophy and entrenchment among federal and local agencies, turf issues, and personalities. Additionally, local nonprofits lacked the necessary capacity to take advantage of the revitalization process.

Today, African Americans living in the mostly working-class and low-income neighborhood Anacostia neighborhood no doubt have Navy Yard, as well as super-gentrified D.C. communities like Columbia Heights, on their minds as they hear about new plans to restore the longtime, pollution-plagued Anacostia river. Many in the Anacostia community have wondered for years if new riverfront developments on their side will mean turning the neighborhood into an unaffordable, condo-palooza like the one staring them in the face right across the river.

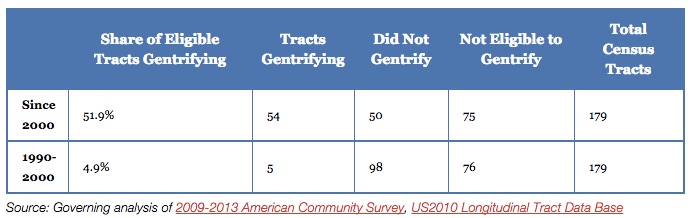

Those anxieties are understandable, considering that D.C. is one of the fastest gentrifying cities in the nation. According to Governing magazine’s analysis of 2009-2013 American Community Survey data and the US2010 Longitudinal Tract Data Base, less than 5 percent of D.C. neighborhoods that consisted of mostly low-income households were gentrified between 1990 and 2000. Since then, close to 52 percent of predominantly low-income neighborhoods have gentrified.

I discussed these residential anxieties with Doug Siglin, executive director of the Anacostia River Initiative, which has been helping lead river cleanup initiatives. His focus is not only on the river, but also the 1,200-plus acres of land along its east bank that belongs to the federal government, but sits empty, except for a bunch of weeds and wild trees. On gentrification, Siglin said simply, “It’s happening.”

The bigger question, said Siglin, is its pace — will it be overwhelming or gradual? Another question he wrestles with: “What does improving that area, and what does improving the pollution of the river really have to do with the dynamic of people beginning to move across the river and how the communities [starts] changing?”

To make sure that community members truly do have ownership and leadership in the planning, Siglin has partnered with people like Dennis Chestnut of Anacostia Groundwork, which has been organizing around this since 2007. “What we’d like to be able to do is help to sequence and control that movement so it isn’t overwhelming to the people who live there,” said Siglin.

He’s also allied with former D.C. mayor Anthony Williams, who heads Federal City Council, a nonprofit that’s been at the forefront of D.C. improvement initiatives since 1954. Williams’ administration is credited (or blamed, depending on who you talk to) with spurring the massive revitalization and gentrification seen throughout D.C. over the past decade. The question on many people’s minds is what’s in store for Anacostia once the river is improved?

“The original idea was to focus on an idea that would bring the city together, across racial and ethnic, income and even regional lines,” said Williams when I spoke to him in December about the Anacostia initiative. “A project that would embrace the environment is key to the future of the city, right? And the Anacostia is one of the most polluted rivers, if not the most polluted river in the country, and it’s within blocks of the capitol. So it’s important to address the environment … and, to use a hackneyed term, be sustainable”

Focusing on improving environmental issues helps communities with everything from public health to education and economics, said Williams, and so he sees the project as “the answer to pretty much every question.”

D.C. has used environmental restoration to answer questions like these before, though. In the early 1920s, Congress appropriated hundreds of thousands of dollars to cleanse areas along the Potomac River and the Tidal Basin (near where the national monuments stand today) to create beaches and parks for tourists and residents. In Andrew Kahrl’s book The Land Was Ours, he writes that the newly designed waterfront was produced with an “emphasis on unified, orderly urban spaces conducive to a healthy social order, and its faith in the ability to enhance public health, and thereby reshape society, through improving the environmental conditions of the city.”

But the district did not consider African Americans in those plans. Clarence O. Sherrill, appointed by President Warren G. Harding as the superintendent of public buildings and grounds in 1921, set policies to ensure that black residents would not enjoy these new waterfront amenities. Instead, they were granted access to beaches and parts of the river that were heavily polluted.

“This … was the direct result of improvements made to urban shorelines for the benefit of others,” wrote Kahrl.

Such intentional racial exclusion may no longer exist today, but the discriminatory outcomes of urban improvement persist in D.C. NEJAC’s 2006 report tells how “EPA may have unintentionally exacerbated historical gentrification and displacement,” through its brownfield remediation and watershed cleanup efforts. This has been true of both the public and private sectors.

It may explain, in part, why companies and nonprofits hoping to implant new environmentally friendly goods and services in neighborhoods of color are often met with suspicion. I started a series last year about how solar companies have been meeting resistance from some African American organizations and elected officials. As reported today in the L.A. Times, solar companies are baffled that anyone wouldn’t want all this sunny, delightful electricity they want to bring to poor, black neighborhoods. It’s not that black communities don’t want it, but rather that they’re painfully aware of the price tag — not what it might cost them in bills, but what it has cost them historically.

Anyone looking to correct that history should read the NEJAC report, which provides six recommendations for how to prevent outcomes like what happened with the Navy Yard. Among them are making sure “all stakeholders should have the opportunity for meaningful involvement in redevelopment and revitalization projects,” and encouraging “an initial neighborhood demographic assessment and a projected impact assessment regarding displacement at the earliest possible time in a redevelopment or revitalization project.”

The EPA, which was the target of the report, responded kindly to the recommendations, calling them “valuable and insightful.” The agency pledged to take stronger leadership and oversight in coordinating public outreach efforts, and made community involvement a requirement in ranking criteria for brownfield cleanup grant applications. The agency also said it would consider initiating demographic analyses “where and when appropriate” in efforts to curtail displacement. EPA’s correspondent on this was the Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response, an office that environmental justice advocates often credit with producing adequate models for equity analyses.

Measures like these have also been adopted by proponents of “equitable development,” a growth model pushed lately by urban planners who say that it can usher in neighborhood improvement without displacing longtime residents. The private sector might do well to follow the same playbook.

In my next piece, I’ll highlight a few projects where developers are attempting to do exactly that.

Correction: I originally wrote that less than 5 percent of all D.C. neighborhoods gentrified between 1990-2000 and about 52 percent of all neighborhoods gentrified after 2000. That was inaccurate. Those percentages were actually tied to those neighborhoods that were eligible for gentrification, meaning they were predominantly low-income. I regret the error.