No matter what desperate steps the Chinese government takes — banning coal-burning plants within the city limits, shuttering more than 300 factories, wiping out old vehicles and boilers, forcing heavy trucking to go nocturnal — this just keeps happening: Beijing’s smog has yet again soared off the charts.

On Thursday local time, Beijing measured “beyond index” levels of the dangerous airborne particulate matter known as PM2.5 — considered hazardous to human health because the tiny particles can embed deep in a person’s respiratory system. Those sky-high levels have been measured several times since the U.S. began measuring the city’s air using a device installed atop its embassy in Beijing in 2008, most notably during a “crazy bad” incident in 2010, and 2013’s “airpocalypse.”

Thursday’s levels indicated the concentration of PM2.5 exceeded 500 on an “Air Quality Index” (AQI) measured from the embassy. The Beijing municipal government maintains its own index, always notably lower than the U.S. readings, which reported an AQI of 430 — still hazardous. (Anything above 150 is considered unhealthy for the general population). Thursday’s levels are generally regarded as more than 20 times the limit recommended by the World Health Organization.

There you have it. We are now "Beyond Index" in terms of Beijing air pollution pic.twitter.com/lJgQR5X7hR

— Peter Schloss (@peterschloss) January 15, 2015

Another sunny day in #Beijing. #AQI over 600, i.e., "beyond index". Well beyond. pic.twitter.com/fCb04H9rvY

— Nicholas P Manganaro (@NicholasXPM) January 15, 2015

Air in Beijing is "beyond index." Off the charts & beyond hazardous. CCTV Tower invisible from NYT office. pic.twitter.com/8fpDahRE1E

— Edward Wong (@ewong) January 15, 2015

Beijing pollution off the charts today pic.twitter.com/ng3TLe3MSi

— ian bremmer (@ianbremmer) January 15, 2015

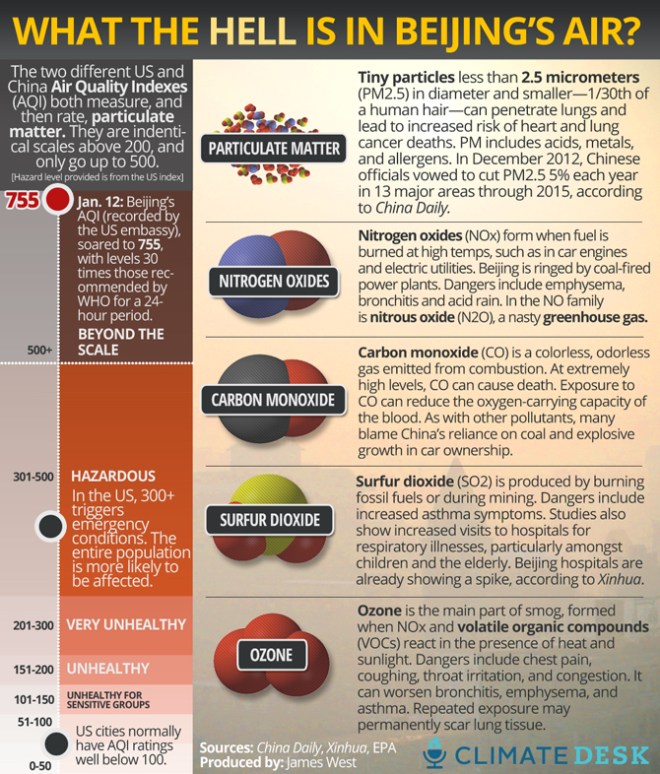

Despite the frigid mass of putrid air, this week’s levels don’t come close to records set in 2013, when the AQI surged to over 755. Then, expats gave it a nickname: “airpocalypse.” It covered 1 million square miles (2.7 million square kilometers) of the country with a pall of smog that impacted more than 600 million people. I made this chart then to show what exactly was in Beijing’s air, a lethal combination of particulate matter, nitrogen oxides, sulfur dioxide, carbon monoxide, and ozone. It also gives you a sense of how the Air Quality Index works:

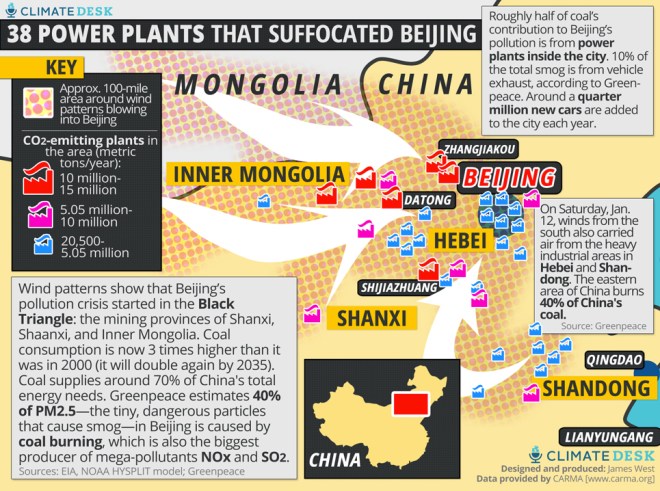

One reason it’s so hard to control the air quality in Beijing is that the smog problem sweeps in from neighboring provinces, known as the “black triangle” — Shanxi, Shaanxi, and Inner Mongolia. Prevailing wind patterns in that area of China pick up the pollution from at least 38 coal-fired power plants and send it straight into Beijing, which is landlocked and tends to trap the smog.

As I’ve reported previously, the smog is the main thing driving so much of China’s push to tackle climate change (reducing CO2 emissions will also cut pollution) and its exploration of natural gas through a major fracking push in the southwestern province of Sichuan. It’s worth noting that China continues to be the world’s biggest investor in clean energy technologies.

But so long as smog continues to blanket cities like Beijing, home to 21 million people, the government will continue to face mounting political pressure amongst an uneasy population that was promised, along with economic prosperity and greater freedoms associated with opening up to the rest of the world, a better quality of life.

This story was produced as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

This story was produced as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.