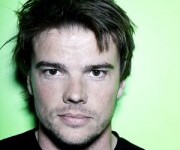

Bjarke Ingels.This interview originally appeared in The Dirt.

Bjarke Ingels is founding partner of Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG). Ingels, rated as one of the 100 most creative people in business by Fast Company, is also a visiting professor at Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

Q. You’ve been calling for a new approach, “hedonistic sustainability,” which is “sustainability that improves the quality of life and human enjoyment.” Why is it important for sustainability to enhance pleasure?

A. The whole discussion about sustainability isn’t popular because it’s always presented as a downgrade. The position has been, there’s a limit to how good a time we can have. We have to downgrade our current lifestyle to achieve something that is sustainable. That makes it essentially undesirable. People can be to the left [politically] and maybe shop a little bit green, but they’re not going to drop their car if they have to pick up their kids from football and go to the movies. It becomes an impossible mission.

However, there’s nothing in our lifestyle that necessarily requires CO2 emissions. It’s just an unforeseen side effect of all of the increases in quality of life that we have been able to deliver through modernization and industrialization. As we get smarter and more aware of these side effects, we can factor them in and start delivering urban mobility without emissions by switching to fuel cells or batteries.

My two favorite examples from Copenhagen: 37 percent of the Copenhageners today commute by bicycle so they are never stuck in a traffic jam. You know how unenjoyable it is to sit stuck in traffic, especially if you do it every day. So 37 percent of the Copenhageners never experience that because they have the convenience of going from A to B on a bicycle. Also, our port has become so clean you can swim in it. You don’t have to commute to the Hamptons to have clean water. You can actually jump in the port downtown. So these are basic examples where sustainability actually starts becoming an upgrade rather than a downgrade.

Q. In your large-scale master plan and park projects, you often feature landscape loops. For example, in your Stockholmsporten project, “a continuous bike and pedestrian path reconnects different areas in an un-hierarchical and democratic way.” In Clover Block, there’s a perimeter loop surrounding a massive lawn. In another project still in the idea phase, you propose a loop city in the Copenhagen suburbs. What’s the attraction to these loop forms? How well do they work?

Ingels’ proposed loop city for Copenhagen.A. They have to do with connectivity. You can see it in the loop city idea. The old paradigm for Copenhagen was the five finger plan, where from the central orientation of downtown Copenhagen you have these corridors of urban tissue that extend, leaving gaps between the fingers [for] green and agriculture. But, of course, this is a hierarchical and central model where the further you get out in the finger, the further you are away from the concentration of connectivity and activity.

Given a lot of the Copenhageners live out in the fingers, and a lot of people actually work in this finger and live in this finger and play football in this finger, another kind of connectivity starts becoming interesting … So what we are proposing with the loop city is to create a … continuous urban tissue where people are no longer condemned to live in the outskirts and commuting into downtown Copenhagen and back out again. There will be a continuous ability to interact between these kind of urban areas that now house the majority of the population of the area. You have 500,000 people living in the Copenhagen inner city and you have 3.5 million people in the region.

Q. You are well-known for integrating building and landscape in your large-scale residential projects. In The Mountain, terraced apartments are arranged so each gets sunlight and has its own individual garden. Other projects, including your upcoming West 57th Street residential complex in New York City, Vilhelmsro School, and the 8HOUSE project in Copenhagen, combine building and landscape in the form of green roofs. What comes first: the building or landscape? How do they mesh?

The 8HOUSE project.A. As you mentioned, it is often hard to distinguish where one discipline begins and another one ends. We’ve had lots of collaborations with landscape architects. It’s an interplay.

In the case of the 8HOUSE, we wanted to include the typology of the townhouse with the small garden and all of the social interaction that happens when people have a little piece of their private life happening in the semi-open, like the porch in an American suburban setting. Sitting out on the porch, you can holler at the neighbors and see who’s home and who’s not. You’re at home and sort of semi-private but people can actually access you and there’s the possibility of spontaneous interaction. We simply tried to introduce that social typology found in a dense urban block by simply allowing it to invade the three-dimensional space of the open block. To really make it townhouses with gardens, we wanted to make sure that there were trees and plants. To recreate the social possibilities, we had to include the element of landscape.

In the West 57th project, the entire architecture is created as the framework for the courtyard. Somebody called it a Bonsai Central Park. It’s probably one-five-hundredth the size of Central Park, but by insisting on creating an urban oasis for the residents, the whole volume of the block, the whole architecture, was dramatically reconfigured, and we can no longer rely on the traditional boxy typology. We created this highly asymmetrical roofscape that allows in daylight and creates views into a sort of oasis. It was really the Central Park of the Copenhagen courtyard. We arrived at a completely different architecture because of Central Park.

Q. In Copenhagen, you are designing a 100-meter-tall waste-to-energy plant that will double as a ski slope and civic center. What did Copenhagen figure out that other cities haven’t? Why aren’t more cities designing and building imaginative public works projects that solve multiple problems at once?

The waste-to-energy plant that doubles as a ski slope and civic center.A. We are quite interested in this new genre of projects that we call social infrastructure. A major part of any city’s annual construction budget goes into improving highly utilitarian structures that are purely in the domain of civil engineering. The holistic, integral thinking that architecture and landscape architecture can contribute, where it’s not technology-driven but actually human-centered, can be transformative. Instead of getting your nasty highway overpasses that create shaded areas for dodgy activities, you start incorporating social attributes and making sure that when a necessary piece of infrastructure like a train connection, a bus line, a roadway, a power cable, is carried through, that it’s done in such a way that it actually increases connectivity and creates new activities, so that the sheltered spaces become sort of sports facilities or market halls.

There are tons of examples where decommissioned infrastructure turns into new programs. In Paris, Berlin, or London, you have galleries and marketplaces occupying the archways under the train lines. You have the High Line in New York. You have tons of examples where, after the fact, we can re-imagine the infrastructure. But what if we, from day one, can actually turn the power plant into a public park?

The power plant has a budget of $700 million USD, so the configuration of the roofscape is nothing compared to the overall budget. As a result, people don’t feel that we’re dumping a big boxy factory that blocks their views and casts shadows into their neighborhood. They feel that we’re actually creating a public amenity. Normally we would get not-in-my-back-yard letters and complaints about the project. Now, we’re actually getting letters from people asking when it’s going to open. So it’s also a way of integrating the necessary infrastructure into our urban fabric rather than sort of putting it in some kind of industrial wasteland in the periphery of our city.

Q. I saw you discussing your buildings in the context of parkour in the film My Playground. Do you think through how your buildings and spaces could be reappropriated?

A. The driving force of our design is to saturate it with possibility. We like the whole notion of parkour. What architects do is put potential out there, and what parkour people do is to expand the preconceived or pre-planned possible use and take it one step further, essentially to expand the human realm of the city. That said, take a project like the 8HOUSE, where we made this mountain path that allows people to walk and bicycle all the way to the 10th floor. Sociological studies from the ’70s indicate that children living higher than the third floor rarely come down and play because of the disconnect, whereas here, if you were living on the 10th floor, you could actually just walk four houses down and play with your neighbor to create this spontaneous social interaction. That’s also why the 8HOUSE is actually a loop. Everybody’s connected to everybody.

Because Copenhagen is completely flat, there is no landscape, there is no vista where you can go and enjoy the view and hold your girlfriend’s hand, blah, blah, and enjoy the beautiful scene except now, at 8HOUSE, there actually is. So what we didn’t imagine is people from around Copenhagen actually go to 8HOUSE on weekends for a walk because this is the only place you can actually enjoy the view of the city and get this sort of three-dimensional experience that you get in a lot of other cities naturally.