Photo:Randal FordThe house was a nightmare. “It had been collecting dust and graffiti since Katrina and there was something very shabby and Brothers Grimm about it,” says Candy Chang, an artist and graphic designer who lives just a few blocks from the place in New Orleans.

Photo:Randal FordThe house was a nightmare. “It had been collecting dust and graffiti since Katrina and there was something very shabby and Brothers Grimm about it,” says Candy Chang, an artist and graphic designer who lives just a few blocks from the place in New Orleans.

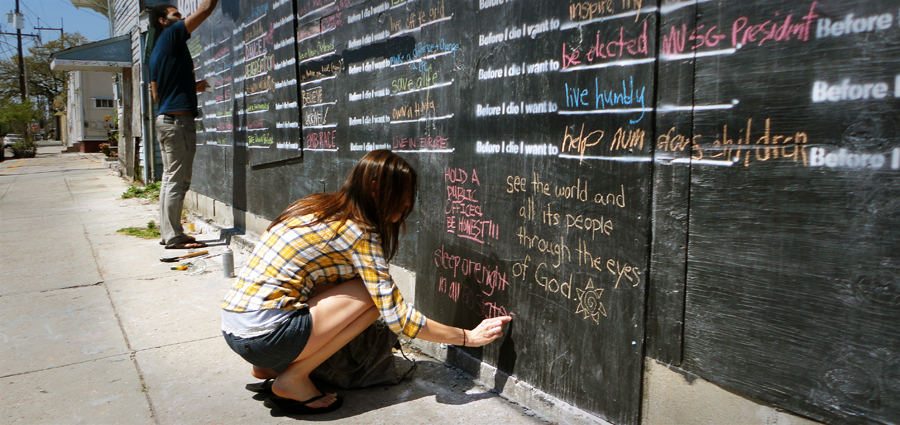

But where others saw blight, Chang saw an opportunity, and armed with a few buckets of paint, she transformed the derelict house from a symbol of the community’s decay into an emblem of its collective aspirations.

With permission from the property owner and neighborhood groups, Chang turned the front wall of the house into a giant chalkboard, stenciling, “Before I die I want to ___________” across the boarded-up facade dozens of times. The statement became an open invitation to residents to fill in the blank. And they did.

“Before I die I want to finish school.”

“Before I die I want to write a book.”

“Before I die I want to be completely myself.”

“Before I die I want to see all homeless people with homes.”

“Before I die I want to feel like the only girl in the room.”

“Before I die I want to sing for millions.”

Photo: c/o Candy Chang

Photo: c/o Candy Chang

The list went on and on. Chang was floored.

Why did it touch such a nerve? “It’s about knowing you’re not alone,” Chang writes in an email. “It’s about understanding your neighbors in a new and enlightening way.”

That, in a nutshell, is the magic behind Chang’s work, which she calls “a kind of love child of urban planning and street art.” Over the past couple of years, Chang’s gift for drawing the stories out of urban neighborhoods has won her accolades and commissions around the world. And she has done most of it with simple, inexpensive tools like chalk, stickers, and spray paint.

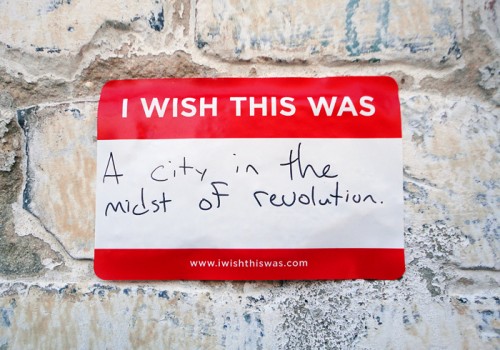

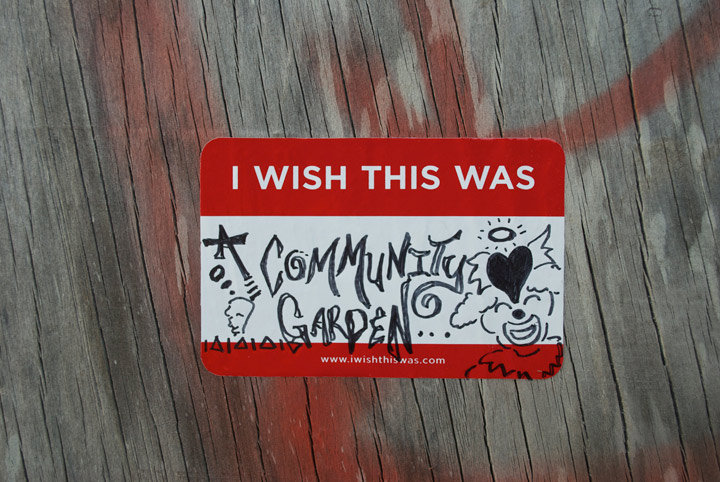

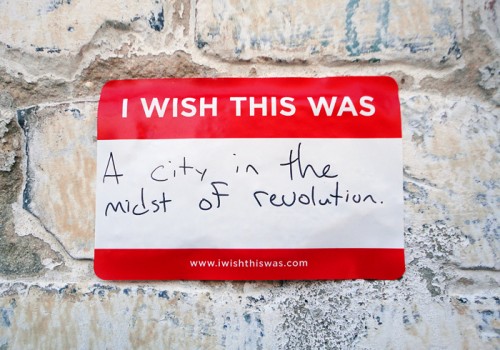

In the fall of 2010, Chang began putting fill-in-the-blank stickers on abandoned storefronts in New Orleans reading, “I wish this was.” Residents took it from there:

“I wish this was a grocery with fresh produce and pumpkin pie.”

“I wish this was a row of trees.”

“I wish this was a laundrymat.”

“I wish this was a hammock on a beach.”

“I wish this was a higher priority of the city.”

“I wish this was not my neighbor.”

Photo: c/o Candy Chang“One of my favorites is a sticker where someone wrote, ‘I wish this was a bakery’ and someone else wrote underneath, ‘if you can get the financing, i will do the baking!'” Chang says. “And that leads to the bigger question: What if residents had better tools to self-organize and shape the development of their neighborhoods? What if we could prove there was a strong enough customer base for a new business to open? What if we could better connect residents who want certain things with like-minded people and initiatives?”

Photo: c/o Candy Chang“One of my favorites is a sticker where someone wrote, ‘I wish this was a bakery’ and someone else wrote underneath, ‘if you can get the financing, i will do the baking!'” Chang says. “And that leads to the bigger question: What if residents had better tools to self-organize and shape the development of their neighborhoods? What if we could prove there was a strong enough customer base for a new business to open? What if we could better connect residents who want certain things with like-minded people and initiatives?”

With that in mind, Chang has teamed up with several others to launch Neighborland, a project that combines some of her analog tools with an online platform where people can voice their opinions, share local knowledge, and discuss what they need in their neighborhoods. Working with an urban innovation fellowship from Tulane University and support from the Rockefeller Foundation, she and her colleagues launched a basic website for New Orleans this fall.

Chang says that community organizations are using the tool to gather ideas for two major commercial corridors in the city, and an architect/developer is collecting ideas for the commercial ground floor of a downtown high-rise. “The idea is to make our neighborhoods more reflective of our needs,” she says. “Who knows a neighborhood better than the people who live and work there?”

Chang traces the inspiration for her work to the storefronts and lampposts in New York City’s Chinatown, where she lived before moving to New Orleans. These surfaces were covered in posters, flyers, and stickers — a tattered mosaic of local happenings, offerings, and announcements. Just a few blocks away was 11 Spring Street, a center of the city’s street art scene.

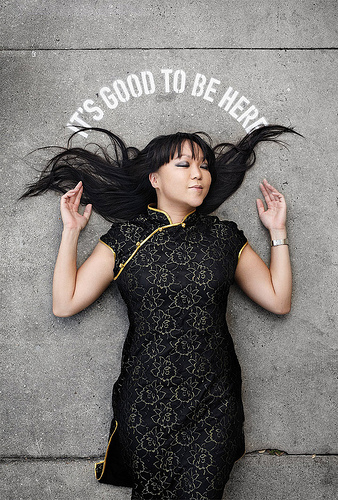

Photo: c/o Candy Chang“Being surrounded by these blocks made me feel like public space wasn’t a pristine, sacred space that I shouldn’t touch,” Chang says. “Instead, it made me feel like it was an informal, colorful place where I could add to the mix too.”

Photo: c/o Candy Chang“Being surrounded by these blocks made me feel like public space wasn’t a pristine, sacred space that I shouldn’t touch,” Chang says. “Instead, it made me feel like it was an informal, colorful place where I could add to the mix too.”

Some friends of Chang’s ran an indie record label, and they started putting up stickers and posters around town. She was working at the New York Times at the time, and she started slapping moustache stickers on the faces in ads on the subway trains on her way to work.

It was at about that time that Chang first heard the story of Jane Jacobs, a New York housewife-turned-activist who led the fight against a plan spearheaded by “master builder” Robert Moses that would have leveled entire neighborhoods to make way for a new highway.

“The ‘slums’ Moses tried to clear out are now some of the greatest neighborhoods in New York: the West Village, Soho, Chinatown, the East Village, and the Lower East Side,” Chang says. “It made me think about all the cities that could have been, and the cities that are now, depending on who gets involved.”

The story inspired her to study urban planning at Columbia University — and landed her at this unique intersection of street art, social activism, and urban planning.

Photo: c/o Candy ChangWhile Chang is experimenting with digital media, it’s the low-tech, street-level work that may have the most potential for drawing out voices that would not otherwise be heard. “Where better to reach out to all your neighbors than in the very public spaces we share every day?” Chang asks. “If spaces were designed differently and we were given the opportunity, could we learn more from each other? Could we self-organize and become more effective agents in our communities?”

Photo: c/o Candy ChangWhile Chang is experimenting with digital media, it’s the low-tech, street-level work that may have the most potential for drawing out voices that would not otherwise be heard. “Where better to reach out to all your neighbors than in the very public spaces we share every day?” Chang asks. “If spaces were designed differently and we were given the opportunity, could we learn more from each other? Could we self-organize and become more effective agents in our communities?”

It’s an intriguing question — and too early in Chang’s experiment to answer. But she has proven one thing already: The city is full of stories, if we can just find a way to listen.