First in a series on lessons from California’s water crisis.

When George McFadden sits at his computer to analyze crop photos, he looks like a doctor pointing out trouble spots on an X-ray. He identifies unnatural lines, “blob-like” patterns, and streaks clouding a field. All can indicate a troubling diagnosis.

“Can you see these little dots?” McFadden asks, pointing at a thermal shot of a tomato field that has suffered from a defective irrigation system. The dots on the image revealed that the system’s drip line had tears in it, he says. Watering the field became “like taking a straw, putting a bunch of pinholes in it, and trying to pump water through it.” The tomato grower used the image to show the manufacturer that the irrigation line was defective.

“Pretty striking,” McFadden says, still examining the screen. The 32-year-old field agronomist works for Ceres Imaging, a start-up in Oakland, California, that uses aerial imagery to help farmers optimize water and fertilizer application. The company is part of a growing contingent of technology start-ups vying to transform one of the state’s most powerful industries — agriculture — for a future in which its most important input grows increasingly scarce, and every drop counts.

California is the country’s top agricultural producer, growing two-thirds of the nation’s fruits and nuts and more than a third of its vegetables. Golden State farms and ranches constitute a $54 billion annual industry. The state’s ag-focused economy means growers have historically been power players in politics, especially in discussions about apportioning water.

But as growth, drought, and climate change have increased scarcity and led to louder calls for conservation, the industry’s clout has been waning.

In 2015, during a record-setting drought, Gov. Jerry Brown ordered cities and towns to reduce water use by 25 percent — the first such mandatory cutback in state history. It prompted some to criticize the agriculture sector’s consumption — which makes up 80 percent of state use — and question why the industry was spared.

Brown defended the decision, saying farmers were already among those hardest hit. Many faced huge cuts to water allotments from state and federal systems and had to pay overblown sums for the water they could access. This was particularly hard on farmers because they operate with narrow profit margins, and more than 80 percent of California farms are small and family-owned. A few months after the order for cities, as the drought slid into its fourth year, some farmers were slammed with further restrictions.

A study released last summer estimated that the drought would cost California’s agricultural industry more than $600 million in 2016. For 2015, the estimate was $2.7 billion.

And though much of the state has gotten drenched this winter — over 70 percent of California is now out of drought — the long-term forecast for severe water shortages remains unchanged. In April, Brown ended the state of emergency for most parts of California; it had been in effect since January 2014. But climate change will continue tightening the state’s water supply. To keep crop yields high, or even just to stay in business, farmers will have to become more calculating.

That’s where technology comes in.

Silicon Valley, the nation’s most powerful tech hub, sits in the middle of California’s most productive farmland. To the east lies the Central Valley, growing crops like almonds and walnuts; to the north is Napa Valley, with its world-famous grapes; and to the south is the Central Coast, the “salad bowl of the world.”

Despite their proximity, the agriculture and technology sectors haven’t had much interaction. Though both are powerful forces in the state — ag a long-time influencer, tech a newer one — the cultural divide between the two is vast.

But bridging that gap could help solve one of agriculture’s most pernicious problems: water scarcity. Technologists are betting their solutions will ensure a steady stream of revenue for both industries in an increasingly dry world.

Jenna Rodriguez, Ceres’ product manager, was raised in Linden, California, a small agricultural town on the northern tip of the San Joaquin Valley in the center of the state.

“I’ve grown up listening to growers talk about the water situation,” Rodriguez tells me. “They’re growing food to also feed their families. And when a family farm has water allocations cut back to zero percent, it can make or break the income for a family.”

After spending summers driving tractors and bailers at her parents’ hay harvesting business, Rodriguez got a Ph.D. in hydrological sciences. Now she’s based in the Central Valley town of Ripon, working to bring Ceres’ technology to more farmers throughout the area.

The day we spoke, Rodriguez had just finalized plans for Ceres’ launch into Hawaii, where its imaging system will be used on tropical crops like pineapple and coffee as well as commodities like corn and soybeans. When it launched in 2014, Ceres initially focused on lucrative nut crops in the Central Valley. Then it expanded to other crops in California, the Midwest, and even Australia. In total, the company now analyzes hundreds of thousands of acres for its clients.

Some of Ceres’ aerial technology is similar to what has been used by other imaging companies for decades. But Ceres’ chlorophyll measurements are a proprietary product. Its image processing and the guidance it offers to growers are also unique.

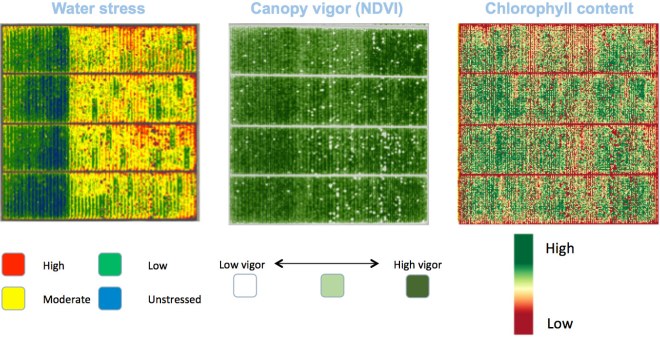

To assess fields, Ceres hires pilots who fly their aircraft low over the ground. The company attaches special cameras focused on particular wavelengths to assess water stress, chlorophyll content, and biomass — all indicators of health in a crop. Within 24 to 48 hours, growers can access processed imagery on devices like phones or tablets, which McFadden says are popular with growers in the field.

Then someone on Ceres’ small staff of 24, often Rodriguez or McFadden, will work with growers to explain the significance of the patterns and colors expressed in the images. Blue and green indicate healthy plants, while red and yellow show water stress and potential irrigation problems.

Ceres images from a 160-acre almond study. (Ceres Imaging)

“It’s like this constant battle of maintaining and operating your irrigation system,” says McFadden, sitting at a gray folding table in Ceres’ bare-bones office. “A big thing with tomatoes is identifying the leaks. Currently [growers] have teams of people who will go and walk each row of the tomato field, which is a pretty inefficient use of time.”

According to independent field tests, the imagery works. Since 2014, Ceres has teamed up with the University of California Cooperative Extension, a program that has provided agricultural data to growers in California for over a century. The extension has worked on several studies with Ceres, including a trial for the Almond Board of California that measured the response of nuts to different rates of watering.

In that study, data from Ceres images matched well with the extension’s ground measurements, says Blake Sanden, who headed up the trial. He’s an irrigation and soils management adviser for the extension program — or, as he calls himself, in a voice as slow as molasses, “the water and mud guy for Kern County,” which sits at the southern end of the San Joaquin Valley.

Ceres’ relationship with the extension program has helped the company gain trust with sometimes-skeptical farmers. Sanden says the extension’s government-funded trials are “the gold standard of efficacy” for new products in the ag market.

Agronomist George McFadden uses aerial imagery to help farmers save water. (Emma Foehringer Merchant)

Even with that kind of validation, though, it takes effort to convince growers that a new product isn’t snake oil. Farmers tend to be skeptical of change and hesitant to acknowledge that they’ll need to cede more water to other uses in the state.

Sanden told me the Central Valley’s attitude toward a water-stressed future can be summed up in two words: “Fear and trepidation.”

Farmers, who Rodriguez calls “the original stewards of the environment,” are not prone to waste. But in the past, many California growers had cheap, consistent access to water distributed by systems like the Central Valley Project, a federal network of reservoirs and irrigation channels. More recently, though, programs developed to keep growers flush have dried up or apportioned some of them much less water than in the past — down to nothing.

“The attitude used to be, ‘I can find water,’” says Sanden. “I would say that 30, 40 years ago there was an attitude of hope, overconfidence — whatever you want to call it — that some of the restrictions on pumping water [would] go away.” He says growers expected decision-makers “to come back to reality and understand that we’ve got to make money in California and grow food.”

But the restrictions didn’t go away. Instead, they became stricter. Those constraints, along with the drought, have threatened grower livelihoods across the state. The uncertainty has made farmers friendlier to new technologies. For many, it’s been the only way to survive.

Dave Santos, who grows apricots, cherries, and almonds in Patterson, a Central Valley town sandwiched between I-5 and the San Joaquin River, remembers the advent of drip irrigation, which his 900-acre farm has used for more than 30 years. Since then, he says, a lot more innovation has sprung up — so much so that 67-year-old Santos leaves some of it to his son, like experimenting with aerial imaging.

“I’m just a neophyte in all of this stuff,” he says. “We’re trying to do our best.”

Today, growers like Santos and his son attend conferences to learn about the latest tools and meet with a rotating cast of salespeople who pitch them on new products and services.

“Obviously, with the California drought, anything that can help with water efficiency, they’re willing to spend time and listen to see what’s available,” McFadden says. “In general, all these costs are increasing, but the revenue is not. So how do they deal with that? Become more efficient.”

Scott Bryan and Tom Ferguson meet me in a French café in San Francisco’s Financial District. Next door is a hip ice cream shop, and above that is their tiny office — in a coworking space — from which they run the only California-based start-up accelerator focused specifically on water innovation.

Each year, Imagine H2O handpicks about 10 start-ups working on “solving” water. Competition is fierce. The nonprofit’s staff of four and a group of judges comb through about 100 applications for each cycle. They’re looking for a special sauce that includes commercial potential, interesting technology, and solutions that keep the customer in mind.

“There are a lot of people in water who just have an idea,” says Bryan, the group’s president. “It can be something on the side.”

“Let’s tow icebergs down from Alaska — which is a thing,” offers Ferguson.

“Which is a thing,” Bryan says.

“Apparently,” Ferguson adds wryly.

The day we sit down together in January, they’d just begun working with the 12 companies selected for the 2017 program. Over the course of nearly a year, the selected companies will work with industry mentors, hone their pitches, and liaise with potential customers, partners, and investors. Imagine H2O’s goal is to get start-ups from point A to whatever a company envisions as point B. Since 2009, the program has helped 650 companies that are working on water scarcity and conservation in more than 30 countries.

In March, Imagine H2O held a swanky champagne reception for its new cohort at a San Francisco event space bathed in blue light. While suited attendees milled around the room, the cohort’s entrepreneurs floated next to display tables, ready to pitch their technologies.

Last year, Ceres was among Imagine H2O’s chosen cohort. At the 2016 reception, the company was selected from the larger group as the program’s Water Data Challenge winner.

“They had clearly spent a hell of a lot of time with their customers,” says Ferguson, the vice president of programming. “Your network is crucial.” Farmers want to know: “What’s my neighbor doing? Does he trust it?” he says.

“It’s the relationship component,” adds Bryan.

“Totally,” Ferguson agrees. “That’s kind of the determinant of virality — to use a terrible San Francisco phrase.”

What many tech entrepreneurs get wrong, according to the two, is assuming growers have an unlimited capacity to adopt new technology. “Is a farmer going to have 10 different phones with 40 different apps on each phone?” Bryan asks. “No. The farmer is going to be like anyone else — they’re going to use technology, but they’re going to use the stuff that has some kind of return for them.”

Rodriguez says there’s still “a substantial barrier in general between ag tech and agriculture.” But people working at the intersection insist both sides have the desire to find technological solutions that address the water crisis.

“The agricultural industry wants to be more productive, they want to make money, they want to be profitable,” says Graeme Jarvis, an Imagine H2O accelerator judge and mentor, who has worked in start-ups and who helped build John Deere’s precision agriculture business unit.

“It just so happens that by leveraging technology and new ways of understanding how to drive those in-field decisions,” Jarvis says, “[you] actually end up having this secondary or complementary benefit, which is better water stewardship. That said, it’s early days in the realization of a lot of this.”

To succeed, technologists will have to meet farmers in the field.

Bryan says, “The biggest mistake people make: They don’t understand what the on-the-ground needs and limitations are.” You can only grasp that by talking, and especially listening, to growers. “If you don’t, you’re just another entrepreneur with a gadget looking for a problem.”