This story was originally published by Wired and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Later this week, a single-seat, solar-powered plane with a wingspan longer than that of a Boeing 747 will take off from Nanjing, China, headed for Honolulu. For a normal passenger jet, that’s about a 12-hour flight. Solar Impulse 2, the 5,000-pound plane powered by nothing but sunshine, will take five days.

This is by far the hardest part of the plane’s journey around the world, which started in Abu Dhabi last month, and should finish there in August. Swiss pilots Bertrand Piccard and André Borschberg have been working up to this for 12 years, and they’re fully aware of how trying it will be.

“If we are optimistic, we will say that we’ve done six legs out of 12,” Piccard says. “And if we are pessimistic, we will say have have traveled 8,000 kilometers out of 35,000.”

Which is to say, things are going according to plan, but there’s much left to do, including the flight to Honolulu, then a 3,000-mile leap over the rest of the Pacific to Phoenix, Ariz.

The trick to staying aloft for days at a time is straightforward. The solar panels that cover the wings and fuselage of Solar Impulse 2 charge four extra-efficient batteries, which power the 17.4-horsepower motors. You charge up when the sun’s out and cruise at up to 28,000 feet. At night, you drop to about 5,000 feet, converting altitude into distance.

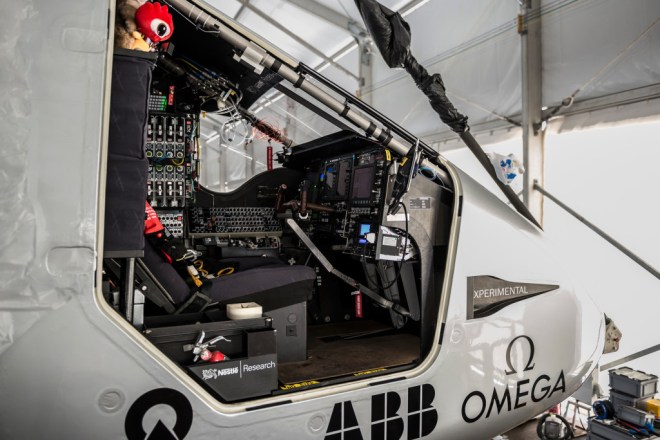

There are two factors that make the Pacific crossing especially challenging: The ocean’s size and the pokey speed of the plane (try 20 to 90 mph) mean each pilot will need to spend four or five days and nights aloft to reach land, in a cockpit that resembles a tube hotel in miniature. The second problem is the weather: Solar Impulse 2 needs pretty specific conditions to takeoff, cruise, and land — and that all needs to be planned out five days in advance.

Borschberg is scheduled to take off from Nanjin on May 7, at the earliest. If the flight goes as expected, he will take five days to make the trip to Honolulu. Then Piccard will make the four-day trip to Phoenix.

André Borschberg has spent 72 hours at a time in a simulator to prepare for this flight.Niels Ackermann/Rezo.ch/Solar Impulse

Pilot preparation

It doesn’t sound like much fun: There’s no walking around, or even standing up in, the 135-cubic foot cockpit. The cabin is neither heated nor pressurized, though it is insulated.

To get used to the cramped conditions, the pilots have spent long stretches in a simulator. They use meditation, breathing exercises, and whatever yoga they can manage to keep their bodies and minds feeling as fresh as possible.

Piccard and Borschberg will sleep in 20 minute stretches (the aircraft has autopilot functions and there’s not much to collide with over the Pacific), six to eight times a day. It’s hardly a good night’s rest, but it’s enough to get by, and the seat fully reclines. They have an alarm set to wake them up, but their bodies have gotten used to the routine, and don’t really need it, Piccard says. “It’s very interesting how the human mind can adapt to this type of new situation.”

The grub sounds pretty good, especially for air travel: Nestlé made special meals that can survive temperatures from -4 to 95 degrees Fahrenheit. There’s mushroom risotto, chicken with rice, and potatoes with cream and cheese. “It’s very nice,” Piccard says. The toilet, FYI, is built into the seat.

It may seem difficult to stay focused when you’ve seen nothing but ocean for days on end, but it’s not a major concern to the pilots. “There’s quite a lot of things to do,” Borschberg says. More importantly, they’ve been working up to this for more than a decade. They’re jazzed.

Of course, they’ve got to be ready for things to go wrong. In the event of a sudden catastrophe, like an engine or battery fire, they’ve trained for bailing. If cloudy weather stops the panels from charging the batteries adequately, Piccard and Borschberg will take their time putting on the dry suit, preparing the parachute, alerting mission control, and switching on an emergency beacon. “You get out very peacefully,” Piccard says.

The key in any situation is getting away from the plane — there’s a serious risk of electrocution when you fly a pile of electronics and batteries into the ocean. Then you settle into your life raft, because you’re thousands of miles from land, and major shipping lanes, it may take two or three days to be picked up.

The cockpit of Solar Impulse 2 resembles a tube hotel, in miniature. Solar Impulse/Pizzolante

The weather game

There’s a lot to take into account, says team meteorologist Luc Trullemans. Routes are decided using radar and satellite data, and flight simulations. Equipment from engineering consultancy Altran and a team mathematician lend a hand. Cloudy skies mean the solar panels can’t recharge the batteries. Wind conditions are crucial: Tailwinds are best, and the team will tolerate cross tailwinds up to 45 degrees (90 degrees would be blow fully sideways). Headwinds are a problem for a plane with limited power: Between Myanmar and Chongqing, China, Piccard found himself flying backwards at one point.

The six legs of the Solar Impulse 2 journey already completed have been relatively short affairs, between 15 and 20 hours. That’s not so tricky to plan, because at the time of takeoff, you have an excellent idea of what the weather will look like for the whole flight.

All that gets way more difficult now, because the team can’t predict the weather with the accuracy it wants more than three days in advance. “We must be 100 percent certain with our weather forecasts for the first three days of the flight and of course, the takeoff conditions,” says Trullemans. After that, the route can always be changed … on the fly … but major deviations are best avoided. The plan is to keep a sharp eye on coming conditions. The pilot can fly to the north or south to avoid a cold front, for example.

Beyond that, you hope for the best: Tailwinds, clear skies, and no need to inflate that life raft.