Should I learn to drive? I am 30 years old and have been OK with relying on public transport thus far. I have also been glad to not have to decide whether to drive and emit pollution every time I make a trip in my city — because I can’t even drive! I don’t mind leading a smaller, simpler, slower life, and I am proud of the lengths I have gone to avoid causing extra car trips — even lugging home items of furniture on the bus. But there are some things I’d like to do in the next few years that probably require being able to drive places, e.g., adopting a large dog and doing a bit of fieldwork for a Ph.D. in a climate mitigation area.

I assume I would expend 50 to 100 hours’ worth of emissions just to get a license. (The cars I see at driving schools seem to all be fossil fuel–combusting.) And then afterward, I would be more likely to drive, own a car, etc. What should I do? One idea I can think of already is to write to the driving school and ask them to get an electric vehicle fleet.

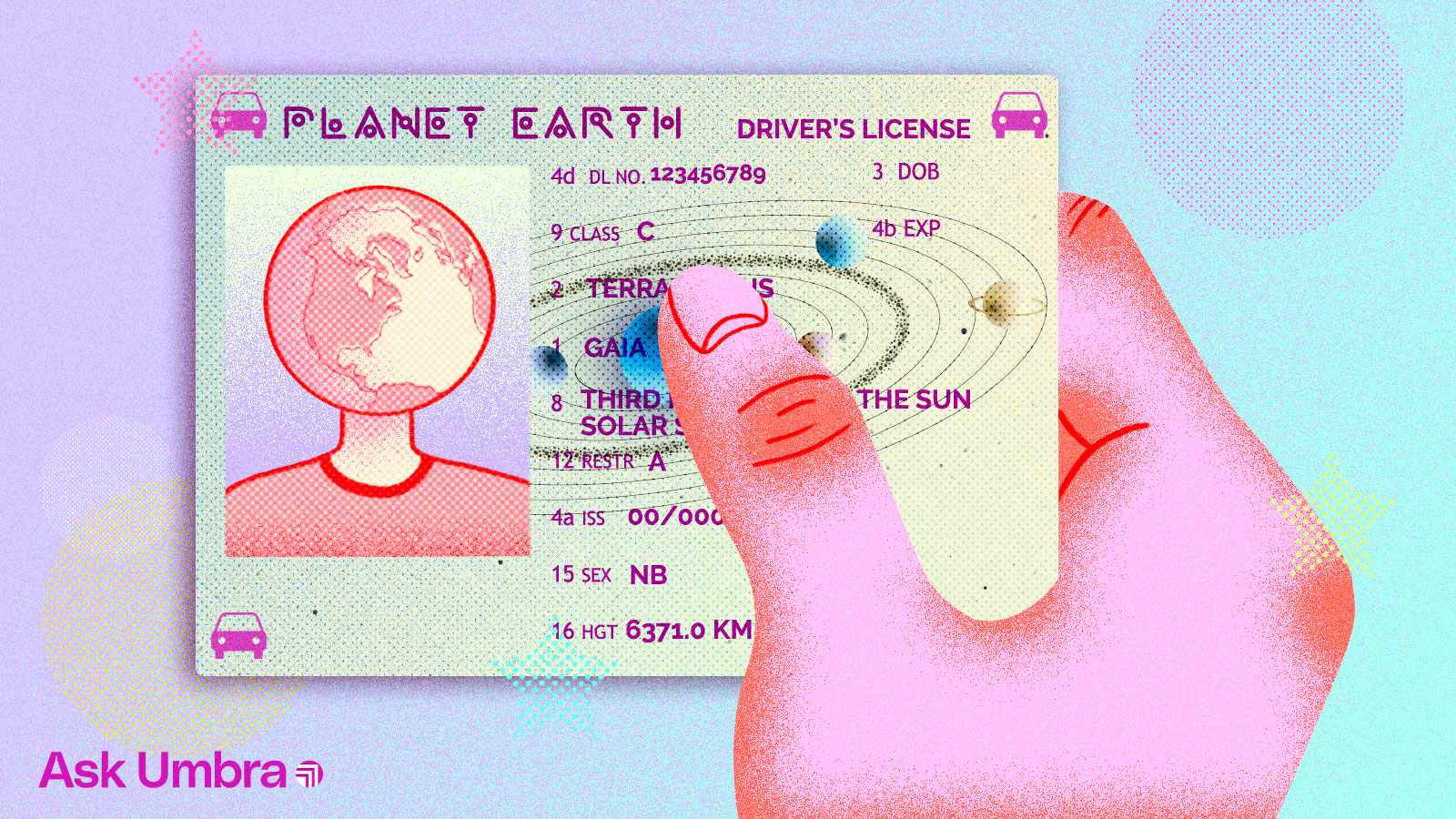

— Can A Reluctant Learner Escape Smoggy System

Dear CARLESS,

I sincerely admire the lengths you’ve gone to to reduce your transportation-related carbon footprint. Lugging home furniture on a bus? I hope, for your sake, that you’re talking about a couple of dining chairs and not, like, a sectional sofa.

It is worth acknowledging for readers that the ability to opt out of car ownership is pretty unusual in modern America. Since the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 created the interstate highway system, enabling the development of sprawling cities and suburbs (and wrecking many thriving Black neighborhoods along the way), most Americans have had no choice but to live in areas where it is difficult to get by without driving.

Many communities are literally designed for cars: Walking and biking are relegated to recreational activities, and public transit is either nonexistent or so under-funded that figuring out how to use it as your main source of transportation is basically a full-time job. It usually takes some combination of intentionality, luck, and resources to build a life in a place with robust enough bus, subway, cycling, and pedestrian infrastructure to sustain a car-free life. I am fortunate enough to have done just that — though I learned to drive when I was 16, I’ve never owned a car because I’ve lived in New York City my entire adult life.

It’s unfortunate that cars are ubiquitous, since they take such a high toll on human health and wellbeing. Transportation is the biggest source of carbon emissions by sector, and light-duty vehicles — also known as passenger cars and trucks — produce a whopping 58 percent of those emissions. Cars spew particulate matter and other forms of pollution that can sicken people who live next to highways. No surprise, those people tend to belong to low-income communities of color. Car crashes also directly kill some 40,000 Americans a year, and an increasing number of those deaths are made up of pedestrians and cyclists. That is partially the result of car manufacturers’ sociopathic arms race to build bigger, heavier cars with higher, more lethal grilles that impede drivers’ visibility.

Even if you can avoid being squished or suffocated by cars and their byproducts, they are still really annoying to be around. Cars can be obnoxiously noisy. They take up countless square miles of valuable public space that could be devoted to affordable housing, express bus lanes, pedestrian and biking paths, green space, outdoor seating, art, performance space, or any number of other more valuable purposes. They’re expensive to own, insure, and maintain, and they force us to spend much of our days alone, isolated from our neighbors and cut off from our larger communities. It’s enough to drive anyone bonkers!

Given all the downsides of cars, you might expect me to advise you to continue living your smaller, simpler, slower car-free lifestyle. But it actually sounds like you — and potentially the planet — have a lot to gain from the mobility and independence that driving would afford you. I think you should get your license, get that large dog, and get your PhD — and look for opportunities to build a world where it’s easier for everyone to live without cars.

I asked Doug Gordon, one of the cohosts of The War on Cars — a cheekily named podcast about the dangers of car dependency — if he thinks adults should learn how to drive if they’ve managed to get by without a car so far in life. He very politely punted. “We think institutional change is where things need to happen,” he said, adding that he’d never tell an individual whether they should drive or not drive. “That person has to do what’s right for their situation.” (For the record: Gordon doesn’t own a car but drives occasionally when his family goes to visit his grandmother.)

In your situation, CARLESS, it’s pretty clear to me that the contributions you can make to addressing climate change by pursuing a degree related to climate mitigation are so much greater than the contributions you can make by refusing to drive under any circumstances. I like your idea of calling local driving schools to ask them to add EVs to their fleet. Even though electric vehicles rely on the same wasteful infrastructure as gasoline-burning cars, they are irrefutably better for the climate. They also produce less pollution and noise. Depending on where you live, you might find the local driving schools are already electrifying their fleet: There are driving schools boasting electric or hybrid vehicles in Florida and California, and the president of the Driving School Association of the Americas told the Guardian last fall that he expected the trend to continue.

Even if you can’t find an EV to learn in, you have other choices available to you that could minimize both the emissions and the other externalities of driving. “If you have the ability and option to learn to drive an electric car, that’s going to be much better for everybody,” Gordon said. “If you have the ability and option to do it in a smaller car and not some mammoth SUV that is more dangerous to everybody outside of the car, that’s also something that you should do.”

To be clear, even though I think you should get your license, I am not advising you to buy a car, and I want to push back against your assumption that learning how to drive makes it more likely that you’ll own a car. Not every choice is a slippery slope, and your agency and moral compass won’t go out the window the second you get your driver’s license. If you’ve gotten this far in life without owning a car, I have a great deal of faith in your ability to continue not owning a car.

You could, for instance, continue taking public transportation for most everyday trips but rent or borrow a car when you need to do fieldwork or take your large dog to the vet. Different car rental and car sharing companies like Zipcar have different pet policies, and many of them require that dogs be kept in crates during trips, so you’ll likely need to do a bit of research to figure out which rental company (and dog) is right for you. You could also think about getting a dog trailer for your bicycle for shorter trips, if you’re confident navigating the bike lanes in your area with a furry friend in tow.

Even if you do wind up buying or leasing a car, perhaps because you’ll need to move to a sprawling part of the country to do your fieldwork, or maybe just because you find that it makes your life significantly easier, that won’t automatically put you on the road to climate ruin. “Just don’t be the kind of person who makes it harder for other people to not own a car,” Gordon said. “Don’t be the person who opposes bike lanes on your street; don’t be the person who complains if a bus lane goes in.”

Get involved in local groups fighting for more bike lanes and public transit options; call and write letters to your mayor and city councilmember telling them you want better alternatives to driving in your area. It’s possible to live within the limitations of the world as it exists today — which for most people means driving — while simultaneously fighting for a better world.

I can tell from your question that you have spent a lot of time thinking about your personal impact on the planet. It can be so tempting, in our individualistic society, to pursue self-purification as a misguided form of climate action — to think that by minimizing our driving, flying, heat and power usage, and meat consumption, we can rid ourselves of the moral burden of contributing to climate change. But climate change won’t be solved by hundreds of millions of people being conscientious consumers. It will be solved by hundreds of millions of people forcing the government and other institutions to dismantle fossil fuel infrastructure and replace it with cleaner, more equitably distributed alternatives.

It sounds like making a small concession to fossil-fuel infrastructure now — by learning how to drive — would give you the ability to contribute to this larger, much more essential project of reshaping society for the better.

Don’t lose sight of the bigger picture, and please give your future dog a pat on the head for me.

Calling shotgun,

Umbra