It’s easy enough to find the dump in Tirana, the fast-growing capital of Albania: just follow the trail of noxious smoke.

For 11 years, this city of 700,000 has been dumping its waste in a suburban field five miles southwest of the center, forming great hills of rotting food, plastics, batteries, appliances, medical waste, and construction materials. Fires smolder throughout the dump, and more are set all the time by the 20 families who live here, eking out a precarious living by collecting metals and other valuables left in the ashes. The resultant clouds of smoke — laden with dioxins and heavy metals — drift over the surrounding neighborhoods, where many parents no longer allow their children to play outside.

One of the poorest countries in Europe, Albania is confronting an environmental crisis that goes well beyond the capital’s garbage woes. While many of its Eastern European neighbors spent the past decade and a half rebuilding from communism, this beleaguered nation staggered from one social upheaval to the next. Now that the dust has settled, Albanian environmental experts are taking stock of the situation and trying to get the attention of foreign donors, whose support will be essential for getting anything done. And getting things done is a requirement; as the country works to join the European Union, it must meet a set of strict environmental standards.

Narin Panariti, legislative and policy director at the Albanian Ministry of the Environment, says the staff there is busy identifying legal and regulatory changes that need to be made to conform with European Union law, a project the office hopes to have completed by the end of the year. “It’s an enormous list of things to do, more than in any other sector except agriculture,” she notes. “It will take us years, probably more than a decade, to perform all the changes.”

Albania, just east of Italy’s boot heel.

Image: Central Intelligence Agency’s

World Factbook.

A Long, Unwinding Road

Long after the collapse of communism, Albania’s 3.5 million people still don’t have a single wastewater treatment plant, toxic-waste disposal facility, or sanitary landfill. The country is littered with abandoned communist-era industrial enterprises that are now home to families of squatters and their livestock, even though the soil, water, and building surfaces are poisoned with contaminants. Peasants are cutting down forests to heat their homes, while construction companies haphazardly mine gravel from riverbeds, disrupting aquatic life and furthering an already critical nationwide erosion problem.

The entire industrial sector collapsed shortly after Albania emerged from communism in the early 1990s, triggering an exodus of 300,000 people to Italy and Greece. Hundreds of thousands more streamed into urban areas from impoverished mountain regions, building homes in city parks, suburban fields, coastal beaches, and the newly abandoned factories. In 1997, the country descended into anarchy following the collapse of fraudulent pyramid investment schemes; by the time order was restored months later, 1,500 were dead, and hundreds of public buildings had been destroyed. Shortly thereafter, nearly half a million Albanian-speaking refugees poured into the country, fleeing the war in neighboring Kosovo.

“The environment has not been, and could not have been, a priority for the government,” says Dhimiter Haxhimihali, a chemist at the University of Tirana and coauthor of several studies on the country’s environmental conditions. Even now, when environmental problems have reached a crisis point, public officials are often unwilling or unable to respond. “There are so many social and economic problems in this country, and the state budget does not have the resources to deal with them,” Haxhimihali says.

Take the situation at the old Porto Romano chemical factory on the outskirts of Durres, Albania’s second-largest city and primary shipping port. Five years ago, delegates from the U.N. Environment Program visited the abandoned pesticide plant and realized they had stumbled upon one of the most contaminated spots in the Balkans. Hundreds of tons of dangerous chemicals had been left in unlocked storage sheds, and others had been dumped in a wetland near the site, which is now in the midst of a residential neighborhood. Area soils contained residues of the pesticide lindane at concentrations of 1,290 to 3,140 milligrams per kilogram of soil; in the Netherlands, authorities intervene when lindane residues reach just 2 mg per kilo. The delegation also found chromium residues, and, in one sample, a level of chlorobenzene 4,000 times higher than E.U. standards.

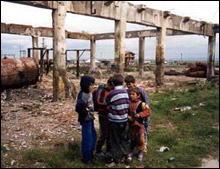

Children play on the contaminated

grounds of the Porto Romano factory.

Photo: GRID-Arendal.

But what really horrified the UNEP team was that thousands of people were living within the contaminated zone, most of them new arrivals from the impoverished north. They had built homes out of materials scavenged from the plant’s buildings, set their cows and sheep out to graze amongst the toxins, even let their children use the factory as a playground. Several families were actually living inside the plant buildings. UNEP called for the plant to be sealed off from the surrounding neighborhood and for an emergency evacuation of the people in the area. The plant, along with four other “hotspots,” posed “immediate risks to human health and the environment” and required “urgent remedial action,” UNEP warned in a prominent report.

Two years later, this reporter visited the site, and nothing had changed. The factory had no fence around it, no signs warding off the children happily playing in the dirt or the owners of the milk cows chomping away on the scraggly vegetation. Mounds of fluorescent yellow waste could be seen scattered alongside the road, in alleyways, and in what appeared to be a schoolyard. Asked about the situation, the mayor of Durres, Miri Hoti, said he lacked the funds to erect a fence and, in any case, was upset that the squatters were making it difficult to sell the plant to private investors. A similar scenario had unfolded at a shuttered PVC plant in the southern city of Vlora.

Now, three years later, the plants have been fenced off, but cleanup work has yet to begin. “The projects depend on the financial capabilities of the ministry, which are quite low since these are incredibly expensive interventions,” says Panariti, noting that the World Bank and the U.N. have funded feasibility studies at the sites. “Without foreign help, there is little we can do.”

Life in the Slow Lane

Even as they’re mired in problems of the past, state and local officials are having difficulty keeping ahead of new affronts. Poorly planned construction projects have marred some of Albania’s most popular beaches and seaside retreats, while new suburban buildings are often not even connected to sewer lines. “Politicians here are very uneasy about complying with land-use strategies or enforcing building laws, because they don’t want to offend people and lose their votes,” says Arian Gace, an Albanian official at the local office of the U.N.’s Global Environment Facility.

Pollution chokes the streets of Tirana.

Photo: GRID-Arendal.

Then there’s the question of air pollution. Under communism, private automobile ownership was illegal; today, upwards of 300,000 vehicles choke the capital’s streets, driving rush-hour dust and small-particle pollution levels to 10 times the World Health Organization safety limit. “Most cars are secondhand and use a very bad quality of diesel,” notes Mihallaq Qirjo, director of the Albania office of the Regional Environmental Center for Central and Eastern Europe. “Albania has exchanged the industrial pollution of the past for the automotive pollution of the present.”

“There is a serious lack of leaders with long-term thinking,” says Gace. “A lot of people just want to get rich, trash the country, and get out. The biggest guarantee I see for environmental improvement is the political pressure exerted by the E.U. to improve enforcement.” The E.U.’s requirement that all applicants meet approved guidelines — which address issues ranging from noise pollution to sustainable development to eco-labeling — might mean the country has to come up with hundreds of millions of dollars to build wastewater-treatment plants and landfills, eliminate leaded fuel, and prevent building in wetlands and other threatened habitats. Gace notes that anything that betters Albania’s prospects for membership is extremely popular with voters. However, it’s not always popular with politicians, who he says tend to have business interests of their own.

“The present politicians do not have a genuine interest in going in the fast lane toward Europe, because if you are going there you must comply with a lot of regulations that are going to lower your profit margins,” he says. Progress, Gace predicts, will likely remain slow.

Even good leadership only goes so far. Edi Rama, the popular and effective mayor of Tirana, has won awards from World Mayor and the U.N. for fighting poverty and corruption. He has knocked down hundreds of shops, discos, and restaurants that had been illegally constructed in the city’s parks, and gotten trash collected and centralized, instead of burning in heaps scattered throughout the city. But Tirana has tripled its size since 1992, creating new problems faster than the municipal government can solve them.

Rama, a former painter, says solving the problems requires coordinated action between his office, parliament, and a variety of government agencies. “Unfortunately,” he says, “getting institutions to work with one another [in this country] is the hardest work you can imagine.”