Q. Dear Umbra,

It seems like there have been a bunch of news stories out lately about “extreme environmentalists” who are pro-planet but anti-immigration. Worse, some are even promoting violence. Where does this ideology come from? How do we stop it?

— Has Everyone Lost the Point?

A. Dear HELP,

I wish I could say environmentalism were as simple as saving trees and picking up trash while jogging, but it tends to veer in a pretty misanthropic direction as soon as we start talking about humans as the root cause of all our current climate woes. Specifically, things get dark when people start debating which humans are most to blame for environmental degradation on a national level.

First of all, it’s true: Human activities are directly responsible for many horrific crimes against nature. Endangered species aren’t choosing to engage in mass suicide, trees don’t burst into flames because they want to, and waterways don’t poison themselves. You can point to any ecosystem that’s fallen apart and tie it back to something that humans have done. Climate change is, of course, the big one: Industrial production of more or less everything depends on the burning of fossil fuels, which in turn ends up warming the atmosphere.

And nothing ramps up industrial production like, well, more humans.

For those with a surface-level understanding of human population growth, this can make groups of people with higher birth rates (such as those in developing countries) easy targets for climate scolding. In the U.S., that ire has largely been directed at more recent immigrants and their descendants, who, according to the Pew Research Center, are projected to account for 88 percent of U.S. population growth through 2065. Is it a coincidence that these scapegoats are mostly nonwhite? Well, what do you think?

Never mind the fact that the strongest indicator of a person’s consumption — and their carbon footprint — is wealth. The reason you don’t see anyone calling to keep out the billionaires is that demographic changes also stoke a protectionist fear: that a rich country needs to protect its supposedly threatened resources from those perceived to be needy newcomers.

Not surprisingly, racism, sexism, classism, and ableism have long fed into the history of the environmental “population control” movement. And tragically, some people have taken this kind of thinking to even more destructive extremes.

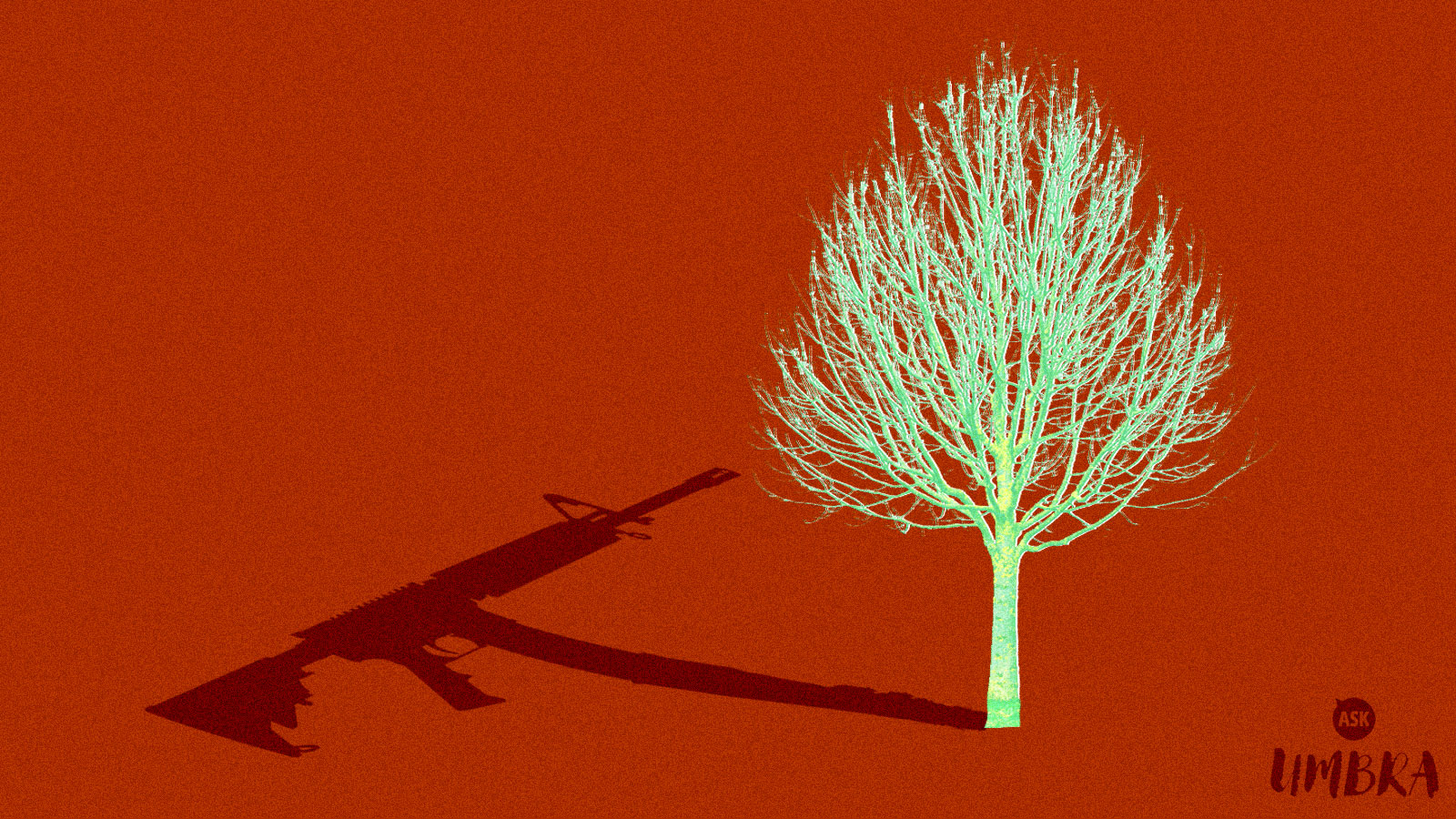

‘Eco-fascism’ is big news, but makes zero sense

I think, when you wrote this question, you may have been referencing this year’s coverage of the Christchurch and El Paso shooters, who together killed 73 people in a mosque, Islamic community center, and shopping mall. Each of them issued a “manifesto” decrying the destructive impact that the proliferation of nonwhite immigrants has had on the natural world. They claimed a responsibility to address this issue, citing that as a rationalization for their blood sprees.

These men were murderers — and, according to some news outlets, “eco-fascists.” It’s a term that refers to the use of fascist means (subjugation, violence, misinformation) to achieve ecological goals (conservation, climate action). Eco-fascists tend to be informed by neo-Malthusian thought, which is basically the idea that the environment is falling apart simply because there are too many people on Earth.

It should go without saying, but killing people to save the planet is not an effective strategy. In fact, it’s not a strategy at all: It’s a farce to cover up bloodlust, a cry for attention, or both. “People with murderous rage will use just about anything to dress it up as something else,” said Lise Van Susteren, a trained forensic psychologist with a focus on climate psychology.

Lawrence Buell, a literary historian and pioneer of the environmental criticism movement agrees. “If I understand these cases correctly, they have to do with ethnic and racial other-ing rather than anything that involves the environment substantively,” he said. The neo-Malthusian argument is “simply a way of adding juice to racist and ethnocentric rage.”

Van Susteren says the kind of simplistic, us-versus-them ideology that typifies fascism appeals to people who are fearful and anxious. “We regress when we’re fearful,” she said, whether that manifests as clinging to “strong” leaders with extremist views or expressing our vulnerability through anger at selective scapegoats.

And dumping poison into the terrible soup that is Americans’ political views on climate action is decidedly not helpful. The dangers associated with global warming are hardly limited to wet feet. When something as fundamental as planetary physics transforms, it can undo the basic functioning of society. The sense of that loss of control, to put it simply, drives people nuts. Climate change is deeply, existentially frightening, to the point where it can shut down what could be considered normal human psychological functioning.

But even if you theoretically felt so desperate about the state of environmental collapse, so afraid of threats to food or water or wealth, it still wouldn’t make any sense to attack those who, just like you, have little to no control over it.

So-called eco-fascists aren’t trying to challenge the power structures that created climate change in any meaningful way; they’re simply trying to lash out at those more vulnerable than them. “If we just think about this through a psychological lens, it’s easier to attack those groups that are being positioned as very ‘other’ than it is those closer to the world in which [the attacker] may associate or benefit or relate to,” says Renee Lertzman, a social climate psychologist. “There’s something about calling out actual power that must seem unattainable or too threatening. It brings up too much cognitive dissonance.”

And unfortunately, it’s not the misnomered “lone wolves” using fear as a tool to divide and discriminate against the perceived “other.”

The less murder-y, equally racist history of the environmental movement

They may not have directly killed anyone, but many prominent (read: white) influencers of ecological thought have also espoused ideas about population/resource control that are focused on limiting the numbers of certain groups of people more than others.

Let’s start by unraveling the teachings of famed conservationist and more-than-a-little racist environmental figure Aldo Leopold. Leopold correctly noted that unregulated economic growth and industry would decimate ecosystems, and he devoted his career to addressing that conflict. But at the same time, he fretted over the influx of Asian and other foreign immigrants to the United States, fearmongering to his colleagues about how these new arrivals would “overrun the country.”

It would be difficult to argue that these immigrants were the drivers or even the primary beneficiaries of the ecology-ruining industry that Leopold worked against. But like many early published environmental thinkers, he was operating off the assumption that some humans had a greater right to enjoy the beauty of nature than others. In After Nature: A Politics for the Anthropocene, Jedediah Purdy wrote that early conservationist thought leaders, like eugenicist Madison Grant, “assumed that certain types of Americans were specially tied to, and qualified to interpret and advocate for, the natural world.” Not surprisingly, those chosen few were assumed to be the white, rich, and highly educated.

There may be no better modern example of this warped, exceptionalist brand of “environmentalism” than the heiress Cordelia Scaife May, famous lover of nature and wildlife and fanatical racist who campaigned against immigrants until her death. Her wealth came from the massive Mellon fortune — the product of banking, steel production, and oil development starting in the 19th century. It’s painfully ironic that Pittsburgh, my hometown, birthed both Scaife May and Rachel Carson, the acclaimed environmentalist and author of the landmark book Silent Spring. Unlike Carson, whose work was used to fight for major environmental reform, Scaife May’s legacy is deeply tied to today’s xenophobic political landscape.

Scaife May’s Pittsburgh-based Colcom Foundation funds both conservation efforts and anti-immigrant groups. In fact, over the years, Colcom has spent twice the amount of money supporting anti-immigrant groups, like the misleadingly named Center for Immigration Studies, as it has on straight conservation efforts. The message of Scaife May’s foundation seems to be that immigrants are “ruining” the country by befouling pristine habitats, and squeezing limited resources.

It’s not a killer’s manifesto, but the ideological similarities are undeniable.

One could easily argue that Scaife May’s own family, being directly responsible for a significant percentage of coal and oil extraction at the peak of the industrial era, bears a far greater share of the responsibility for climate change and environmental degradation than any of the people that she sought to keep out of the country. But self-awareness is not many people’s strong suit in the face of overwhelming, existential fear, especially when those false convictions are validated by those in positions of power.

Fighting against fear

So now that we know people lash out at those who have less power than they do when faced with our planet’s existential crisis, what can we do about it? To start, try to emphasize that climate catastrophe is not yet a done deal. As I’ve argued before, why jump immediately to dealing with climate change by getting rid of humans when there are still so many other options? It makes no sense. It’s like cutting off your hand because you broke your wrist.

But neither can we afford to completely ignore these fringe thinkers. I foolishly used to assume that hateful misanthropes were not my problem, but in October of last year, one of those angry people murdered 11 people in the synagogue where my family worships. That attack, too, was driven by a hatred or fear of people who did not look or pray like the shooter. In the current climate of mass shootings and availability of assault rifles, I do believe it’s only a matter of time before a random stranger’s rage becomes your personal problem if it hasn’t already.

So, do what you can to ensure that angry people can’t get access to assault weapons. That part, at least, is very simple. And then, call those attacks out for what they are: As empty of any grander purpose as they are of hope.

Optimistically,

Umbra