Slim pine trunks stacked in a mound loomed over my head, curving around me in a partial circle like a dam built by Brontosaurus-sized beavers. I’d followed a long unmarked dirt road earlier this year to see it: One of 48 wood piles in a 12 square-mile section of the Tahoe National Forest outside the town of Truckee in northern California. You can find similar scenes across the western United States, anywhere work crews are clearing brush and small trees from forests.

They’re monuments to a widespread effort to cull tinder for future wildfires. Drought, disease, and insects have left 100 million dead trees browning across California, and in some places, 90 percent of the trees have died. All this dry wood can stoke small blazes into uncontrollable infernos that ravage towns and choke the region with smoke. Last year was California’s worst fire season yet, with blazes blackening an area the size of Delaware and killing 104 people. Forests are so unhealthy they are now emitting more carbon than they produce, according to recent studies.

At the same time, California is counting on its forests sucking up lots of carbon from cars, factories, and power plants to meet its goals to slash carbon emissions. If forests are greenhouse-gas emitters rather than sinks, it puts a massive hole in those plans.

Those giant piles of wood were just a tiny part of a massive outlay of money and sweat to restore forests in California and across the West. The state has removed 1.5 million dead trees in the last three years, said Nic Enstice, a scientist at the Sierra Nevada Conservancy, a California state agency. “But we’re not keeping pace,” he said. “There are way more dead trees out there than we will ever get to.”

When settlers took control of what would become the western United States in the 1800s, they started putting out the fires, reversing the Native American practice of setting fires to manage forests. After nearly two centuries of fire suppression, the forests have changed. Shade-tolerant species like incense cedar and white fir have crowded under the pines, Enstice said. Once spacious groves are now choked with small trees and brush. And when drought hits California, exacerbated by ever-hotter summers, these trees have to compete for scarce water. As they dry up, the pines are unable to produce the sap needed to fend off bark beetles, which girdle one tree after another, turning big patches of forest canopy from green to a sickly reddish-brown.

The 15-foot towers of kindling that I saw aren’t even the largest, said Steve Frisch, president of the Sierra Business Council, a nonprofit that works to improve the region surrounding the Sierra Nevada mountains. “I’ve seen these piles when I’m out mountain biking,” he said. “I come around a corner and all of a sudden there’s this freaking massive mound of wood the size of a four-story apartment building.”

It’s so difficult and expensive to haul these mounds out of the forests that workers often end up dousing them with lighter fluid and setting them ablaze. Better to release the heat and pollution during the winter, they figure, rather than in the summer as part of a wildfire. But either way, the result is more carbon emissions.

The situation has led some environmentalists to a counterintuitive idea: turning that wood into energy. When wood burns in power plants, the smoke passes through a series of filters so that the plume that drifts up from the smokestack has almost none of the harmful particulates that would be released if it burned in a wildfire or bonfire. It’s a way to reduce pollution and generate energy at the same time. Advocates imagine small wood-burning plants scattered throughout the West, providing power to mountain towns and providing an economic incentive to keep clearing excess wood, shrink forest fires, and allow the remaining trees to grow stronger and healthier.

These wood-fired plants produce what’s known as biomass energy. Biomass is just the general term for grass, dung, corn, or anything else containing energy (soaked up from sunlight) stored in chains of carbon (soaked up from the air). By burning biomass, you release the sun’s energy in the form of heat and light. But you also release its carbon back into the atmosphere.

That’s one of the reasons it’s controversial as hell. Environmentalists have long fought to block biomass power plants. Turning trees into electricity seems to violate the basic tenets of tree hugging. There’s a thorny debate over whether biomass energy can really be considered clean or renewable. But there’s no doubt that biomass plants can be environmental disasters when run improperly. After all, producing electricity by burning wood produces more carbon and pollution per kilowatt than burning coal, the Sierra Club points out. The group’s California branch recently plastered billboards with the anti-biomass message, “A tree is a great life source, not an energy source.” Which makes the fact that some deep-green activists are campaigning to build wood-burning power plants in their own backyards all the more surprising.

Jim Turner, who runs a biomass plant, stands in front of a pile of wood in the Tahoe National Forest. Photo by Nathanael Johnson

Barbara and Don Rivenes fell in love with the West Coast’s wilderness after moving to California in 1967 with their young family. “I just couldn’t get over the landscape,” Barbara said. “California knocked my socks off.”

They became avid environmentalists, volunteering and attending countless meetings. Barbara was the sole employee for the Golden Gate Audubon Society and Don served on the state board — “and every other damn thing,” Barbara said. In 1997, the Rivenes moved to Nevada City, a town enveloped by a green mantle of ponderosa pines in the foothills of the Sierra Nevadas between Sacramento and Lake Tahoe. They dove into the work of protecting the forest. Barbara got involved with the local Sierra Club chapter, and Don became executive director of the Forest Issues Group — a watchdog organization that tries to stop companies from logging and destroying habitat.

When government officials and fire experts formed a group to figure out what to do with all the wood stacking up in the surrounding forests — a biomass task force — Barbara and Don seemed like perfect candidates to represent the environmentalist’s perspective.

In 2010, they attended their first of many task-force meetings in a packed government building. Bureaucrats, politicians, and fire experts from universities floated proposals for taking care of the wood. The timber was too small to turn into traditional lumber, but it could serve as dandy fence posts or maybe woodchips for a playground. None of the suggestions would’ve put a dent in the massive supply. More promising was the idea of using wood for the construction of tall buildings instead of concrete and steel, which together produce about 10 percent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. That would sequester the carbon small trees had absorbed during their lives. But current building codes make it hard to build very tall wood structures. In the meantime, the experts concluded, the cost of trucking the wood out of the forest would exceed the amount anyone would pay. So the stacks stayed put.

As the meetings piled up, Don and Barbara gradually became convinced that biomass energy plants could help the Western United States manage its forests. Though they still opposed cutting down trees just to burn them, they reasoned that it would be better to burn trees in biomass plants than to burn those house-sized mounds where they stood. Burning wood efficiently in biomass furnaces and running the smoke through filters would eliminate most of the particulate pollution, including 98 percent of the soot — sometimes called the second most important heat-trapping pollutant after carbon dioxide.

The Nevada County task force — Barbara and Don included — launched a study that found that the ongoing work of thinning dense trees from the surrounding forests would generate nearly five times as much wood as a 3-megawatt plant (providing enough energy to power 3,000 homes) could use every year. That relieved the Rivenes’ concern that a biomass plant could lead to deforestation. “It seemed like there are good possibilities for this, if you are careful,” Barbara said.

Steve Eubanks, with Barbara and Don Rivenes, on the site selected for a biomass plant in Grass Valley, California. Photo by Nathanael Johnson

The notion of peppering California’s rural mountain towns with small wood-burning power plants might have sounded improbable when this local group started meeting. But then California’s legislature passed a law to subsidize small biomass plants in 2012. The idea behind the legislation was that plants would spring up to provide power to small towns, providing an economic incentive to clear fuels out of the path of future wildfires. A private company expressed interest in building a plant in Grass Valley, next door to Nevada City, if it could work out a deal to sell the power it generated to California’s primary utility company, Pacific Gas & Electric.

Locals seemed to like the idea, which sounds incredible to anyone familiar with area. In the 1960s, the region became a popular refuge for hippies and artists from the Bay Area — folks who usually embrace nature and fight to shut down logging operations. “In Nevada City, if there was someone standing on the corner handing out $100 bills, there would be people protesting,” said Steve Eubanks, the former supervisor of the Tahoe National Forest and a member of that biomass task force. “But there hasn’t been serious opposition to this.”

The plant might already be under construction were it not for a twist of fate. The company behind the proposed Grass Valley biomass plant couldn’t negotiate a deal to sell power to PG&E because the utility declared bankruptcy in January. The main reason it filed for Chapter 11 protection: massive liability claims from wildfires. In an irony that crops up routinely in our warming world, efforts to adapt to a rapidly changing environment were thwarted by a rapidly changing environment.

Traditionally, environmentalists have fought to stop chainsaws and bulldozers, so it’s no surprise that most oppose logging for biomass energy. Outfits like the Natural Resource Defense Council, for instance, have been campaigning against the practice of clearcutting forests in Southeastern states to make wood pellets for export to biomass plants in Europe. Although small, California-style biomass plants have drawn support from some major environmental groups, others, like the Center for Biological Diversity and the John Muir Project, remain adamantly opposed. Part of the reason is that the opposition to burning anything for energy that releases carbon into the air runs deep.

“Treating the trees in our forests like they are sticks of coal is one of the biggest threats to climate change mitigation that’s out there right now,” said Chad Hanson, a forest ecologist who directs the John Muir Project.

In the Western states, the fight over biomass isn’t just about the best ways to create energy; it’s also a dispute over how to manage forests. Some groups argue for prescribed burns and selective cutting to restore forests to something closer to how they were before settlers started clearcutting and suppressing fire.

But according to Hanson, the conventional wisdom that California’s forests are unhealthily dense with wildfire fuel and need to be cleaned up is just wrong. He rejects the idea that thinning forests — and creating the fuel for biomass plants along the way — makes wildfires any less destructive.

Instead of a build-up of needles and branches, Hanson sees a build-up of carbon. It seems crazy, from his perspective, to burn this wood before a wildfire gets to it and release all that carbon into the air. Better to spend money on fireproofing houses and let the forests burn and recover as they may, Hanson said. “That’s one of the key aspects of the dominant narrative: You’ve got to go thin the forest — no, no, you don’t,” he said. “Biomass logging does not prevent fires. The more you do it, the more likely the fires are going to burn hotter, and faster, and more intensely.”

In a review of scientific studies on forest carbon management, two professors at Oregon State University, Beverly Law and Mark Harmon, made the case that cutting small trees to reduce carbon emissions from wildfires simply doesn’t work because you end up having to remove more wood than those fires would burn — leaving fewer trees to store carbon.

Even if you embrace Hanson’s position that a hands-off approach is best, utilities and municipal workers in California continue cutting down trees to protect themselves from fire. Homeowners are supposed to clear a “defensible space” 100 feet from their houses. All that work is generating tons of woody biomass. I asked Kathryn Phillips, who leads the lobbying efforts for Sierra Club California, if she thought it made sense to burn that wood to generate energy.

Though Phillips’ organization is officially neutral on the point, her response was that people shouldn’t be burning wood at all. The best option is to leave the wood in the forest. The rest might be chipped up or used for furniture and building materials. If people need to clear fuels off their land, “they need to figure out options to do something with that wood,” she said. “And if those options don’t exist they need to complain to the state. Burning it in a biomass plant isn’t the answer.”

Almost all of the researchers I talked to thought that forest would be healthier with some thinning and burning to repair the legacy of clearcutting and fire suppression. Researchers were split, however, on the question of whether managing forests, or leaving them to the whims of nature, would allow them to soak up more carbon from the atmosphere. I began to notice a pattern: Scientists based in Oregon and Washington would tell me that simply leaving forests be was the best way to catch carbon, while researchers in Arizona and California would stress the importance of cutting some trees and performing prescribed burns. It makes sense: Forests get a lot more flammable as you move south. In the more arid parts of the West, they’re adapted to fires passing through as often as every five years, but a century of fire suppression has left them starved for burns.

The differing views even show up in the models researchers build to forecast how forests will respond to management. If you assume forests will rarely burn, as they did in the era of fire suppression, your models will show that it’s better to let nature take its course, said Dick Cameron, director of terrestrial science for The Nature Conservancy. In short, whether thinning and controlled burns can help trees suck up more carbon likely depends on the changing climate, Cameron said.

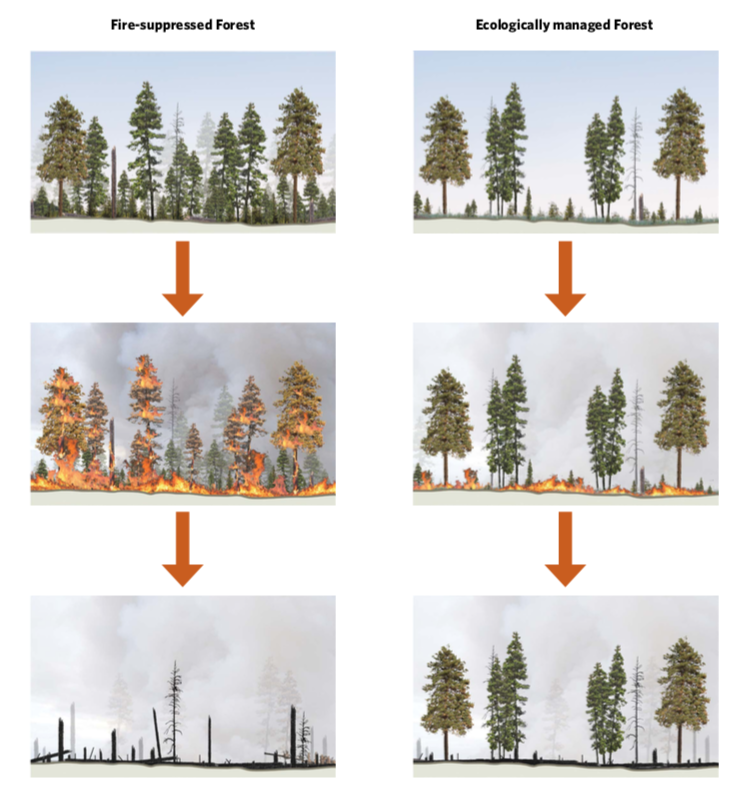

The Nature Conservancy

The Nature Conservancy recently reviewed the science on California’s forests and determined that thinning trees and setting prescribed burns — “active management” — would release more carbon in the beginning but pay off in the long run with big, carbon-gulping trees that can survive forest fires.

That jibes with what the many scientists I talked to told me. Trees in dense thickets compete for water, said Matthew Hurteau, a scientist at the University of New Mexico who studies the way forests adapt to climate change. When researchers remove small trees, he said, the remaining larger trees grew rapidly, sucking up more carbon and storing it in thicker rings of wood than previous years

For the Nature Conservancy, it isn’t just a question of carbon. The organization is also interested in improving wildlife habitat, safeguarding clean water supplies, and protecting people from the harmful effects of wildfire smoke. “There are a lot of reasons we really see a need to actively manage these forests,” Cameron said. Actively managing even a small percentage of California’s forest land would generate many more giant piles of wood that might go to biomass plants.

Although Nevada City wasn’t able to work out a deal with PG&E, other biomass projects are getting underway in mountain towns across northern California as residents come to the same realization as Rivenes’ task force. The town of Quincy built a biomass furnace last year to supply heat and power to government buildings. In the foothills east of Fresno, the town of North Fork is building another small plant. Both have the support of local environmental nonprofits. In Calaveras County, southeast of Sacramento, one organic farmer has been rallying support to build a biomass generator. In Mariposa County, which includes part of Yosemite National Park, a group of renewable power enthusiasts embraced biomass after they realized that the county couldn’t get off fossil fuels by just relying on solar, wind, and batteries (nobody has figured out how to do that yet without occasionally leaving the town in the dark). The forests in that part of the state are so unhealthy that even the most chainsaw-averse tree hugger might have second thoughts.

“We have people drive up here and say, ‘Why are all your trees dead?’ There are areas that look like they’ve been hit by a bomb,” said Steve Smallcombe, one of the volunteers working to get a small biomass plant in Mariposa. “I think environmentalists see that the way our forests have become isn’t good for anyone.”

Several environmental activists told me that as forests have deteriorated, they’ve seen a shift in the way environmental groups approached biomass plants. They’ve moved from outright opposition to silence, and sometimes have even campaigned on behalf of small plants. The nonprofit Sierra Institute for Community and the Environment, for instance, championed Quincy’s biomass plant.

“It’s always anxiety-producing to support something related to cutting down trees,” said Sue Britting, executive director of the environmental group Sierra Forest Legacy. “But we have certainly been neutral on some biomass plants — and sometimes support them outright.”

This change in environmental attitudes might signal the start of a new stage in the relationship between humans and forests in the West. In the first stage, Native Americans used forests sustainably, frequently setting them on fire to clear out underbrush and improve habitat for game, according to Jonathan Kusel, the Sierra Institute for Community and the Environment’s executive director. In the second stage, starting in the Gold Rush and continuing into the 1950s, when logging peaked in California, Americans levelled forests. “The history of the timber industry is one of cutting across the country, leaving the land bare and moving on,” Kusel said.

In the third stage, environmentalists fought the timber industry and, by the 1990s, they’d effectively won, putting an end to most logging in the state. This victory, Kusel said, went too far, thwarting good forest management and leaving people in many small towns without much work. “Twenty years ago, environmentalists and industry were both saying, ‘We’re fighting on the side of rural communities,’” Kusel said. “They were both lying.” The timber industry just wanted to extract profits and move on, he said — and once environmental groups won in court, they moved on, too.

The fourth stage of this relationship between humans and trees, then, could be a return to sustainable use — in which forests provide wood for people to build houses and maybe some renewable energy.

Those giant piles of wood I saw this spring have been sitting in the forest for years now. Jim Turner, who runs a biomass plant a half hour away in the town of Loyalton, wanted to get his hands on them.

Turner’s plant was once home to a sawmill, and its generator burned scrap wood. Its General Electric steam turbine was manufactured in the 1950s, but mechanics rebuilt it entirely in 2010. Now the machine hums along — producing enough electricity to power 20,000 houses — possessing the weathered beauty of a well-made old tool.

Jim Turner in the American Renewable Power plant in Loyalton, California. Photo by Nathanael Johnson

When the mill closed in 2001, Turner convinced the timber company, Sierra Pacific Industries, to keep the biomass plant going. “It wasn’t some magnanimous thing,” he said. “It just had to be done. I wanted to live here.”

Today, the plant has 21 full time employees from Loyalton’s population of around 700. It’s easy to see why Turner wanted to stay. The plant sits on a beautiful spot, surrounded by a handful of houses clustered in a mountain meadow ringed by wooded peaks. Turner never locks his doors, and he likes that his neighbor feels comfortable enough to borrow his truck sometimes without bothering to ask.

Some environmentalists worry that more small biomass plants like Turner’s would drive deforestation. It’s an objection that’s lost on Turner. He can only afford to pay $30 or $40 for a ton of wood. If someone was going to cut down big trees, they’d sell them to a lumber mill for $200 a ton, maybe more. Data obtained from the Forest Service shows that it would take Turner more than 20 years to use up woodpiles from land within 70 miles of the Loyalton plant where the Forest Service could thin out small trees. After 20 years, those original acres would be due for a second thinning.

These days, fewer environmentalists are claiming that Turner wants to clear cut forests, and more are asking him for help.

“In the 2000s, we were demonized,” Turner said. “Biomass! It’s dirty power. But in 2009 I started to see a huge shift with these catastrophic wildfires.”

Backpackers and mountain bikers in the Western U.S. can no longer mistake their forests for a perfectly balanced garden of Eden. Neither can city dwellers: This summer was the first since 2015 that people weren’t choking on wildfire smoke up and down the West Coast.

For the first time in this Californian’s memory, lots of people are thinking about leaving the state because of the poor air quality. And it’s likely to get worse before it gets better. Estimates suggest that twice as much forest burned in an average year before European settlement as burned in 2018, when more of California burned than any year since 1800. The Western United States is probably going to be a much smokier place as fires consume a century of backlogged fuel — unless forest managers can space out those burns and trap some of the smoke in filters.

Even if biomass power gathers more public support, Turner is skeptical that small plants like the one planned for Nevada City can survive. Without more government help, it would be hard for plants like his to turn a profit. Turner has other troubles: The company American Renewable Power bought his plant in 2017, and since then it has lost money. “I’m just going to lay it out there,” he said. “I’m impressed that the investors have hung on.”

Instead of supporting biomass by forcing utilities to pay extra for the electricity, Turner said it might make more sense for the state to pay directly for the things its citizens want: forest health, smoke reduction, and carbon sequestration. If biomass plants can provide those services, “that’s great” he said. “And if not, if something else is cheaper, fair enough. Let’s not waste taxpayer money.”

Earlier this month, the Forest Service and Turner finally agreed on a price after months of negotiations, and workers began moving that brushy edifice of wood from outside Truckee to the Loyalton plant. Scores of wood piles remain scattered throughout California and the rest of the Western states. Steve Eubanks, who spent 40 years in the Forest Service, said there’s no question about what will happen if the service’s land managers can’t sell that wood: They will simply burn it in place.

*Correction: An earlier version of this story misattributed a quote to Patrick Gonzalez, a forest ecologist at the University of California at Berkeley.