The morning we left camp, the mountains were wreathed in smoke from wildfires burning in Yosemite National Park. The top of the peak, previously visible from camp, was now barely distinguishable in the haze. A light rain seemed to clear the atmosphere slightly and soon we were in clean air, walking through meadows of summer flowers and small streams hidden by the long grass. Sing Peak came into focus.

Located in the southeast corner of Yosemite National Park, Sing Peak draws little attention. It’s a non-descript rocky mass that lacks the sweeping majesty of, say, Half Dome. But Sing Peak holds a rare distinction. The 10,552-foot mountain is named after a Chinese American — Tie Sing, a camp cook for the U.S. Geological Survey from the late 1800s and early 1900s.

The backpacking trip was part of last year’s Sing Peak Pilgrimage, an annual series of events held in July that commemorates Sing and Chinese-American laborers who built the first roads in the national park. The Pilgrimage is a project founded by my dad, Jack Shu, a retired California State Parks superintendent and avid hiker. Long committed to bringing more people of color to parks and outdoors recreation, he started the project, in 2013, as a way to both educate more people about the history of Asian Americans in national parks and diversify Yosemite’s visitors.

The National Parks Service needs the help. According to a 2011 report from the NPS, only 3 percent of visitors to the parks system were Asian and Pacific Islander (Asian Americans make up 5.8 percent of the U.S. population). The lack of Asian Americans on the NPS staff is even more pronounced. According to the Partnership for Public Service, just 2 percent of NPS employees are Asian.

Julia Shu

As Brentin Mock has written, the lack of minorities in America’s national parks is in part due to a history of racism, segregation, and systematic discrimination. For Asian Americans, unique cultural and historical circumstances have led to this absence, and worse, a perception that Asians aren’t present in the outdoors. But turns out Asian Americans have played a significant role in the history of national parks, and the Sing Peak Pilgrimage is tapping this history to help bring more people of all backgrounds to the outdoors.

For Chinese Americans, the history of discrimination goes back to the late 19th century. From 1882 to 1883, Chinese laborers built the main road crossing through Yosemite. But also in 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed, the first explicitly racial discriminatory immigration law in the U.S. The act was part of a rising fever of anti-immigrant racism and violence.

“There was competition for work and jobs, in fact the 1879 California constitution had a clause that prohibited Chinese from working on any public works projects,” explained Eugene Moy, the former head of the Chinese Historical Association of Southern California and one of the organizers of the pilgrimage. (How the Chinese laborers were allowed to work in Yosemite after 1879 isn’t exactly clear; it’s likely the clause in the 1879 California constitution wasn’t enforced.)

Moy said that at one point many Chinese workers lived in rural areas near places like Yosemite, but they didn’t stay long.

“I think a lot of workers either left to go back to China or left to go to the bigger towns where it was a little bit safer,” said Moy, adding, “often times in the outlying areas like this the Chinese encountered a lot of hostility.” For example, in 1885, a mob of angry white workers murdered 28 Chinese miners who had been hired as strike-breakers in Wyoming.

More than a century later, Asian Americans are still largely absent from the wilderness. Katie Wang, a UCLA grad student on the pilgrimage who told me she hadn’t had much camping or hiking experience, admitted that seeing so many Asians together was not what she imagined when thinking about parks.

“Maybe it’s related to model minority stereotypes that Asian Americans are so focused on success, academics, and science,” she said, “and they’re less focused on nature and parks, and less focused on recreation in general.”

Sure, maybe there are some Asian kids who would be happier doing math instead of camping. But the reasons go deeper than homework. A 2010 report from the Outdoor Foundation says that for Asian American youth, parental influence is the highest ranked factor determining whether or not the kids participate in outdoors activities. In other words, people tend to follow family traditions. And for some families, outdoors recreation might not sound like recreation at all. Many Asian Americans descend from immigrant parents or grandparents who worked long hours just to pay for housing and education for their children. Not only does camping or “roughing it” require a certain amount of time, money, and access, it can recall tougher living conditions.

During the Sing Peak Pilgrimage, a Taiwanese-American man told me, while thrashing through some mosquito-infested bushes, that camping just isn’t a very Asian thing to do. “It’s dirty,” he said. “Most Chinese don’t want to vacation sleeping on the ground.” A recent overall boom in Chinese tourism to the U.S. has led to an influx of bused-in visitors to places like Yosemite and Yellowstone, but it’s unclear whether the uptick in international visitors will have any influence on Asian Americans.

This weight of family and cultural perceptions emphasizes the importance of Asian Americans being able to picture themselves in parks, as historical figures and as employees and visitors.

Which brings me to Tie Sing, for whom Sing Peak was named. Sing was a cook employed by the U.S. Geological Survey for various expeditions. Most notably, he cooked for the Mountain Mather Party, a group of influential politicians and businessmen who toured Yosemite and decided to found the NPS.

“Tie Sing was genuinely loved by the people that met him,” said Yenyen Chan, a ranger at Yosemite. “He met so many important people in the national parks history.”

Yenyen Chan, a ranger at YosemiteJulia Shu

Chan is responsible for uncovering and publicizing much of the history of Chinese laborers in the park. In an NPS video about Sing Peak, she quotes the writer Robert Sterling Yard, who attended several of Tie Sing’s famous meals in the wilderness. Wrote Yard: “The extraordinary recitals of his culinary talents had been more than I could quite believe, but I believe them all now and more. I shall not forget that dinner — soup, trout, chops, fried potatoes, string beans, fresh bread, hot apple pie, cheese, and coffee.”

How Sing produced all this food in the backcountry only adds to his legend (one theory suggests he packed bags of bread dough on the sides of mules so the heat of the animals would make the dough rise).

Having been on a backpacking trip with my dad before, I knew better than to expect fresh bread and hot apple pie on last year’s pilgrimage. In fact, I was reluctant to go at first, especially because Sing Peak is not the most photogenic of Yosemite’s sights. But I bowed to parental pressure and signed up. The group of more than 20 hikers included members of the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California, a hiking club of Taiwanese immigrants, and black and Latino teens from East L.A. with the program Outward Bound. Everyone there seemed to understand the rarity of seeing so many non-white hikers.

That smoky morning, as we set off into higher elevations toward Sing Peak, we were rewarded. The wilderness was undeniably beautiful, with tall trees silhouetted against the harsh blue sky and steep rocky hillsides.

When we finally reached the summit, an excited euphoria took over. For the past two years I have lived in New York City, desperately missing the hikes I went on as a kid and the landscapes of California’s coast and mountains. At the top of Sing Peak, reveling in the success of the hike and looking down at Yosemite, I was enormously happy to have come. This is why diversifying parks is important — more than for the sake of history or undiscovered mountains, but because being outdoors in nature is restorative, a luxury too often prohibited but nonetheless essential.

Julia Shu

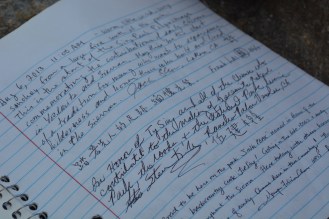

The first year of the pilgrimage, a notebook for hikers to sign had been left in a plastic container, wedged between some rocks on the peak. When we pulled out the notebook on last year’s trip it had signatures from all over California, Florida, Minnesota, even Bogota, Colombia. A creative hiker with a good memory had written down a full passage from The Hobbit. Sing Peak was becoming a historical site that mattered to people, shedding its years of neglect on topography maps. And here again, more than 20 people of color had climbed its trails to enjoy the beauty of the national park Tie Sing helped create.

We passed the notebook around and added a new batch of signatures.

Julia Shu

This year, the Sing Peak Pilgrimage takes place July 24-28. For more information go to the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California website.